The First Big-Bore Sixguns Part 3

The .44 Army Models

The Paterson, the Walker and the various Dragoons were all great improvements over the single-shot pistols in use before Sam Colt arrived on the scene, however life is full of trade-offs. The Paterson was light and easy to pack but lacking in power and quite fragile. The Walker and Dragoons had plenty of power, their four-pound plus weight made most shooters hesitate to carry one, much less a pair, and they were more than a little heavy for fast work from a holster. The advent of the 1851 Navy .36 introduced a truly packable, 21/2-pound sixgun, which could be carried securely high on the belt in a Slim Jim holster and be nearly instantly accessible. With the entrance of this scaled-down Dragoon, a man was as dangerous with his sixgun in a properly designed holster, as he was with the sixgun in his hand. Perhaps even more so as any practiced sixgunner can draw and fire a single-action sixgun faster than the average person can react.

For the first time real speed from leather was possible. The age of the gunfighter had arrived. However, it should be noted most gunfights began with guns in hand. Not just a few were settled with shotguns to the back. That most notorious pistolero, Wild Bill Hickok, carried a pair of ivory-stocked 1851 Navies, though not in holsters — but rather butts to the front in a sash about his waist. Bill did not operate these Colts crossdraw style but rather by using a strong side twist draw. His style was carried out in the movies and TV by Wild Bill Elliott and Guy Madison, although both used holsters instead of a sash.

Hickok was still carrying this pair of cap-n-ball .36 sixguns when he drew the poker hand now known as the Dead Man’s Hand just before being shot from behind in 1876. Bill apparently did not believe in progress nor fixing what ain’t broke. He certainly could have laid his hands upon the Colt Single-Action Army .45 or a Smith & Wesson .44, however he still preferred a pair of Colt 1851 Navies. As beautifully proportioned as the 1851 Navy was it was still a rather small-bore pistol. But Hickok was a deadly marksman with virtually no fear so the .36 was all he needed. However, there was a real need for the same type of design — shooting a .44 ball.

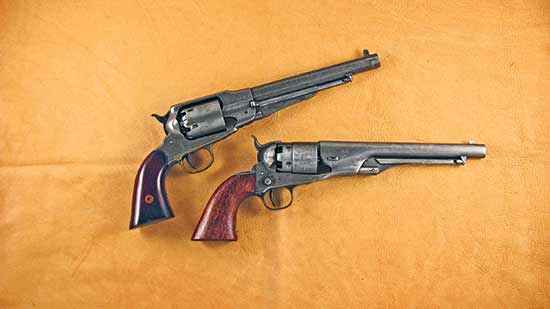

The Colt 1860 Army

It was time for a new big bore sixgun and Sam Colt and Elisha Root worked together. The result in 1860, on the eve of the War Between the States, is what I consider the apex of Colt’s cap-n-ball sixguns. The 1851 Navy was perfect for holster use but carried a small payload. Now metallurgy had improved to the point Colt could use the same basic frame size as the 1851 Navy to make a .44 sixgun.

This was accomplished by using a two-step cylinder, smaller at the back than at the front, with a cutout at the front of the frame to accept the larger cylinder and by doing so it was possible to come up with a .44 caliber revolver which was almost as trim as the 1851 Navy. Basically, the Colt 1860 Army .44 carries a Dragoon size grip frame on a Navy main frame. With the rebated cylinder larger at the front, it’s able to hold a full 40 grains of black powder under a .44 caliber ball.

The barrel length was 8″, and the loading lever was streamlined to flow naturally into the frame rather than having the blocky appearance of the 1851 Navy. The grip frame was made slightly longer to handle recoil. Many sixgunners consider the streamlined 1860 to be the most beautiful of all Colt’s percussion revolvers. As a kid I found a picture of an ivory-gripped 1860 with a tooled holster and I dreamed over it for years.

Curiously enough, in 1873 when Colt went to the Peacemaker chambered in .45 Colt, instead of using the more recoil comfortable 1860 Army grip frame they reverted back to the grip frame of the 1851 Navy. My favorite shooting 1860 replica is one with the antiqued finish, and I have fitted it with a Colt SAA grip. Actually I swapped grips with a like-finished .45 Colt. The longer grip frame is sometimes necessary with the heavier .45 Colt loads, however it’s not needed, subjectively speaking of course, for loads in the 1860 Army. The New Model Army Pistol, known to collectors and shooters as the 1860 Army, weighed 43 ounces, or just three ounces over 21/2 pounds. This was quite a savings in weight compared to the 4 to 41/2 pounds of the Walker and Dragoons.

