CAN ARROWS TRUMP BULLETS?

Bow Vs. Colt: And The Winner Is…

Long after Colonel Colt equipped cavalry — hostile tribes stuck to the bow. Here’s the logic!

In 1865, workers at Remington’s factory in Ilion, N.Y., sat by heavily-mortgaged tooling, the machines silenced by war’s end. To court sportsmen, Remington rushed Joseph Rider’s improvements on the Geiger split-breech mechanism and announced the Rolling Block Rifle.

Simple in design, the Rolling Block was nearly foolproof and so quick to load that a practiced shooter could send 20 shots a minute! It was strong, too. In tests, one rifle was triggered with 750 grains of black powder and 40 balls filling 36″ of its 40″ barrel. Upon firing, “nothing extraordinary occurred.”

The rifle proved itself in 1866 when 30 cowboys led by Nelson Story herded 3,000 cattle through Wyoming. With Rolling Blocks bought at Fort Leavenworth, the men repulsed an Indian attack near Fort Laramie. Beyond Fort Kearney, hordes of hostile Sioux under Red Cloud and Crazy Horse swooped from the hills. The cowboys shot until canteen water sizzled on their barrels. The Sioux expected a pause; none came. Retreating, they stopped to look back — and found the Remingtons had great reach! Story and his cowboys blunted two more Indian attacks. They reached Montana with the loss of just one drover.

The Rolling Block served buffalo hunters who raked in as much as $10,000 a year selling hides. The rifle also gained favor among European heads of state. But in Prussia, amid great pomp, a cartridge failed. The man who would become Kaiser Wilhelm I rode off in a huff. George Custer had better luck. After a hunt in 1873, he reported: “With your rifle I killed far more game than any other single party … at longer range.” Three years later, at the Little Big Horn, Custer’s doomed troops carried Springfields.

Warriors And Rifles?

But warriors who pestered settlers and bloodied the best US cavalry didn’t always out-gun their adversaries. Like Hawken-style plains rifles before them, Rolling Block and dropping-block Sharps rifles were long and heavy, ill-adapted to the high-speed horseback maneuvers that made the plains Indian so fearsome in battle. Besides, they chambered cartridges often hard to find. The only ammo available to the warrior grabbing a .50-90 Sharps might be on its dead owner. As importantly, a bow could be made and repaired with natural materials. Arrows too. Knapping a beautiful obsidian head took patience and hard-earned talent — but arrowheads didn’t have to look good to kill.

Indian opinions of rifles changed as repeaters appeared. The lever-action Henry, spawned by the 1849 Hunt Volitional Repeater, had been tested during the Civil War. During the 1864 Atlanta campaign, a Confederate soldier told his captors: “One of your men [faced us four and fired as we did]. One of our group fell … The rest of us proceeded to load, when he fired twice in quick succession, killing two more of my comrades. At this point, I had my gun loaded and … a cap in my fingers [but] dropped both … Sir, there is no use in the South fighting men armed as yours are armed.”

Still, the Henry sometimes balked, and its 216-gr. .44 Rimfire bullet, driven by 26 grs. of black powder to 1,025 fps, had less punch at the muzzle than does a modern .30-30 bullet at 350 yards!

The Model 1866 that followed was the first rifle by the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. A 28-gr. powder charge gave the 200-gr. bullet a little more pep. But its successor, the Model 1873, had real muscle. Its .44-40 cartridge, Winchester’s first centerfire, hurled a 200-gr. bullet at 1,200 fps. In 1878 Colt cataloged its Single Action Army revolver in .44-40. Packing one type of ammunition working in rifle and revolver eliminated mix-ups. If low on cartridges, you could load either gun.

The .44-40 is said to have killed more people, good and bad, than any other commercial cartridge. Given its long service in lawless places, that’s a credible claim. It might have killed more had the plains tribes adopted it sooner. Oddly enough, even Colt revolvers languished in the dust of Indian ponies. Many warriors preferred arrows.

Archers

For centuries after gunpowder was invented, archers directed the course of history. At the Battle of Hastings in 1066, Normans tempted their English foes with a false retreat, then sent a hail of arrows toward oncoming troops, inflicting heavy casualties to win the day. England’s longbow was not so called for its tip-to-tip measure, but for the manner of the archer’s draw, with an anchor point at ear or cheek. Short bows of the day were commonly drawn to the chest.

