Experts | Ayoob Files |

0

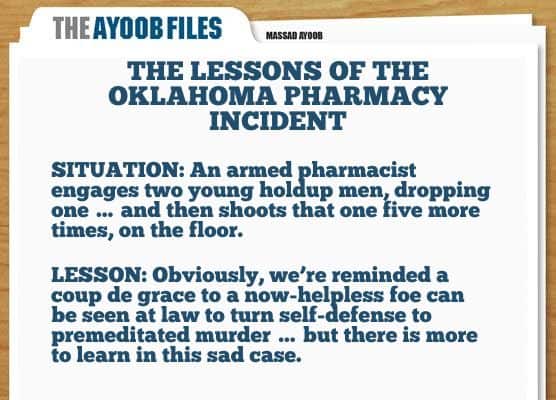

May 19, 2009. Two young men enter the Reliable Pharmacy in Oklahoma City, Okla. One announces a robbery as he waves a gun, the other moves next to him pulling something out of his waistband.

They suffered what I’ve come to call, “a sudden and acute failure of the victim selection process.”

A few steps away from them is a 57-year-old pharmacist who collects guns and knows how to use them. He grabs his Taurus Judge. The hammer rests on an empty chamber in a 5-round cylinder stagger-loaded with a 3-pellet, 00-buckshot .410 shotshell, a .45 Colt cartridge and a different .410 and .45. He fires and one falls. The other, still holding a pistol, runs. Hampered by a body brace, the pharmacist totters after the fleeing gunman, opens fire as the robber and two accomplices take off in a getaway car.

The pharmacist then reenters the store, walking past the first, downed suspect, and goes behind the counter to replace his empty Judge revolver with a fully loaded Kel-Tec P3AT sub-compact auto pistol. He approaches the supine man. Suddenly, the pharmacist raises the little .380 and fires five rapid shots into the man on the floor. Only then does he turn, walk toward the back of the store and call 9-1-1.

He will tell police and reporters, of being an Iraq War veteran who suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder because he killed many enemies in defense of his country, and wears a body brace because his back was broken by enemy fire in Iraq. His name is Jerome Ersland, and will now become one of the most controversial armed citizens of our time.

Jerome Ersland said he fired those last five shots because the downed man was getting up to shoot at him again. Bloodstain evidence showed that Antwun “Speedy” Parker, age 16, never lifted his head from where he fell and died. Ersland said the robbers both had guns, opened fire and wounded him. Only Ersland, evidence showed, never fired a shot and Parker had no gun. It was determined Ersland had never gone to Iraq or been in combat anywhere else, and apparently attempted to fake a gunshot wound on his arm.

The two adult Fagins who drove the getaway car and put two teenagers up to the armed robbery, along with the 14-year-old perpetrator who did have a gun, fell afoul of the felony murder principle: when you commit a felony in which someone dies, it is murder. The two adult males are now serving long prison sentences, the 14 year old — treated at law as a juvenile — will be free in a few years.

Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater charged Ersland with murder in the first degree, on the theory pre-meditation took place in the 46 seconds between when the security camera showed him firing the first shot Prater publicly stated was justifiable, to when he triggered five more shots into the prostrate Parker. Prater made a point of calling a press conference to state he didn’t want to “chill” people’s rights to shoot in self-defense, and even took the extraordinary step of requesting the judge to allow firearms in the drugstore while Ersland, on bail, awaited trial. The judge ruled the pharmacy could have guns present, or Ersland, but not both.

In the early summer of 2011, Jerome Ersland was found guilty of murder in the first degree, and was sentenced to prison. It will be 38 years before he is eligible for parole.

Just as many gun owners judged Jerome Ersland from afar and thought him guilty, there were many of us Monday morning quarterbacks in the criminal justice world who were shocked his attorney presented such a brief defense. The state rested its case after several days of testimony and exhibits, and court adjourned for the day. The following morning, a single witness — a store employee who didn’t see the shooting — testified for the defense, which then rested. Ersland never took the stand.

Ersland’s lawyer, Irven Box, has for many years been considered one of the best criminal defense lawyers in the state of Oklahoma. He was the helmsman who steered the defense, and knew his client better than any of the pundits who criticized him. Therefore, none of us can gainsay the strategy Box used. At the same time, it’s irresistible to explore alternative strategies, which might have been tried.

