Big Bore Snubbies

Good Idea or Waste of Time?

The concept of bigbore, snub-nosed revolvers isn’t new. In fact it’s just about as old as revolvers themselves. As soon as men began to carry revolving cylinder handguns they began to follow two paths. Some wanted them to be concealable and some wanted them to shoot big bullets. Some tried to mate the two paths and they discovered they don’t necessarily go hand in hand.

One problem is the greatest bulk, as in detriment to concealment, comes with a revolver’s cylinder. And also along those lines the bigger the bullet a revolver shoots, the thicker the cylinder. Consider this: I’ve carried both full-sized Colt 1911 .45 Autos and Colt .45 SAAs in inside the belt holsters. The .45 Auto is perfectly comfortable. The .45 SAA feels like you have a cantaloupe inside your belt.

Also barrel length is a critical factor in revolver power because longer barrels burn powder more efficiently, giving more velocity. Snub-nosed barrels throw that burning powder out into space in the form of muzzle flash, which of course means bullets are going slower. Regardless, Americans traditionally have favored big handgun bullets.

Beginning Ideas

One of the most prominent characters in American Old West history who combined the concepts of big bore bullets with snub-nosed revolvers was an El Paso city marshal named Dallas Stoudenmire. He had the 8″ barrel of a Colt .44 caliber “factory conversion” cut to about 3″ and then packed it in a leather-lined hip pocket. In my research I’ve not been able to discover if Stoudenmire actually used that revolver in any of his several gunfights but he did manage to get himself killed in a drunken shootout after being fired from his marshal’s position.

In the “1st Generation” (1873-1941) of SAA production Colt would make bigbore snubbies on special order. They came in whatever barrel length the buyer specified. I’ve seen them as short as 2″ but by the “2nd Generation (1956-1974) and “3rd Generation” (1976-current) Colt cataloged them as “Sheriff’s Models.” Universally they had 3″ barrels sans any provision for ejector rods. Caliber options have been .44 Special, .44 WCF (.44-40) and .45 Colt. Some were made in sets with both .44 Special and .44 WCF cylinders.

Over the years I acquired one of those dual cylinder, .44 caliber, Colt SAA Sheriff’s Models. Back in the 1990s I had a custom gunsmith make me a facsimile of Stoudenmire’s .44 Colt conversion but with one important difference. Because it is of open top design the barrel can be switched in a minute, so I had it fitted with two barrels. One is 3″ long and the other is the standard 8″.

Modern Versions

Starting in the 1980s the large sporting goods distributor Lew Horton began prevailing upon Smith & Wesson to build sizeable runs of revolvers exclusively for them. Many of those special-run Smith & Wessons have been big N-frame .44 Specials and .44 Magnums with 3″ barrels. The only one I’ve personally owned was a .44 Special. It was the Model 24 with round butt and adjustable sights. It was a nifty gun but still very bulky.

And that brings us to 2010. When his Exalted Eminence Roy and I began discussing this article he suggested we contact Smith & Wesson’s Performance Center to see what they had going in bigbore snub-guns.

Sure enough Smith & Wesson currently has three bigbore snubbies in production. They are the Models 627, 657 and 629 meaning, in the same order, they’re chambered for .357, .41 and .44 Magnums. At first glance I thought all three models were identical, but they’re not. The .41s and .44s are six-shooters but the .357s are 8-shooters.

All are stainless steel with round butts, 2.75″ barrels and checkered walnut grips. Rear sights are fully adjustable, but a nicer touch is the front sights are inserts installed in a ramp. The benefit of that is all adjustment doesn’t have to be done with the rear sight. Drifting the blade in its dovetail can do the rough adjustment and then the rear can be fine tuned in relation to the exact load being used.

Another little feature on these three big bore snubbies I like is the triggers are smooth. Such guns as these are primarily meant for double action shooting. Because they will deliver rather substantial recoil, a grooved trigger will likely peel hide off the shooter’s trigger finger. For those who would prefer single action cocking, the hammer is nicely checkered. Coming from the Performance Center their trigger pulls were expected to be nice and they were. My scale won’t measure DA trigger pulls but their single-action pulls were all in the four pound range give or take a few ounces.

Chart of Velocity Differences by Barrel Length

Weight And Performance

We gun’riters are always hammered about not saying anything bad about products, and with some magazines that’s a valid complaint. His Editorial Immenseness doesn’t dictate anything to us about that either way, so here goes. A bigbore snub-nosed revolver is going to be bulky and heavy enough, so why equip one with a non-fluted cylinder? These things weigh about 2½ pounds. Cut some weight off — please. Otherwise they are great little/big guns. And I understand about marketing and the “cool” factor, but it just makes them heavy!

Now, if you’re still following me, you have got to be asking yourself, “What does a 2.75″ or 3″ barrel on a bigbore revolver cost you in performance?” And if you hadn’t asked yourself, you should have. In regards to basic inherent accuracy it doesn’t cost much, if anything. I put the .41 Magnum in my machine rest and got sub-3″ groups at 25 yards. Not great but not bad either. In my opinion barrels will differ more individually in regards to accuracy than they will because of lengths. What does suffer, is the shooter’s ability to actually hit with them because of reduced sight radius. A short handgun is simply harder to hit with than a longer barreled one — with all other factors equal.

As for the velocity question, I fired these three S&W bigbore snubbies alongside with long barreled revolvers of the same calibers with the same loads on the same day. The little chart I’ve included shows the velocity differences. I also shot a pair of .44-40s just for fun.

In a nutshell velocity loss can vary from inconsequential to extreme. The key factor is what the ammunition is meant to do in the first place. If it’s meant to deliver high velocity it was likely loaded at the factory with slow burning propellants. If it was meant for modest velocities then it was likely loaded with faster burning propellants. With the former powders reducing barrel length will greatly reduce velocity but with the latter types not so much will be lost.

I’ll point out a single example of each. Going from a 6.5″ .357 Magnum barrel to a 2.75″ one with Black Hills’ 158-gr. lead “cowboy” loads meant a reduction of only 39 fps. However going from a 7.5″ .41 Magnum barrel to a 2.75″ one with Speer’s 210-gr. JHP load meant a loss of 307 fps. I did find the short barrels to be very loud with fullbore magnum loads with corresponding heavy recoil.

These two got His Editorship started thinking about putting Duke onto a bigbore

snubby article. At top is a 1917 S&W .45 ACP Roy cut down about 20 years ago

and below is his cut-down Charter Bulldog .44 Special that rode in an ankle

holster for many years during his police career. Both have home-done Parker-

izing jobs. He likes short-barreled bigbores.

A Good Idea?

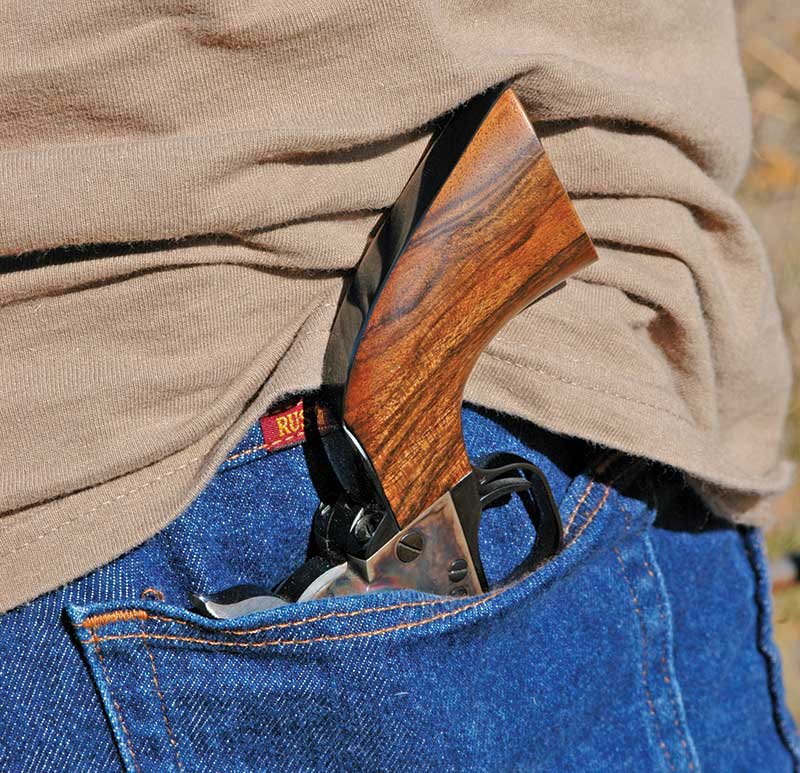

So what’s the bottom line on bigbore snubbies? My opinion is they have their place, but it’s not so much in carrying them as in stashing them. For instance, carrying a 4″ N-frame Smith & Wesson on your person wouldn’t be significantly more difficult than carrying a 2.75″ one. That extra 1.25″ of pipe sticking out isn’t a great hindrance. That said, I do stick my Colt SAA Sheriff’s Model .44 in my hip pocket here on my Montana property during rattlesnake season. It carries five chambers full of shot loads.

Where I do see a place for bigbore snubbies is in secreting them in a hidy-hole such as a console in a vehicle, if you’re allowed to do such a thing, a book shelf, desk drawer or other such place. Their bulk isn’t a factor there, and their stubbiness could be a boon. The concept of snub-nosed, bigbore revolvers isn’t the greatest idea to come down the pike, but it does have its niche.