Army Adopts

The 1860 Army was tested by a board of Army officers and in May of 1860 they announced, “The superiority of the Colt revolver, as an arm for cavalry service, which has been so well-established, is now finally confirmed by the production of the New Model with the 8″ barrel. There are a few minor points requiring modification, to which the manufacturer’s notice has been called, and to which he should be required to attend in any arms of the kind he may furnish for government use.

“The Board is satisfied that the New Model Revolver with the 8″ barrel will make the most superior cavalry arm we have ever had and they recommend the adoption of this New Model and its issue to all mounted troops.”

From 1861 to 1866 the Ordnance Department would purchase nearly 130,000 New Model Revolvers, and the civilian population also enthusiastically bought the new .44, all of which combined to place the Colt factory on very solid footing and make Sam Colt a rich man. Unfortunately, Sam Colt did not live to see all of this as he died in 1862. In one of life’s strange twists and turns, the head of the Army Board which approved the adoption of the 1860 Army for mounted troops would very shortly find himself on the side of the Confederacy that now faced the new revolvers in the hands of the Northern troops. The only way the South could acquire 1860’s was by taking them off Northern soldiers. The 1860 would live on after the Civil War, finding much use on the frontier. Even after fixed ammunition revolvers were adopted, the famed Buffalo Soldiers were armed with 1860 Army Colts.

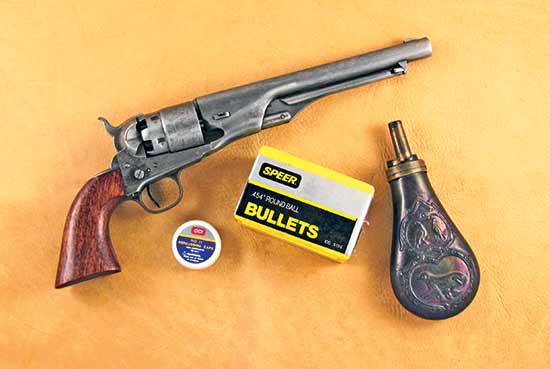

I have several 1860 Army Colts at my disposal, however my favorite is the antique finish model. With 0.454″ Speer round balls, CCI #10 percussion caps and 30 grains of Pyrodex P black powder substitute — with a Wonder Wad in between powder and ball — it results in a very pleasant shooting 700 fps and 5-shot groups at 20 yards of 15/8″. Upping the charge to 40 grains with a .451″ round ball gives more than 1,000 fps and five shots into 11/8″. With the right combination these replica Colts will shoot right alongside, sometimes even better than modern handguns.

The 1858 Remington

“It never failed me,” so said William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody of his Remington New Model Army .44. Cody’s experience with his .44 Remington began in 1863 when he joined the Union Army and lasted until 1906 when he wrote a note on the back of his business card and gave it and the Remington to his ranch foreman and his wife. Cody testified he had used it for many years both while fighting Indians and killing buffalo and it had never let him down. Cody’s Remington was a standard New Model Army serial number 73293, blued finish and fitted with ivory grips. At a time when almost every other famous or infamous frontier character was using a Colt, Cody stands out as one of the few who is reported as carrying a Remington.

If I had lived at that time I wonder if I would have chosen the Remington Army .44 or the Colt Army .44? Looking back from my vantage point I see the Remington is definitely superior in design. Colt’s 1860 Army consisted of a mainframe with a removable barrel assembly, trigger guard and backstrap. Add in the cylinder and it’s made up of five main pieces. The Remington was a solid affair with only the cylinder easily removable, the barrel solidly screwed into the frame, and the entire grip frame simply an extension of the mainframe.

The sighting arrangement is quite different on the two sixguns. The Remington has the traditional trough across the top strap that would later be found on all Colt Single Actions as well as the Smith & Wesson Military & Police, while the rear sight of the 1860 Colt is a notch cut in the top of the hammer. However, at least in my hands, the 1860 Army has two major advantages. The grip frame is much more comfortable and the balance also seems to be much better. My fingers are pinched between the back of the trigger guard and the front strap on the Remington design and, again for me, the 1860 Army point shoots more easily than the Remington.