The English adopted the Viking and Norman tactic of raining arrows into distant ranks. Advancing quickly in armor was no solution, as plate and mail wearied the men. English archers aimed for joints in the armor and for the exposed head of any soldier shedding his helmet on a hot day. They shot horses during a cavalry assault, not only to cripple and kill but also to make the steeds unmanageable and spill their riders.

In those days, English conscripts were required to practice with bows. Poachers were pardoned if they agreed to serve the king as archers — a big concession, given the standard penalty for poaching was a hanging by one’s own bowstring! In 1542, an Act established no man of 24 years age or more might shoot any mark at “less than 11-score distance.” That’s 220 yards!

Yew was the preferred wood for English bow staves, but England’s yew didn’t match that of the Mediterranean for purity and straightness. Spain forbade the growing of yew on the premise it might find its way to England and thence to battlefields where Spain might feel their sting. Desperate for staves, the English countered by requiring that yew staves be included with every shipment of Mediterranean wine!

Indian Bows

In North America, bows with wide, flat limbs were shaped from soft woods like the yew favored in the Pacific Northwest. Indians used ash, hickory and other hardwoods in the East, Osage orange in the Midwest.

Some tribes applied sinew to add cast and protect a bow’s back at full arch. Horn on the bow’s belly gave resilience under compression.

Bows fashioned by Eastern Indians were long and beautifully made. Accuracy mattered because one shot was all that could be expected. On the plains, shorter bows evolved as horses became available. Where hunters rode alongside bison and shot repeatedly up close, precision counted for less, and arrows seldom survived. Fletching was long because the crude shafts needed strong steering and feathers spent little time against the bow handle before the shot. Raised nocks aided the “pinch” grip.

Albeit generalizations are perilous, it’s no stretch of logic to say the Plains Indian pushed his bow as much as he pulled the string. This technique enabled him to shoot quickly and get lots of thrust from a short bow. Due to limitations imposed by bow material and his horseback perch, he drew well shy of the arrowhead. But even a 20″ draw stacked enough thrust to drive arrows through big animals.

“Bigfoot” Walker, the Texas Ranger who helped Colt develop its huge Walker revolver, remarked, “I have seen a great many men in my time spitted with ‘dogwood switches’… [Indians] can shoot their arrows faster than you can fire a revolver, and almost with the accuracy of a rifle at the distance of 50 or 60 yards.”

Pistoleers unfamiliar with bows might think this a hyperbole. Not so. The French learned at great cost that archers in England’s army could launch 10 shafts a minute, 240 yards with good accuracy. Near the village of Crecy-en-Ponthieu, 26 August 1346, the English rained arrows on charging French cavalry. If heavy horses in battle trappings took 90 seconds to cover the 300 yards to the English front, they and their riders would have endured a hail of 7,500 arrows from a wedge of 500 archers.

The 5,000 bowmen in this epic brawl each probably had 100 shafts on-hand. Struggling up a slope bloodied with dead and writhing foot soldiers, the French knights met a fearsome storm of steel. By one estimate, English archers loosed half a million shafts that day, leaving “the flower of the chivalry of France” dead upon the field.

Dr. Saxton Pope, credited with bringing the bow into the 20th century after learning about it from a lost Indian he tended in California, tested arrow penetration on early armor. An attendant offered to don the 25 pounds of steel and stand for a shot. The doctor demurred, putting the armor on a burlap-padded wooden box. From seven yards, his bodkin-tipped shaft punched through the thickest part of the back armor, penetrated an inch of wood and bulged the chain on the breast side. The attendant paled.

Experience Matters

After that preamble, you’re licking your chops, expecting a toe-to-toe speed and accuracy contest. Alas, a few shots with my bow and a Single Action Army revolver confirmed I’m not skilled enough with either for such trials. Competence with bow or pistol comes hard. A handgunner might shoot a bow well, but not at the level of a practiced archer. And vice versa. An Indian teethed shooting arrow would hardly have the chance to become skilled with a Colt if he came by it, and a half-empty cartridge belt, in battle.

Long experience matters in any sport; muscles developed from youth for specific actions can’t be trumped by those trained in adulthood. In 1545 the French fleet sunk an English ship, the Mary Rose. A 1979 salvage operation brought up a thick, “knobbly” stick — a bow stave. Inspection, however, showed horn nocks and tillering (trimming limbs to match and speed them). A finished bow! Logic supported the finding — England wouldn’t have filled a warship with staves. But how could 16th-century archers, smaller than people now, have drawn such a massive bow, duplicates of which pull to 160 pounds?

