Leather Mysteries

Things You Didn’t Know You Didn’t Know

If you are moderately long of tooth, you might remember the classic Laugh-In line uttered by Artie Johnson: “Veerrry intieresstingk…!” I’ll admit I’m that old — older probably, after spending 50-plus years doing leatherwork. I’ve found myself occasionally uttering that very phrase — yes, complete with Artie’s German accent …) as I discover some oddity of historical leather history. So, in no particular order, and at the urging of His Editorship, I present some odd things I’ve learned during my nearly life-long involvement with all things leather.

Whiter Teeth?

The Ancient Romans collected chamber pot “contributions.” Okay, so far. The urine was used for washing laundry, tanning leather and (gag!) — whitening teeth! Nowadays, mercifully, vegetable tanned leather is the standard for holsters. Barks rich in tannin like oak, wattle, mimosa and others, give holster leather its characteristic strength, durability, color and working properties. So, no need to “hold it” to tan your leather these days.

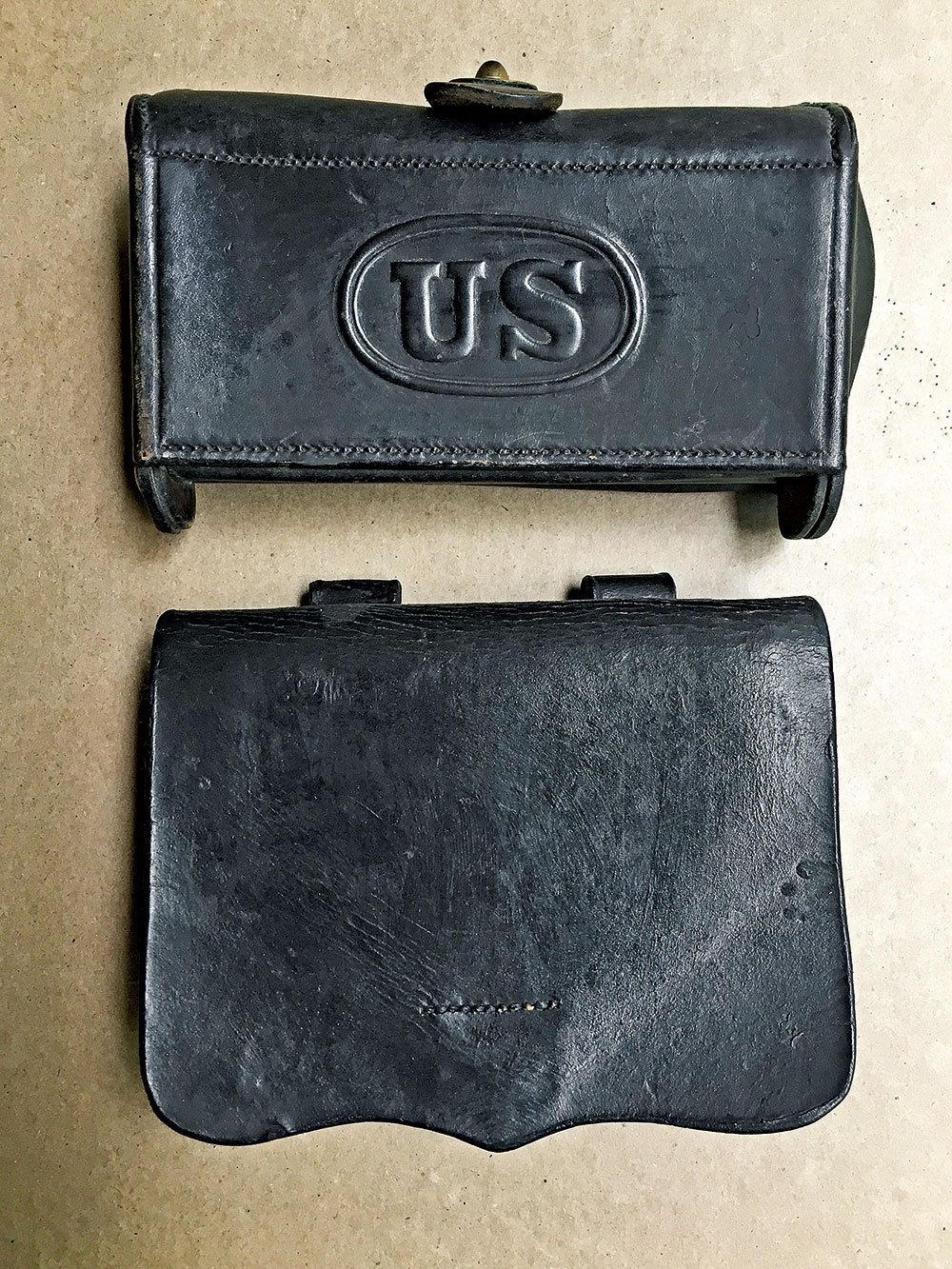

Basic Black

In the 1800s, the U.S. Army specified its black leather be “chestnut oak” tanned because it yielded leather with qualities the military desired, including never bleeding or fading. The interesting part is this super-black leather was never dyed. Yup, that’s a fact. The black color was created through a mad-scientist mix of tannery-specific secret tanning sauces mixed with iron particles. Chemistry basics here — slightly acidic tannin would react with the iron and create a deep black color. How’s that you say? Lay a damp, rusty nail on an oak board and you get the same reaction. Who says we’re smarter these days?

A colleague affiliated with George Lawrence (he of the famous Lawrence Leather Company) told me the classic red-tone of some Lawrence gun leather was not dyed with conventional dyes. A cloak-and-dagger mush of aviation gas (which is red), oils and other fixins’ rendered the color. I can’t verify this but can pretty much say I won’t be trying to duplicate this in my shop to check the veracity of the statement.

Restrictions May Apply

Toward the end of the 1800s, light household sewing machines were easily purchased by anyone who had the cash, but a heavy stitcher used for leather could only be rented. The contract included “mileage restrictions” of 1,000,000 or 1,500,000 stitches per year. The supplier kept track with a complicated-looking “odometer” attached to the hand wheel. When you hit your limit, you were charged by the thousand. The solution? Stitch fewer stitches to the inch to lower the “miles” traveled. This also saved bobbin thread changes, increasing production, making the bean counters happy! Some things never change, eh?