Self-defense is an affirmative defense, in which the defendant stipulates he did indeed shoot the deceased, but maintains he was correct in doing so. In most jurisdictions, this shifts the burden of proof and requires the defense to show, more likely than not, any reasonable and prudent person would have done exactly what the defendant did. This defense works best when the defendant takes the witness stand and explains what he perceived, what he feared at the time, and why he did what he did. After all, who else can fully explain it better?

It is not hard to understand Box’s decision to keep his client off the stand. Ersland’s wild tales of having killed many in a place where he’d never been didn’t just brand him as a liar and compromise his credibility as to his account of the shooting; it also gave the impression he associated killing people with heroism. And then there were other things obviously proven untrue: Ersland’s statements he’d been shot at and even hit, and his assertion at one point he’d wielded a gun in each hand, and more. All those claims would be demonstrated false to the jury by the prosecution, Box must have known, and would be shown to the jury by juxtaposing his client’s videotaped story to the police, with the security cam videos showing the actual shooting.

Box’s task would be to convince the jury even though his client had falsely described this, that, and the other thing, he was telling the truth about one thing: that Speedy Parker was moving in a threatening manner at the time his client fired that last, fatal volley. If Box felt it would be too great a balancing act with a defendant whose credibility was already profoundly compromised, none of us can really blame him.

Suppose a defense psychiatrist or psychologist had examined Ersland, determined he had something like Munchausen’s Syndrome, and made up heroic exploits for himself because he had a personality disorder, and not in any way to cover up his actions on May 19, 2009? As to the altered sequence of events Erslund described to the police, it wouldn’t have taken a prostitute expert witness spewing psychobabble to give a plausible explanation for that. Disordered memory of the sequence of violent events in a near-death experience, such as having an armed robber point a gun at you or anything as traumatic as having to kill another person, is very common and well documented.

Dr. Alexis Artwohl, one of the world’s most respected authorities in such matters, found confused memory to be an issue for some 21 percent of the many police gunfight survivors she studied. While attorney Box retained two experts to testify as to the stress Ersland would have experienced, apparently neither examined Ersland or submitted reports within the time limits established by Oklahoma’s evidentiary discovery code. Therefore, neither was allowed to testify.

A cornerstone issue in the case was whether or not young Mr. Parker’s head wound caused just enough brain damage that his body couldn’t move in a way a reasonable person might perceive as going for a weapon, but left him still alive with a reasonable prognosis of survival at the time the last flurry of shots was discharged. Neurologists and neurosurgeons tell me people with serious brain damage can still experience spastic, involuntary movements that could mimic someone trying to reach for a weapon.

While the bloodstains near the young man’s head don’t indicate he raised his upper body, that wouldn’t be necessary to present the appearance of a wounded criminal trying to shoot back and get his revenge upon the intended victim who shot him. In the biography of Carlos Hathcock, Marine Sniper by Charles Henderson, there are accounts of enemy soldiers performing such convulsive dances of death even after sustaining lethal brain wounds from high-powered rifles.

District Attorney Prater told me he didn’t think that was likely, since while the Medical Examiner testified Parker’s hands could have twitched or moved, boxes that fell across his right arm were unmoved when the body was photographed by police.

One thing did strike me in watching the tape of Ersland firing those .380 FMJ rounds, which sent him to prison. So we can be on the same page in terms of frame count and time frame, go to YouTube and check out the video. As Ersland approaches Parker, looking down at him, Ersland appears to experience a startle response. His body makes a tiny jump and he appears to suddenly jerk to his left. But there is nowhere to go: a shelf of products blocks him from moving away any farther, and there is no cover.

It is at that point (part of the timeline of the security film is obscured) but you’re looking for the xx.30.xxx area, at about xx.30.737 seconds — the startle response occurs, and it is immediately after that when Ersland is seen to instantly unleash the five rapid .380 rounds.

This is consistent with Ersland’s statement to the police where as he approached to assess the status of the armed robbery suspect he shot down, he perceived the man attempting to rise and shoot him.

A huge number of people have seen this video. Most don’t see that subtle body movement of the startle response because they don’t look for it, and it is human nature to not see what we’re not looking for, nor to look for what we don’t know to look for.

This phenomenon was seen classically when over a period of many years tens of millions of people believed President John F. Kennedy could not have been shot through the neck and Governor John Connally wounded in the chest and wrist areas by the same bullet in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963. It took decades before researchers discovered that on the Zapruder film, the Governor’s lapel can be seen to blow outward exactly where the exit wound was found in his right pectoral area, and his wounded arm flips the hat he was holding violently upward, in the same roughly 1/18th second Kennedy is seen reacting to the neck wound.

