Once Upon A Time

In a Not-So-Distant- Future, Duke Explains Some Things

Dear younger readers, you may not be able to believe or even conceive of the following. It sounds like a fable, but I swear to you every word is true.

Once upon a time in America every handgun was made from steel. Oh sure some few had bits of brass here or there and of course all had stocks (today called grips) of some natural material. Usually that was wood, but sometimes ivory, horn, hardened rubber or even silver. And handguns all had a couple of factors men of the era also liked in females — curves and gracefulness. Nothing was square on handguns in the long-time gone past. There was symmetry and esthetics integral with most handgun design. Back then a handgun was not a mere tool — but a window into its owner’s true nature.

It is fact, handguns were completely made of steel. As far-fetched as it may sound every part of every handgun was cut from pieces of steel by machines that bored it, sliced it or threaded it. And every one of those machines had a man standing at it causing it to perform those intricate operations. That man didn’t just trip a lever or push a button. He had to know math and geometry and he had to be able to read blueprints. American handgun manufacturers employed these men by the thousands. They were called machinists and tool and die makers.

A Legion Of Talent

But the men cutting steel were not alone. Other men or women were necessary after the parts had been crafted. They actually fitted the parts together, in the process, smoothing them of burrs and culling out the rare piece on which the machinists might have made a mistake. These men were of another breed called “assemblers” and were so proud of their calling sometimes they were given a special mark to stamp on each handgun they put together so it could be traced back to them. When they got done with those steel pieces, a revolver’s cylinder would rotate the exact amount needed to align with the barrel or a semi-auto’s headspace would be perfect.

As strange as it may seem today a crew of handgun manufacturers was not complete without polishers and finishers. Being made of steel meant brand new unfinished handguns would start to rust immediately. And some steel usually needed hardening, but the process had to be specific to a part’s task and the steel’s composition. This required men who understood metallurgy. They performed magic on steel. Sometimes it changed color during the hardening process making it very pretty. That was called color case hardening. Other times, after a smooth hand polish, the metal was immersed in chemicals giving it a blue color. It may have looked black at a distance, but young people believe me — it was a deep blue.

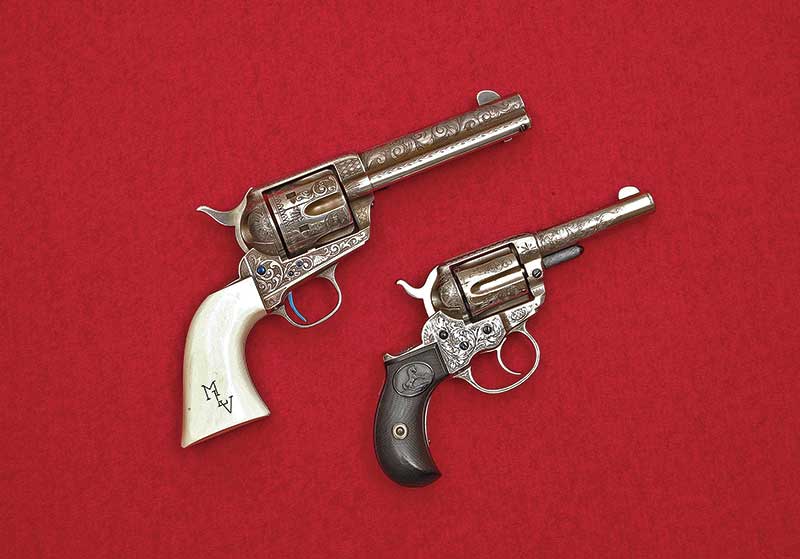

For a certain percentage of handguns made by most manufacturers, a blue finish was not applied. Some people had to be out in the elements day-in and day-out, or they lived near salt water or resided in hot areas and sweated on their handguns as they worked. Those folks preferred handguns with a coating of nickel applied. And because nickel-plating was also pretty it caught on with folks desiring a bit of fancy in their lives. You call that bling today.

Lastly, all the handgun factories had a now nearly extinct species of humans called quality inspectors. Their sole purpose was to check on the jobs done by all the above workers so no handgun left those factories with blemishes, or the slightest hitch in their function. Even though I was but a young whippersnapper back then, I remember knowing for certain when I took a newly purchased handgun from its cardboard (not plastic) box it would actually work to perfection. It needed no aftermarket slicking, easing, or parts replacement to work well.

Stocks

Let’s go back to that concept of stocks — or grips. There were actually people employed at large handgun manufacturers whose sole job was making those things. They had to be machine-savvy too, for some of those handgun stocks made by Colt Patent Firearms were cut from solid pieces of wood. Usually that was a type of wood called walnut, but sometimes more exotic woods came from places like South America. That wood was actually grooved all the way around so the two pieces of all Colt single action grip frames fit into it. Actual ivory from African elephants was treated in this manner too.

However, on other types of handguns by Colt and all other makers, most types of grips were wood and mostly they were two pieces fitted to the sides of a handgun’s grip frame, then held together with a screw. None were actually made as part of the handgun itself as is done today. Those stocks could be checkered or plain, fitted with medallions or not or made with just about any sort of embellishment the buyer wanted. Sometimes there were people so talented they could relief carve grips so one’s initials or special image stood “proud” or “above” the surface.

And speaking of talent, back in that era there were people at the larger gun manufacturers called engravers. They actually held little tools in their hands and cut the handgun metal with various designs. Even carved were little flowers or animals or insignias. And they made this art in steel by hand, not CNC or computer etching then, but with an artist’s eye and steady hand.

The Extras Too

In those days there existed a word nearly lost to handgun manufacturers today. It was the word “options.” You could buy your Smith & Wesson revolvers with such things as extra-wide hammers and triggers called “target type.” Then there were barrel length options. A long time gone there was a Smith & Wesson revolver called the “.357 Magnum” and later “Model 27.” Over a 60-year period it was offered with 31/2″, 4″, 5″, 6″, 61/2″, 83/8″ and 83/4″ inches as barrel length options. Finishes were also options.

As standard catalog items, Colt made their Single Action Army revolvers blued, with color case-hardened frame or full nickel-plated. And right off the shelf you could get them with 43/4″, 51/2″ and 71/2″ barrel lengths. If you have heard of cowboys, those were the types of guns they carried. Speaking of SAA’s and options, during a 75-year manufacturing period they could have been bought chambered for over 30 cartridges!

Once a guy or gal settled on his handgun preference in regards to options such as caliber, finish, barrel length and grip material, almost everyone then wanted a holster for it. Back in that era they were made of leather — the same type of stuff belts, shoes and boots were once made of. It was tough and durable and at this point I’m feeling a little maudlin — it actually smelled good. And there were also artists who could cut beautiful patterns and images into it.

And So?

I can hear you thinking, “What good was all that work and thought back in your day. Our handguns work fine today.” Well, the answer is, “Your handguns are often ugly. They are mostly black and square-shaped. They look all the same to me. Put 10 of them in a barrel and the only way you could find your own is by the serial number.” I can spot my handguns from across the room.