Military Use

Following the Colt/Walker there were three redesigns of the basic Dragoon .44, but they all had 71/2" barrels and weighed slightly in excess of four pounds. Their cylinders were likewise reduced from 19/16" to 17/16" in length, which made powder capacity about 50 grains. In 1860 the last Colt .44 cap and ball sixgun appeared and was a completely new design. All its contours were rounded and for some reason barrel length grew a half-inch. It “only” weighed about 42 ounces. Chamber capacity was 35 to 40 grains of black powder.

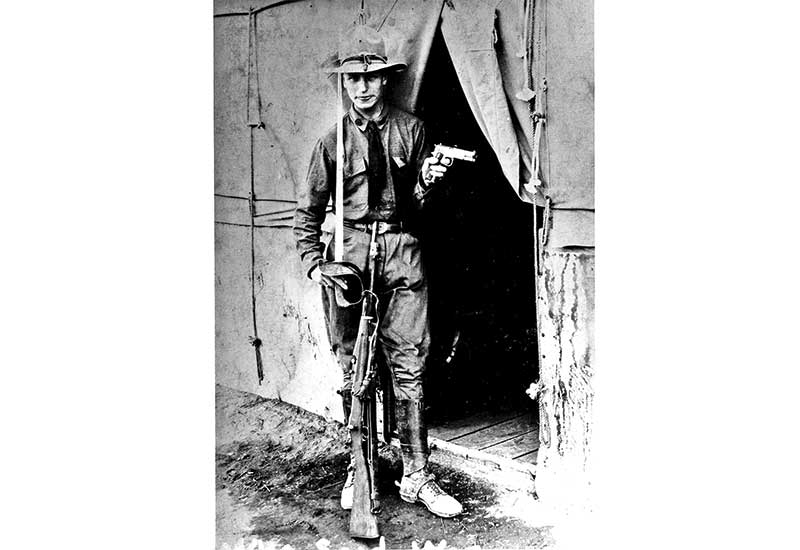

There was one thing all Colt .44 cap and ball sixguns had in common. They were developed expressly for military use. Most certainly some Walkers and Dragoons were sold on the civilian market but they were too heavy for practical belt carry. In fact the military issued saddle holsters for them. Only with the 1860 did a .44 Colt become feasible for everyday wear on the person for both civilians and troopers. Of course, the smaller, lighter .36 Navy Colts were extremely popular on the commercial market. Much like today’s civilian market tending toward easier-to-carry handguns like “medium”-sized revolvers or autos.

Collectively all three Colt .44 Dragoons were made to the tune of a few hundred over 20,000. Ten times as many Colt Model 1860’s were made. These figures count those sent to the US Government and those sold commercially. Possible velocity figures for these .44 cap and balls with 148-grain round balls are, for the Walker, 1,200 fps; Dragoons, 1,050 fps and Model 1860, 850 fps. I got these figures from actually shooting my own 2nd Generation versions.