They Were Great Handguns...

But They Weren't That Great

Some handguns were just downright wonderful. They were put together better, finished prettier and shot more accurately than most of their contemporaries — or anything made today. These fine old handguns were made in the era when American production quality surpassed Swiss watches. Handguns like the Colt Peacemaker, S&W Triplelock, Colt New Service, Ruger’s Blackhawk .44 Magnum and Colt 1911 have all achieved legendary status. At least that’s what you’ll have read if you follow the writings in gun magazines for over 40 years like I have. Heck, I’ve even written such stuff myself.

To be honest those handguns weren’t all that great. I know, because I have several samples of each. The greatest thing most have going for them is they are no longer made, which in turns makes them desirable. Tell someone they can’t have an item and watch it turn into a collector’s piece overnight.

Now, I’m not saying the above handguns were bad. They all have their good points. But they all, indeed, had their bad points. That they were “wonderful” shouldn’t be considered a legend — it should be considered a myth.

Duke test fired these five S&W .44 Specials with the same handloads on the same day.

Guess which one was most accurate? Top to bottom: Hand Ejector, 1st Model “Triplelock”

4", Hand Ejector, 2nd Model 61⁄2", Hand Ejector, 3rd Model“ Model 1926 5", Hand Ejector, 4th

Model “Model 1950 Target” 61⁄2 " and Model 21-4, 4".

Huh?

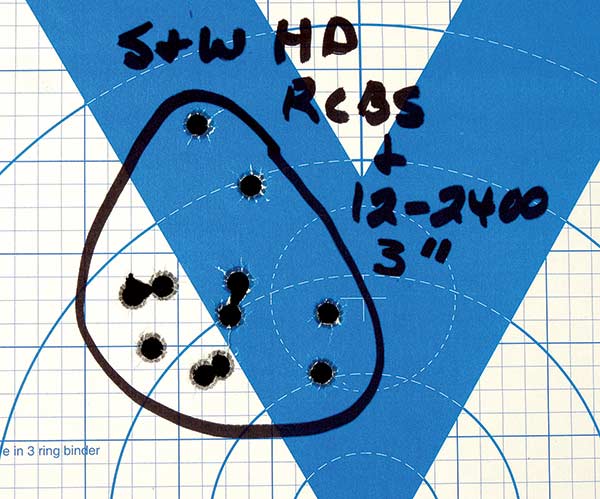

Here’s a good example. Pre-World War II S&W N-frame revolvers are considered the “best of the best.” For several years I owned one of the Heavy Duty .38-44s, which meant it was chambered for .38 Special, but intended for those odd .38-44 high pressure loads that came out in 1930. Such loads were actually the precursor of the .357 Magnum. The dual digits meant the caliber was .38 but they were only intended to be fired in .44 frame-sized handguns.

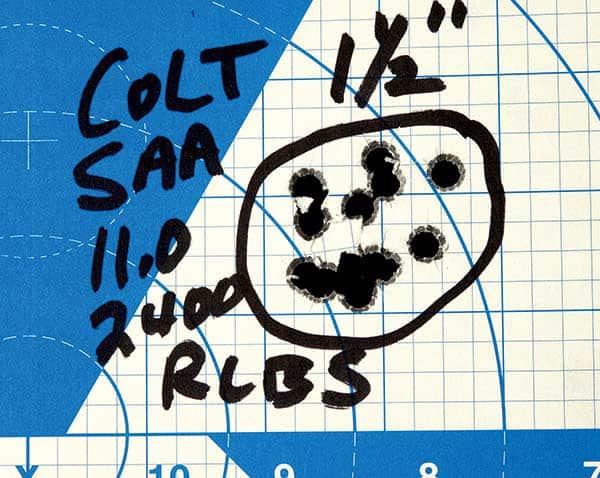

My particular Heavy Duty was shipped from the factory in 1931 and was in beautiful condition, with 90-percent or more of its bright blue finish remaining, with perfect lock-up and timing, and with nary a bit of pitting in its 5″ barrel or chambers. So last summer I determined to do a reloading project using it and a Colt SAA .38 Special of about 1960 vintage since it was also rated safe for those high pressure .38 Special/.38-44 type loads.

That Heavy Duty would not group any load under 3″ for 10 shots at 25 yards. The Colt SAA put some of the exact same loads into 11⁄2″ groups. Furthermore, I also have a 1950s vintage S&W Outdoorsman .38-44, which is the same basic handgun as the Heavy Duty except it carries adjustable sights instead of fixed ones. That post-War World II Outdoorsman shot rings around the pre-World War II Heavy Duty, with most of its groups being less than 1 1⁄2″.