In those days, sewing machine companies held incredible monopolies. If their reps found even a single machine made by someone else on your factory floor, they yanked all their stuff out and you were stuck. The Union Shoe Machinery was actually taken to the Supreme Court over this. Rentals continued up until the late ’60s when the sudden rush of saddlemakers and harness makers running away to parts unknown with “rented” machines made purchasing outright de rigueur.

The current standard for machine or hand stitching by the majority of custom leather guys runs seven to eight stitches per inch depending on the item. The old U.S. Army standard was seven, eight or 10 stitches per inch, again depending on the item.

The Queen’s Royal Standard is 13 stitches per inch — hand-stitched, by god! I remember standing absolutely slack-jawed staring at the beautiful fine stitching on Queen Victoria’s personal side saddle at an exhibit once. It still makes my heart flutter just thinking about it! Yeah, I don’t have much of a life.

No Lining Please

Most old holsters were stitched, but not lined. This was about price, yes, but mostly because linings couldn’t be installed easily or permanently until readily available contact cements became commonplace. So how did craftsmen hold leather pieces together for stitching back before all the sticky stuff? Ordinary shoe tacks. Do the words “cobbled together” ring any bells?

Original Synthetics

Technology also marched forward in other places. Remember Gutta Percha grips? Those were made from a prehistoric rubber of sorts. It was turned into everything from hot water bottles and buttons to ponchos and holsters. The holsters were tried experimentally during the Civil War and were a dismal failure. But grips worked just fine. So whatever happened to Gutta Percha? Ever get a root canal? Hmm, am I saying your dentist still uses Gutta Percha? Yup.

Synthetics were also being tinkered with by the Germans. An ersatz leather called Prestoff, made of laminated paper, gained its widest use through WWII in everything from holsters and belts to horse tack. The unfortunate part is the fact it would delaminate if it got soggy or if repeatedly flexed. Consequently, the Wehrmacht issued a lot of real leather to their line troops and the second-line folks got the pressed paper stuff.

This gear also took on a certain obvious smell with “mileage.” Really good U.S. sergeants and lieutenants taught their men to sniff out Germans by this particular odor — literally saving the lives of their troops with their noses. Kinda makes you wonder if the Germans trained their guys to sniff out that wet-dog smell well-used American web gear made? “Fritz! Shhhhhhh! — sniff, sniff — Vebbing! Das sind Amerikaner!”

Veerrry intieresstingk…!