Answer: Boys of that time shot often and with bows of increasing strength, from very young age into adulthood. In the early 20th century, Howard Hill did too, loosing his first shafts at age four. Not a big man, Hill came to favor very heavy bows, including a 172-pound longbow he used to kill an elephant. He wrote of hitting a pronghorn on the run at 70 steps, of skewering an elk at 185. He shot for Errol Flynn in the 1938 film, The Adventures of Robin Hood, and produced 23 reels on archery for Warner Brothers.

A Test Anyway

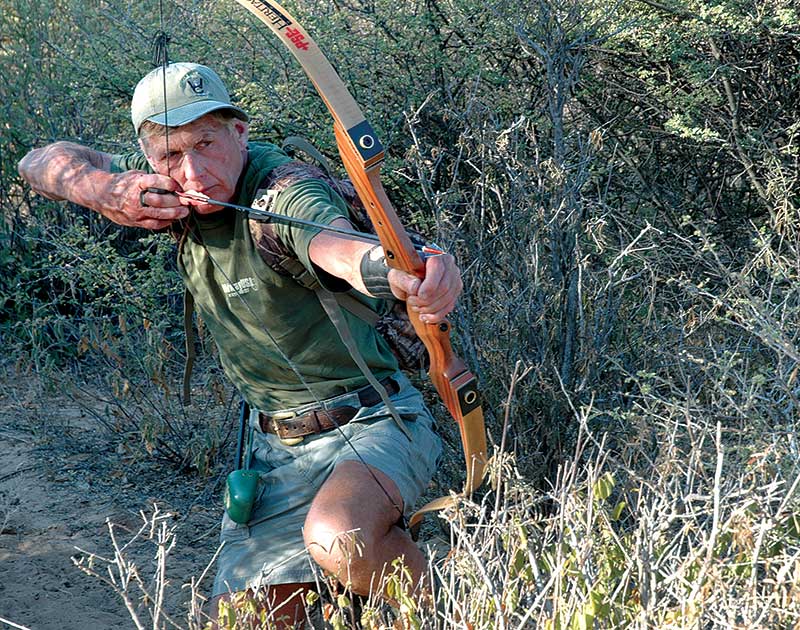

Okay, I had to do it. Equal incompetence with bow and revolver, I surmised, qualified me for those time and accuracy comparisons. I chose 15 yards as the distance — double hip-shooting range for old-school combat training, but closer than I’d get to a hostile Indian with a bow, or a gunslinger brandishing a Peacemaker. I scrounged a Colt SAA in .38 Special and Speer ammo with 140-gr. JHP bullets. My PSE recurve bow has no sights; it pulls 55 pounds at my draw length of 3″. The 51/2″ “black” of a 25-yard pistol target would be the mark. I’d try to hit with six shots quickly, emptying and recharging the Colt to ready it for a seventh. Same for the bow. Of course, the SAA could be fired faster, but the bow would be empty for a fraction of the time I needed to clear and reload a cylinder from my cartridge belt.

I’ll spare you the embarrassments and triumphs of practice sessions and report here the last result as typical.

Firing at a rate of a shot every 21/2 seconds, I kept five of my six revolver bullets in the black, in a 41/2″ group. Predictably, one of my arrows flew wild too, five shafts tearing a 4″ crater. Handgun time, including reload: 62 seconds. All my arrows were gone, with another on the string, in 56.

These trials suggest the bow trumps the pistol for more than six shots. You’re no doubt itching to point out a bow requires more space to operate, and, unless you can clasp a bareback pony with one knee at full gallop while muscling a 55-pound bow to full draw under its neck, a lot more exposure. Given a dead horse or a rock for cover, a man with a bow is more vulnerable than one with a Colt — which can also be fired easily with one hand.

In the 1870’s West, I’d have missed ridiculously close shots trying to save my scalp with a sixgun. Even modest competence is easily erased by panic. But had I, as an Indian, survived the hail of pale-face lead sent my way in a dust-up, I’d certainly have swept up any Colt I found in the dust. You see … my one effort at knapping an arrowhead failed miserably.