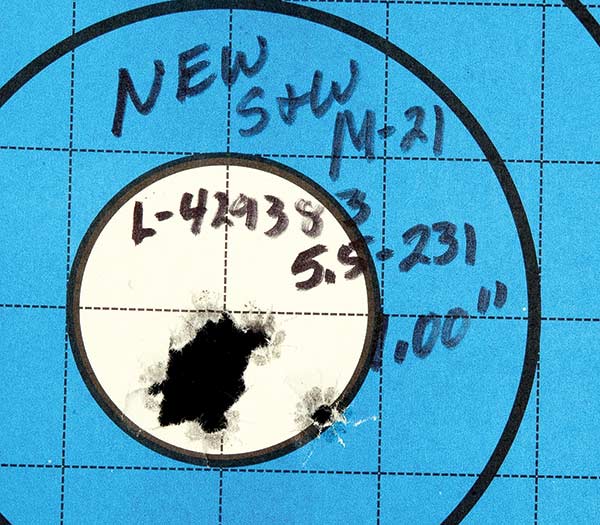

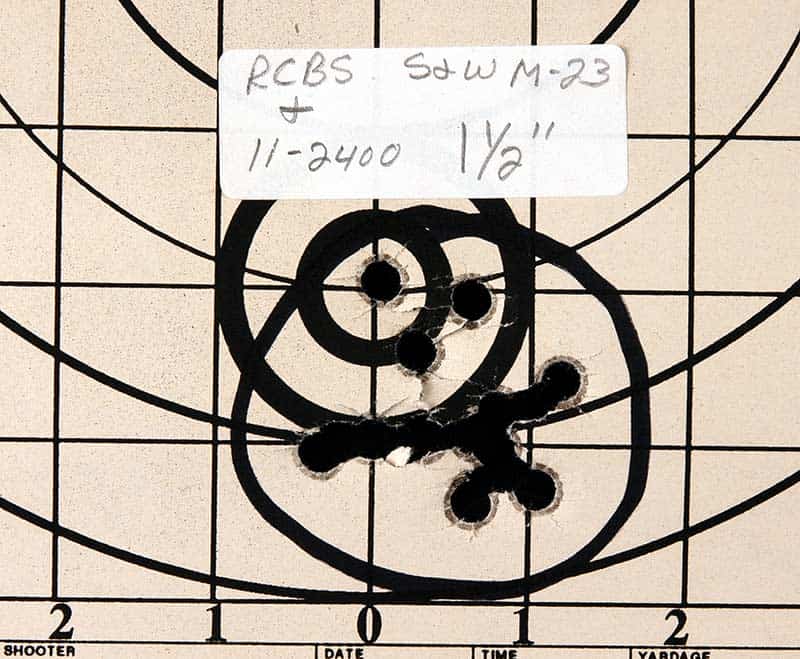

OK, let’s carry this matter a step further — in each direction. I mean let’s compare pre-World War I Smith & Wesson N-frames to brand new Smith & Wesson N-frames. No American revolver has the mythical aura of the Smith & Wesson Hand Ejector 1st Model, commonly known as “triplelock.” That’s because Smith & Wesson fitted it with a third lock, which secures its crane to frame when the cylinder is closed. It was introduced in 1908 and dropped in 1915. Some consider it the finest revolver ever made, and indeed its fit and finish is unsurpassed. I have two; one a target sighted version with 61⁄2 barrel and the other a fixed sighted one with the very rare 4″ barrel. Neither one is especially accurate. In fact my 2004 vintage S&W Model 21-4 “Thunder Ranch Revolver” shoots better than both. It’s true you can actually see yourself in the fine finish of good condition Triplelocks, but I’ve never needed to use my revolvers as shaving mirrors. I shoot them, and not being a world class handgun shot I need them to be accurate to compensate for my lack of skill.

Colts Too?

Now unless you think I’m picking on S&W revolvers let’s hammer Colts for a while. Probably no current gun’riter is as identified with the Colt SAA or Peacemaker as I am. That doesn’t mean I think they are beyond reproach. Anyone who has measured a passel of Peacemaker barrels and cylinders realizes some of Colt’s engineers from the bygone era were asleep at the wheel or at the reins, depending on the era.

For instance, it’s well known pre-World War II Colt SAAs in .45 Colt were given barrel groove diameters of .454″. Then when Colt resurrected the Peacemaker in 1956, they reduced that measurement down to .451″. Everybody with me to this point?

Well, what’s not so well known is Colt seldom worried about matching the Peacemaker’s cylinder chamber mouth measurements to their barrel diameters. I’ve encountered pre-1900 SAA .45 Colt cylinder chamber mouths as small as .448″. Picture that — a bullet starting at .454″ is squeezed down .006″ as it leaves the cylinder, then it enters a barrel way too small. What allows this system to work at all is the “bumping” properties of black powder, coupled with dead-soft lead bullets. They sort of mush about; swelling or squeezing as needed.