Ersland’s jury was apparently convinced he lied about being shot at first. As you review the archived security film of the Ersland/Parker shooting, don’t just watch the one where Parker is seen falling, then shot again subsequently. Look also at the one from the camera at the back of the pharmacy, where Ersland is seen accessing the Taurus Judge, raises it, and fires the first shooting. At about that time, one of the female employees running to hide in the back room is said to have knocked over some bottles from a shelf. Could those bottles crashing to the floor have sounded like gunfire to Ersland, as he looked away from the threat to the gun he was grabbing, the tool of salvation he hoped would save him and the other employees from two criminals threatening their lives with guns?

Ersland was seen as a liar for claiming that both men he shot at had guns, and for believing Parker had one when Ersland shot him with that last fatal volley. But review the tapes again — both the one from the back of the store and the one from the front. You will see suspect Ingram, waving his pistol, is on your right as you watch it, and Parker, pulling his mask out from the front of his waistband area, is on your left. This would put Ingram with the obvious gun on Ersland’s left, and Parker making a movement consistent with reaching for a gun, on Ersland’s right.

At about the time Ersland is retrieving the Taurus Judge, presumably looking down so he can see it to grab it, Parker passes behind Ingram and winds up on our right, with Ingram now on our left. This means that when Ersland saw them again as he came up with the gun, Parker would now be on his left, where he last saw the man pointing the gun in his direction. I submit under these hectic circumstances, this could create the reasonable belief in his mind the man he shot down was a man with a gun, and would give him prudent reason to believe the pistol was still accessible as Parker lay where he fell, after Ersland returned from chasing suspect Ingram to the getaway car.

Analysis of the evidence later indicated no one fired at Ersland, and Antwun Parker didn’t have a gun. But the standard of the law is, “what would a reasonable and prudent person have done, in the exact same situation, knowing what the shooter knew at that time?” Or, as police instructors have been known to say succinctly, “You don’t have to be right; you have to be reasonable.”

Lesson One: Never lie! In my opinion, being caught in a web of lies totally destroyed Jerome Ersland’s credibility and profoundly crippled his defense. There’s a saying to the effect that if you lie once, you’re seen as a liar forever. The truth of that saying was emphatically illustrated in Oklahoma v. Ersland.

Lesson Two: Do not attempt to reconstruct in the immediate aftermath. Ersland discussed the events extensively with police, without counsel present, shortly after the shooting. He reportedly said later he got the sequence of events wrong because of stress and adrenaline. After four decades of intensively debriefing gunfight survivors and more than three of speaking for some of them in court, I’m convinced that’s entirely possible.

We recall that Dr. Artwohl’s research shows memory distortion in some 21 percent of shooting incident participants she studied. Suppose Ersland had simply said, “They came in armed and announced a robbery. I defended my co-workers and myself. I will sign the complaint against this man and his accomplices. Here are the witnesses, there’s the evidence, you’ll have my full cooperation after I’ve spoken with counsel.” Had he left his statements at that, I honestly doubt Ersland would have ended up in prison for life.

Lesson Three: The “coup de grace” is never defensible! This is the most obvious take-away lesson from the incident. It’s presented third down on this particular list only because I’m absolutely sure Ersland lied to investigators about some things … and almost absolutely sure he confused some things. But I’m not absolutely sure from what the public has seen of the evidence that it was an execution instead of a reasonable but mistaken belief that he was facing lethal threat a second time when he fired the last shots from the P3AT.

Lesson Four: Shooting at fleeing felons puts you on thin ice. The citizen’s arrest principle allows armed citizens to pursue violent criminal suspects in many jurisdictions, but that doesn’t make it a smart thing to do. Ersland said he fired at the three surviving suspects because a gun was pointed at him outside the pharmacy, which could certainly justify his use of deadly force.

There was testimony, however, that bystanders were ducking from the buckshot that spun wildly from the rifled barrel of his .410 revolver — not exactly an image of responsibility. The chasing and shooting gave the impression Ersland didn’t think the downed Parker was dangerous enough for him to stay and protect his coworkers, and may have also given the jurors the impression he was particularly eager to shoot someone.

A Google search for Jerome Ersland/Oklahoma City will turn up a substantial amount of discussion and, of course, the three key videotapes from Reliable Pharmacy’s security cameras. It will also bring up at least one website with directions for donating to Jerome Ersland’s legal fund; the appeal of his conviction is underway. It’s safe to say it’s a case that will be discussed in concealed carry classes for many years to come.