Two years after Sam Colt was born, Eli Remington made his first rifle barrel. The company he started became E. Remington & Son in 1839, and as another son joined the business, Remington became E. Remington & Sons in 1845. All of this makes Remington America’s oldest gunmaker. Not only does Remington pre-date Colt, Smith & Wesson and Winchester, they also produced a much larger assortment of both handguns and long guns.

The Colt 1860 Army is usually considered as the Union Army revolver during the Civil War. However, Colt accounted for 39 percent of the firearms purchased by the government from 1861-1866, while Remington was right behind them with 35 percent of the total. Remington supplied the Union forces with slightly over 125,000 .44 caliber revolvers. At a time the Colt was selling to the government for just under $18, Remingtons were $13. It would be interesting to know how much each revolver actually cost to produce to really be able to compare these two figures. My guess is Colt made a whole lot more profit off the war than did Remington.

The Remington design comes from a patent held by Fordyce Beals. The first Beals’ revolvers were pocket style with the Army .44 arriving in 1858. This was improved to the 1861 Army and then the New Model Army .44 arriving in 1863. With the Model of 1863 it was necessary to lower the loading lever to be able to draw the base forward and the base pin could only be drawn forward far enough to remove the cylinder.

A new feature was the addition of notches cut between the nipples at the back of the cylinder to provide a resting place for the hammer nose instead of on a loaded chamber. Allowing the hammer of any single action revolver to rest on a cap on a loaded cylinder percussion revolver, or on the primer of a loaded round in a revolver made for fixed ammunition, or using the so-called “safety” notch on the hammer with all chambers loaded — are all invitations to disaster. Never, never, ever trust the so-called safety notch or allow the hammer to rest on a loaded chamber.

Replicas of Remingtons available today are designated as the Model of 1858 but they are actually closer to the Model of 1863. However one chooses to designate them they’re well-made, accurate sixguns, and like so many other replicas available today provide us with a great link to the past. The Navy Arms Deluxe 1858 Remington has proven to be an exceptionally accurate revolver, often outshooting currently produced “modern” revolvers.

Shooting

For this particular percussion sixgun I use .454″ Speer round balls and Remington #10 percussion caps. With 30 grains of Goex FFFg over a Thompson Wad, muzzle velocity is 750 fps with a 5-shot group at 20 yards of 11/4″. Stepping up to 40 grains of the same powder with Crisco as a lube results in 1,055 fps and a slightly tighter group of 11/8″. Pyrodex P also performs exceptionally well, with 30 grains and a Thompson Wad resulting in 650 fps and a 1″ group. Interestingly, 35 grains with Crisco as a lube increases the muzzle velocity to 820 fps and tightens the group to 3/4″. All charges are by volume not by weight, don’t forget!

I also have an 1858 Remington with the same antique finish as found on the above-mentioned Colt 1860 Army. Using .454″ round balls and Wonder Wads over 30 grains of Pyrodex P and ignited by a #10 percussion cap gives 750 fps and a 5-shot, 20-yard group of 11/8″. Upping the charge to 40 grains of Pyrodex P and using a .451″ ball increases the muzzle velocity by 300 fps, with a group of 11/4″ for five shots at 20 yards. Just as with the Colt 1860 Army the Replica Remington will also outshoot many modern handguns.

Conversions

With the coming of the first cartridge-firing big-bore sixgun in late 1869, the Smith & Wesson .44 American, many Remington and Colt cap-n-ball sixguns were converted to cartridge-firing, sometimes by the factory, sometimes by local blacksmith/gunsmiths. Colt offered the Richards and Richard/Mason cartridge conversions around 1870, both of which were built on Colt 1860 Army revolvers fitted with a cartridge cylinder, loading gate and ejector rod.

These were followed by the 1871-72 Open-Top Colts which, although they looked like the Cartridge Conversions, were built from the beginning for cartridges, namely the .44 Colt. In 1873 the Open-Top evolved into the Colt Single-Action Army. Remington, with a special contract with Smith & Wesson, began offering cartridge-firing sixguns, even before Colt. Of course, the Remington Cartridge Conversions evolved into the 1875 Remington Single Action. Today cartridge conversion cylinders in .45 Colt and .45 ACP are offered for use in replica percussion revolvers.