You Don't Need That — On Simplicity

A defensive gun has to work, all the time, and you have to be able to hit with it. This simply means the pistol must be capable of reasonable accuracy, and you must be able to deliver this accuracy through your interaction with the gun’s sights and trigger. Sights, trigger and reliability — these come first. Then we can move on to the finer intricacies of the pistol’s interaction with your hand. We’re looking for the best accuracy, the surest, safest handling and the highest speed — eventually. The human factors we call ergonomics, usually distill down to controls, contours and texture.

There’s a certain knee-jerk reaction to controls, saying bigger is always better. Much of this comes from IPSC and other forms of competition. Extended, ambidextrous mag-catches and slide-stops, thumb safeties with huge levers and more are said to be “needed.” But you don’t need them, and some of it is a liability.

In its more extreme forms however, competition is very different from defensive shooting. And in all forms, the consequences of equipment failure or mis-manipulation are far different. We’re talking about surviving a fight for your life you didn’t start and can’t opt out of. Failure doesn’t mean trying to shoot better next week. If a modification gives you a marginal edge but causes stoppages or problems — it has to go.

Faster Or Fumbly?

I’m not a fan of extended mag releases or slide-stops since both make it more likely you’ll activate them accidentally. Controls that can shut the gun down, with the sole exception of the safety, should be standard size. Controls you use intermittently shouldn’t be positioned (too big) where they hamper ordinary function.

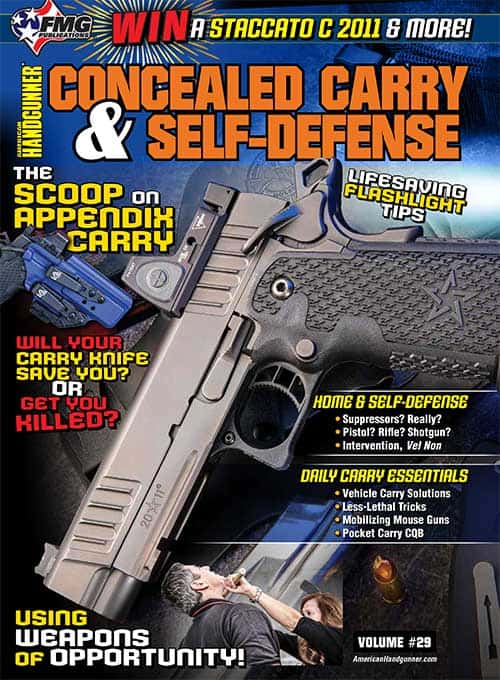

Larger thumb safeties, especially on 1911-pattern pistols — which used to come equipped with safeties the size of a zipper tab — increase your ability to hit them in a hurry. This theoretically makes the pistol’s operation more certain. The tradeoff is the larger the thumb safety, the greater the chance your hand, inertia, or some combination of the two will knock it back into the “on” position, shutting down the gun.

This problem is why many schools train you to shoot “high thumb” with your thumb riding the safety. It keeps your hand from knocking the safety up during recoil. It helps, but on a 1911 it creates a problem when paired with a beavertail grip safety. Beavertails keep the hammer from biting you, spread recoil across a larger part of the hand and allow the pistol to ride lower, reducing felt recoil. The high-thumb grip also changes the part of your hand contacting the grip safety. The top of the hand pushes against the curved underside of the safety, effectively trying to put it on. This interaction of thumb and grip safeties explains the design of many beavertail safeties, including “speed bumps,” high undercuts and the existence of the Wayne Novak-designed “Answer” — a one-piece backstrap eliminating the grip safety entirely.

If you can’t train your hand to work both reliably, options include a smaller thumb safety tab you won’t knock on, or modifying the engagement of the grip safety.

Grip Changes

The contours of the frame affect how the gun functions in the rest of the hand. The lower a gun sits, the less felt recoil it has. Look for a pistol to sit as low as possible in the hand without interfering with slide movement. With many pistols, the shape of the frame is a function of design and can be smoothed but not much else.

On the easily modified 1911, many beavertails sweep high enough to let the rear of the gun sit substantially lower in the hand. The base of the trigger guard should be modified too, extending the front strap upward so the front of the gun rides lower as well.

What about texture? Ideally, you want the gun to slip quickly into your hand when you grasp it, but lock in-place when you squeeze it. It should also stay in place if your hand is sweaty, bloody or whatever.

I don’t usually like rubber-like grip panels since their stickiness can drag on clothing and make it harder to reposition your grip. Finger-grooves similarly usually require your grip to be perfect when you grab the gun; hard to do under stress. On working guns, I prefer grips made of wood or a machined composite such as G10, which takes quite a beating.

While checkering on pistol frames is a perennial favorite, some of the alternative treatments, such as the matting found on Novak Hi-Powers, are more comfortable. The chain link type machined texturing on the Nighthawk’s Heinie pistols is snag-free, but offers purchase on demand. The harder you grab, the harder it grabs you back. While 25 LPI checkering has served me well as a compromise between the aggressive 20 and the finer 30, by the third morning of the week-long 250 pistol class at Gunsite, I dreaded closing my hand around the gun. Ouch.

Some things you’ll only find out through extensive use. Once your carry gun has the basics, evaluate the controls, the way the frame fits your hand and the contact surfaces of the gun. Modify them if necessary. People are all different, and there’s no perfect mix of features and dimensions for everyone to get the best out of a given pistol.

If it doesn’t work for you — it doesn’t work.

Get More Carry Options content!

Sign up for the newsletter here: