In Praise Of The Stock Trigger

Sometimes Bad Can Be Good

It’s fine to like nice things. No one should feel guilty for sleeping on sheets with a high thread count, driving a sports car, or wearing a watch eliciting compliments. Similarly, it is an absolute joy to own a well-made gun with a trigger breaking at exactly four-point-zero lbs. — the proverbial “glass rod.” I’d be lying if I didn’t admit to having several such gems in my collection.

In my younger days I’d have said the tools make the man. If you wanted to shoot at your best, you’d be doing yourself a disservice to not run the best equipment you could afford. Fast forward 10 years, and I’ve noticed my worst groups now are on par with my best groups then. I put on my big boy pants and gave this fact a real good think.

Today, I can state emphatically much of my growth as a shooter came from experience on platforms that, well — were not the best. To wit, handguns whose triggers were heavy and creepy, those with hitches and stacks, pre-travel and over-travel, and resets anything but crisp. So before you ship a new-to-you gun off to the gunsmith for what seems like an “essential” trigger job, see if something in these pages doesn’t ring true to you.

Devil’s Advocate

Let’s define a “bad” trigger. We’ll call it one with the worst qualities of a bad double-action and single-action trigger. Imagine you bring this imaginary gun up to eye-level and aim it at the target. You’d first need to pull through a long amount of pre-travel. Then you’d need to exert considerable effort to pull the trigger through its range of rearward motion, perhaps to the order of 14 lbs. or more, until the sear finally trips at some unknown point.

What would you need to do to shoot this gun well? First you’d need to bring the trigger through the pre-travel to the “wall” of the break, however long this may be. Then, you’d need build with increasing pressure, through heavy resistance, until the gun fires — since you won’t fully be aware of where that point actually is. To do so, you’d need to figure out some way of using gross motor skills to steady the gun in combination with the fine motor skills needed to manipulate the trigger finger. And, since the trigger itself is so unpredictable, you’d have no option but to rely on this technique every time, since it would be impossible to rely on a mash or a quick stab of the trigger to get a shot off with so much resistance.

Now let’s separate this nightmare of a trigger into two different components. Even with the best double-action triggers, DA shooting is hard for most because of the length of pull. Watch most novices shooting DA for the first time, and they’ll almost always mash the trigger straight through and flinch in the process. The instinct is to get the scary part over as fast as possible. Good DA shooting requires pulling straight through with an even and constant speed until — bang — the shot breaks. Even with heavy resistance, a smooth and deliberate pull is the way to go.

What makes a “bad” single-action trigger? The main complaint I hear is it isn’t crisp, but “mushy.” I offer this — consider it like a compressed double-action trigger. While it may not require nearly the amount of pressure to engage, the rules are the same. Pull straight through at a deliberate pace, regardless if the trigger creeps or if it stays put, and let the shot break where it will.

Don’t get me wrong, struggling with a gun whose trigger exhibits all of the negatives isn’t something necessarily fun or enjoyable. However, given these challenges, you can take to heart one incontrovertible fact — if you can shoot this gun well, you can shoot anything well.

Bugs Or features?

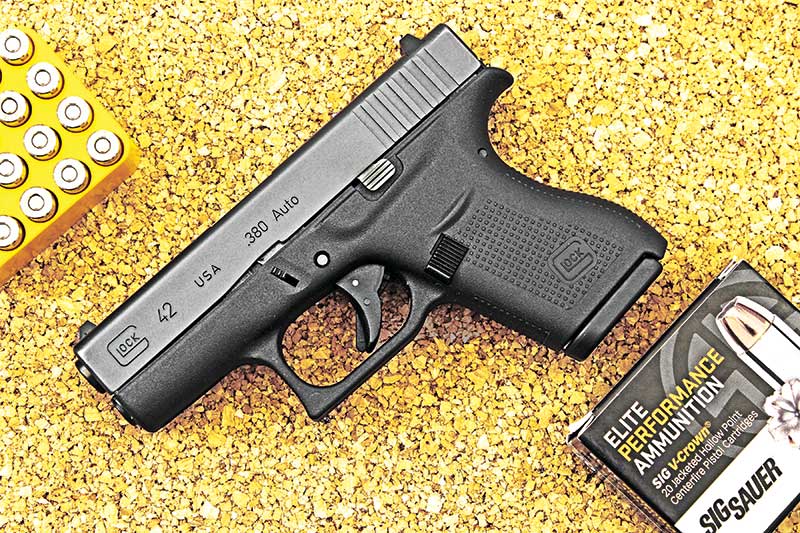

In certain cases, the tactile sensations of a “bad” trigger may have arisen because other design criteria were simply more important. I’ll be the first to mention most handguns are over-sprung. However, when a consumer says, “I want absolute reliability under any condition,” handgun engineers hear, “This gun should be able to detonate surplus, soviet-made primers in the dead of winter.” In revolvers especially, this means heavy springs and the inevitable heavy trigger pulls.

Can you reduce the spring weight? Definitely. But should you? Only if you understand the trade-offs you’re making. I used to swap out springs to get the lightest trigger pulls possible, even if it meant light primer strikes and sluggish trigger returns. Now, I’ve swapped heavier springs back into a lot of my guns, as the extra couple pounds of resistance bothers me less than hearing clicks without attendant bangs. If there’s even an off-chance I might rely on a gun for self-defense, I can guaran-damn-tee you I leave it stock.

Another sell on negotiating a stock trigger revolves around the dividends it will provide in building not only your technique, but your versatility. Hopping between various “okay” triggers builds awareness of how to negotiate guns on their own merits. A decade ago, I wouldn’t have given a second glance towards “Traditional Double Action” semi-autos, those whose first shot is fired DA, with the rest to be shot in single-action. Today, I can honestly say I would prefer to conscript a de-cocked Beretta 92 or HK USP to a self-defense role than a striker-fired design.

I like the notion of having the first trigger pull be long and deliberate like a DA revolver, requiring no futzing with safeties, and knowing follow-up shots can be pressed out in quick cadence if desired. Becoming familiar with two separate trigger pulls is not really a big deal once you’re familiar — nay, comfortable — with several suboptimal pulls.

Coming Full Circle

Broken and inconsistent triggers are terrible to deal with, and I’ve shot DA revolvers with such heavy pulls I thought I’d develop nerve damage if I kept up the effort. I wish these experiences on no one. However, go to a quality gun store and point your finger randomly at any new pistol or revolver, and the odds are very good you’ll pick a platform you can work with.

Additionally, new shooters don’t need any additional barriers to developing good marksmanship. Learning the fundamentals is easier when you don’t have to fight the gun in any way, shape, or form. So leave the Nagant revolver at home, okay? Also keep in mind laying the foundation for a great first range trip is often the best “activism” you can do to create a lifelong shooter and friend of the Second Amendment. Introducing too difficult a challenge to a novice — too soon — is always bad news.

For the rest of you, and barring the worst of the worst handguns, I maintain having experience with less than stellar triggers certainly will allow you to appreciate a good thing when it comes your way. After dealing with mushy 7-lb. single action triggers common to the military surplus world, a crisp, “glass rod” 4-lb. 1911 trigger becomes an utter delight. Even a regular old CZ-75 or Springfield XD becomes pretty damn great by comparison.

I’ve read more than a few times the real reason we take vacations is so we can come back home with a set of fresh eyes and realize how good we have things. Working with stock triggers is a great way to make you a well-traveled shooter, and likely able to take full advantage of whatever gun finds its way into your hands. As R. Lee Ermey said in Kubrik’s classic Full Metal Jacket, “Because I am hard, you will not like me! But the more you hate me, the more you will learn. I am hard — but I am fair.”