The problem wasn’t restricted to only pre-1900 SAAs or to the .45 Colt. I once owned a Peacemaker .32-20 having a barrel groove diameter of .314″ but chamber mouths of .310″. You couldn’t hit a John Taffin hat with the thing. And .38-40s were a hoot. Every .38-40 Colt SAA I have ever seen made prior to 1941 has had a tiny .41 stamped beneath the barrel. In fact Colt used the same barrels for .41 Colt and .38-40 sixguns. They were supposed to be .400″ in the grooves. I’ve slugged many and found them to measure from that to .408″.

Likewise I’ve seen 1st Generation .38-40 cylinders with chamber mouths as tight as .398″ and as big as .404″. Conversely, I’ve owned at least a half dozen 3rd Generation Colt SAA .38-40s made in the 1990s. One and all, their barrels measure .400″ and their chamber mouths measure .401″. They will shoot rings around the 1st Generation .38-40s.

When Colt resurrected the Peacemaker for its 2nd Generation in the 1950s they reduced barrel groove diameter to .451″. Some I have slugged are closer to .450″. No problem there, except Colt made the chamber mouths huge. I’ve never encountered a 2nd Generation .45 Colt SAA with chamber mouths smaller than .455″ and some have been a whopping .458″. The reason the .45 Colt cartridge doesn’t have a sterling accuracy reputation isn’t inherent to the cartridge itself — it’s a problem of mismatched dimensions in the handguns.

In gatherings of big bore revolver shooters many will genuflect when someone uncases

one of these vintage handguns. At left are a Colt New Service .38-40 and a Colt U.S. Mdl.

1911A1 .45 ACP. At right are a Ruger Blackhawk .44 Magnum and a Colt SAA “Peacemaker”

.45. In middle is a S&W Hand Ejector, 1st Mdl. Target (Triplelock) .44 Special.

That’s Not All

Now let’s pick on the Colt New Service for a bit. I’ve only owned a few of these behemoths so I certainly don’t consider myself an expert on them. Right now there are two in my collection; a .38-40 and a .45 ACP Model 1917 version the U.S. Army bought during World War I. Both shoot adequately; in fact my 1917 can be downright impressive with some handloads. My complaint about them is someone needs gorilla-sized fingers to reach the trigger for DA shooting. The distance from the grip to the trigger is so long, I can barely get a finger around to it. In fact I asked my wife, Yvonne, and found she can’t reach a New Service trigger with her index finger at all! I asked her to shoot the .38-40 double action one time and she couldn’t manage it.

Now I’m going to be really brave and take a shot at the 1911 in these hallowed pages. Almost every reader here worships 1911s, but I’ll bet not many of you love it so much in its original configuration. The 1911s we all laud are the tricked-out ones with extended grip safeties, decent sights, accurizing, etc. I don’t know anyone who can shoot an as-issued 1911 and not get the web of their hand bloodied. Granted my hands are as fleshy as the rest of me, but still, why did John Browning design a pistol that would bite the shooter’s hand unless he was concentration- camp skinny? Getting smarter as I get older, when I shoot my World War II type 1911A1s, I put a band-aid on the web of my hand so I don’t bleed.

Another fault of the 1911 as designed is its sights are practically useless. As designed and adopted by the U.S. Army, either as the Model 1911 or the Model 1911A1 it was such a difficult handgun to shoot by the beginning of World War II, American military higher-ups were considering doing away with handguns altogether. The whole rationale behind the development of the M1 Carbine was to replace the 1911s in troops’ hands because they couldn’t hit anything with them anyway. The idea was a hit with a puny caliber from a carbine was better than a complete miss with a big honker from a pistol. That pistols were never entirely replaced by carbines is a testament to how comforting one is to a soldier, and not how well he could shoot a 1911.

Hand Destroyer

Let’s not close without trashing Ruger a little bit too. In any gathering of big bore revolver shooters some automatically genuflect at the sight of one of those 1950s vintage Ruger Blackhawk .44 Magnums. They were only made for a few years, and rightly so. Being fitted with an aluminum alloy grip frame they are light. With full power .44 Magnum ammunition they will just plain brutalize you with every pull of the trigger. The trigger guard whacks the middle finger of the shooting hand, and I’ve actually known of people who fired their first shot with

one held rather loosely and have had the revolver bounce off their skull during recoil. They are not fun shooters. There was a reason they were only on the market a few years.

Just because a handgun model has ceased being made doesn’t make it legendary. It just makes it discontinued. There may be a reason why it didn’t sell so great in the first place.

Subscribe To American Handgunner

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: