Jack Weaver:

The Real Weaver Stance

In the beginning was point shooting. For those precious few who prepared themselves to use a pistol as a serious defensive weapon, it was fired from the hip, without the benefit of sights. For others, including target shooters and law enforcement officers alike, the pistol was fired at arm’s length, onehanded, and, often, very slowly. Either way, the pistol was a one-handed gun, and the unfortunate thing was neither the close-quick-dirty approach nor formal pistolcraft bore any real resemblance to the skills needed to survive a real-life shooting. And then in 1959, along came an L.A. County Sheriff’s Deputy who held his pistol with both hands, hit what he aimed at, and did it faster than anyone else. His name was Jack Weaver, and as Jeff Cooper put it, “He showed us the way.”

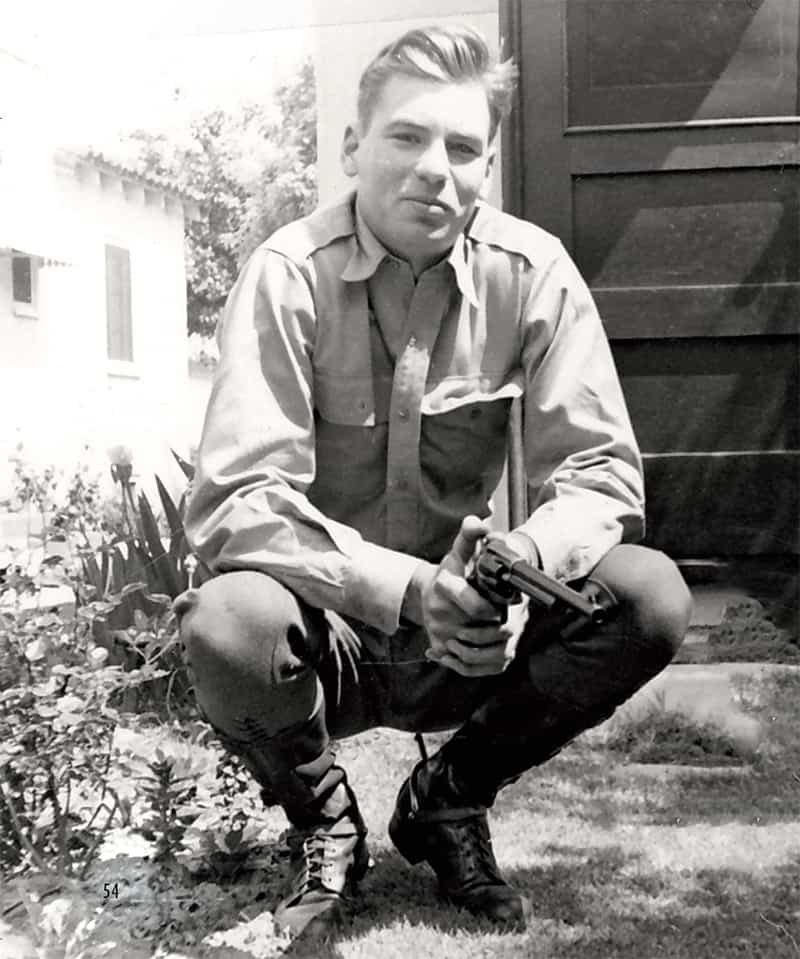

Jack, an only child of only children, was born in Huntington Park, California, where his father worked for the Matson steamship line. From a young age, he loved guns. In his own words, “When I was a kid, real young, I mean like about 10 or so, I was fascinated by revolvers. Not the automatic, but just the revolver. Something about the cylinder with the holes in there.” Like most of us, though, he actually started shooting with a .22 rifle. In Jack’s case, it was a teenaged relative’s gun, which was always accompanied by a nail with its head cut off. After each shot, you had to drop the nail down the barrel to knock out the empty shell.

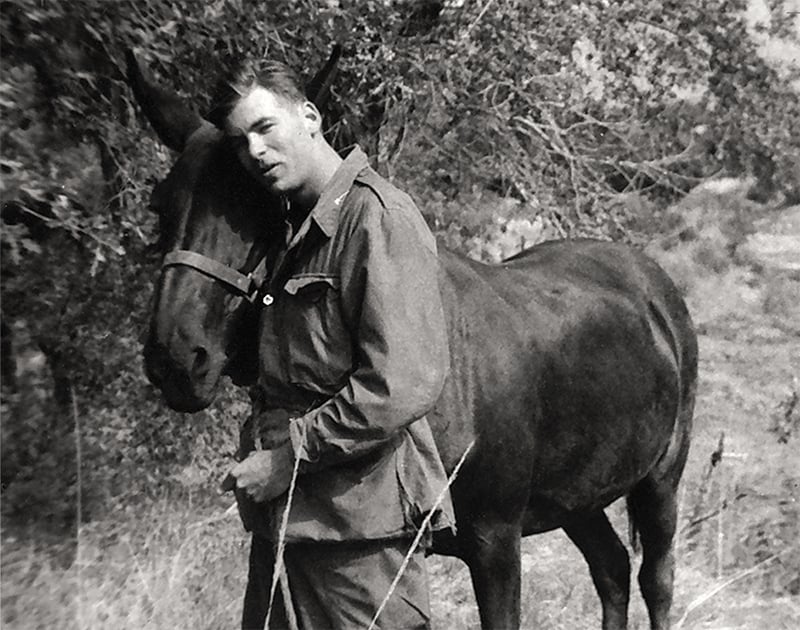

After graduating from high school, he attended Glendale Community College, where he met Joy Moniot, whom he would later marry. She was studying airline administration, and he was taking mostly machine shop, until he was drafted into the US Army in 1950. Although it was during the Korean War, Weaver was stationed at Fort Carson in Colorado, where he served in 4th Field Artillery, Battalion PK — and that’s “PK” for “Pack.”

Also known as the “Mule Pack,” Jack’s unit cared for and trained with the 400-some mules used to transport 75mm Howitzers over rough terrain. It took seven mules to carry one gun, and they hauled them up and down the Colorado mountains (including Pike’s Peak), often for weeks at a time. Although Jack got in by volunteering (“I didn’t know exactly what it was!”), he easily met the basic requirement that you had to be over six feet tall. And the anachronism of being in the mule pack was not lost on him. Still dating Joy, who worked at the Texas Oil Company in L.A., on one occasion he visited her at work in his uniform, complete with riding breeches and high leather boots. As Joy put it, “They thought he was somebody impersonating somebody.”

A Really Good Gun

It was in 1952, near the end of his tour, when Jack bought what he describes as his first really good gun, a Smith & Wesson K-22. “As soon as I held it in my hand, I knew I was going to be good with it.” The same year, he married Joy, who moved to Colorado to be with him, and they spent the last few months of his military service living in a mountaintop cabin in Cripple Creek, a true outpost that came complete with wooden water pipes.

After moving back to Glendale in the brief interval between military and law enforcement, Jack was doing heavy construction work on a highway project when Joy got word one Friday he had been hired by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office. In those days before cellphones, she got a ride to the construction site and left a note on his car telling him to quit so he could start work as a deputy on Monday.

Their first few years there were quiet. They moved from Glendale to Lancaster, some 75 miles outside of L.A. proper. There, their three sons Alan, Mark and Garry, were born. In his off time, Jack, a self-described “desert rat,” took full advantage of the nearby terrain, and the family spent their holidays wandering the hinterlands in his Ford Model A, camping and exploring the many old ghost towns that waited silently in the desert. But I’m getting ahead of the story.

The Leatherslap

What we know now as practical shooting began in 1956, during the Old Miners Days festival in Big Bear, California. Held every August, the event played up the Wild West theme, with lots of townspeople walking around in period dress and whatnot. Some folks went all out. Jack actually watched one fellow in a string tie walk into a public men’s room and shave with a straight razor.

As part of the festivities — and as a promotion for the Snow Summit ski resort — the then-little-known Jeff Cooper organized the First Annual Leatherslap “quick draw” contest. With the TV airwaves overflowing with Westerns, quick draw was something of a sport in and of itself, with trick shooters doing all sorts of amazing things with blanks and timers and other gimcracks. Always practically minded, however, Cooper wanted the contest to replicate what would happen in an actual gunfight.

When he was in Quantico, Virginia, where he’d first begun his serious study of the pistol, Cooper had seen the FBI’s Duel contest, which pitted two men against one another in shooting electrically-charged targets that popped up as the men walked toward them. Cooper’s variant, omitting the electronic timers he disliked, was a true mano a mano — two men standing side-by-side, waiting for a signal, when they would blast away at 18″ balloons placed seven yards away. Whoever hit theirs first won, and whichever shooter got three hits first advanced to the next stage. As Cooper put it, you “Beat your opponent, not the clock.” Pistols had to be chambered for at least .38 Special and there were no other rules. No major or minor calibers, no holster or hardware restrictions. Whatever was fast, won.

The problem was that fast wasn’t all and hitting mattered, too. As it turned out, many of the competitors were lightning-fast at missing, and the spectators were treated to a few stages of both competitors blazing away, only to run dry, clicking their guns at the targets still swaying gently in the breeze. If balloons could laugh, they were doing it. In fact, Cooper’s 1958 Guns & Ammo article summing up the first few Leatherslap duels bore the subtitle: “A tradition of the West is a fast-growing sport today — but unless you can hit your target it’s no good.”

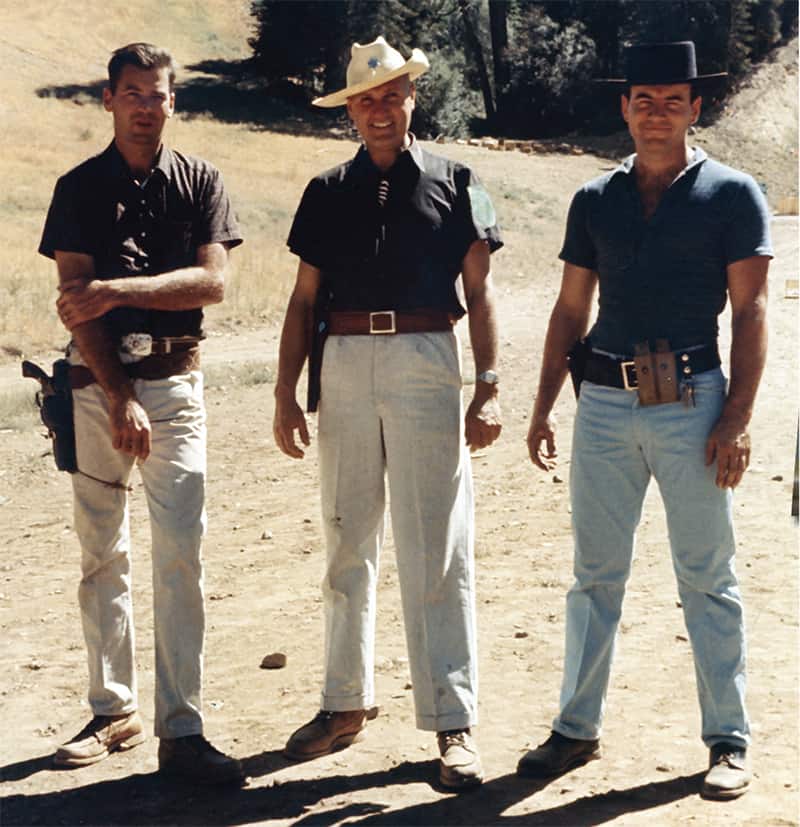

All this aside, it was a great show, and people loved it. Jack, however, had heard nothing of it until he saw a flier for the second annual on the bulletin board at the Sheriff’s Office, and decided to give it a shot. In keeping with the spirit of the thing — as well as the overall zeitgeist of the quick draw craze — many Leatherslap competitors (such as Thell Reed, whom Cooper named “The Master of the Peacemaker”) shot Single Action Army revolvers. A few progressives, such as Jeff Cooper, plowed ahead with M1911 autos. But Jack, bracketed on either side by singleaction Colt .45s, used a 6″ Smith & Wesson K-38, which he fired doubleaction, and used to shoot his way to second place. “It was just a fluke,” he says, “I was as bad as the rest of them.”

Practice

Determined to win the next time, he spent a year practicing a technique where he brought both hands together at waist height — essentially, a two-handed version of the Fairbairn & Sykes “half-hip” and “three-quarter hip” point-shooting technique — where the pistol was brought to the vertical centerline of the body and then fired. Jack was eliminated immediately, and had another year to think about it.

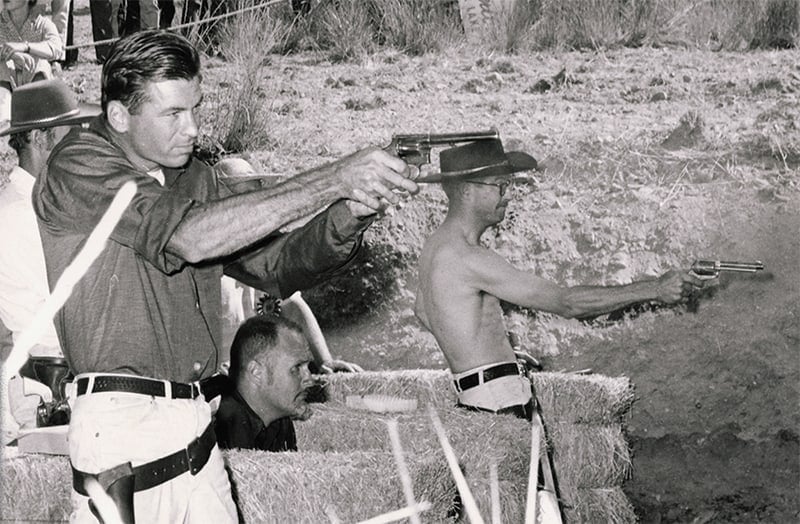

During this year of practice, however, he realized if he brought the pistol up a foot higher, and dropped his head just a bit, he could get a split-second look at his sights before pulling the trigger. Thus was born the Weaver Stance: two hands on the gun, with a flash sight picture and the offside foot placed a little forward. So in 1959, the trophy marked “Leatherslapping: Best Overall Gunfighter” went home with Jack H. Weaver’s name engraved on it. What made his win so sensational was no one had ever seen a pistol shot like Weaver was shooting his. “It looked kind of stupid,” he concedes. “Everybody was laughing at me, but it worked. I took the money.” Laugh though they might, he had found something that worked, and it worked consistently.

“They’re a stubborn bunch,” Jack says of the early combat shooters. “They kept laughing at me and thinking it was funny, and I thought, ‘that’s great!’” It got to the point the Weavers could get a hotel room and buy dinner, and count on paying for it with the winnings. After being beaten three years in a row, Jeff Cooper gave some careful thought to Weaver’s shooting position, finally announcing it was “Decisively superior” to anything else.

From his bully pulpit writing for Guns & Ammo, Cooper described the matches and the lessons learned, ultimately distilling them into the Modern Technique of the Pistol that formed the backbone of his teaching. In 1987, when Cooper was interviewed in Handgunner, he stated “Most of what I’ve done in my life has been eclectic — taking the best ideas of other people and putting them to use.” True to form, though he popularized it and taught it, he always gave Jack Weaver the credit for the stance. Indeed, it was Cooper who named it the “Weaver Stance.”

Evolution

The matches themselves evolved as well: the group that began as the “Bear Valley Gunslingers,” became the “South West Combat Pistol League,” and, ultimately, the International Practical Shooting Confederation, and then USPSA. In the meantime, Weaver was made the range officer for the Sheriff’s Department’s 8-target Mira Loma range, a post he’d hold until retirement.

From the very beginning, the matches were a family affair. Jack and Joy attended their first shoot with a three-week old Mark in tow, and, in the most famous photo of Weaver winning the ’59 Leatherslap, you can see Jack’s father among the spectators, hunched over, intently watching his performance. And it wasn’t just the Weavers; Jeff Cooper’s wife Janelle and their three daughters attended regularly. After the shooting was over, there was usually a barbecue of some sort. “It was a good group that always got together,” Joy says, “It was all just a real nice thing to plan on.”

Jack stepped quietly away from competitive shooting in 1972, when it all got too complicated. What had begun as a group of families shooting and enjoying each other’s company had evolved into an incorporated, rules-bound thing without much of the charm with which it had begun. Retiring from the Sheriff ’s Department in 1979, Jack moved from Lancaster to the Carson City, Nevada, area. With his characteristic tongue-in-cheek sense of humor, when he left, he hung a sign at the department range reading “Jack H. Weaver Memorial Firing Range.” It stayed there until the wind blew it down — it was the only recognition the department ever gave him.

Where’d Jack Go?

And so time passed. Jack got a letter from the FBI National academy in 1982, letting him know they had adopted the Weaver stance. The Weaver Stance became the Modified Weaver, and became a part of the Modern Technique of the Pistol, as set forth in the Gregory Morrison book of the same title. Cooper, of course, went on to found Gunsite Academy, where the Weaver Stance remains part of their core doctrine. There’s even a framed photo of Jack Weaver hanging on the wall in the main classroom, alongside portraits of Thell Reed, Elden Carl, Ray Chapman and Bruce Nelson, all shooting from the Weaver stance. Gunwriters still never tire of arguing Weaver vs. Isoceles, although the Weaver is now so universal it even popped up by name in the movie Meet the Fokkers. While the stance became a part of the culture, the man behind it was almost forgotten — almost.

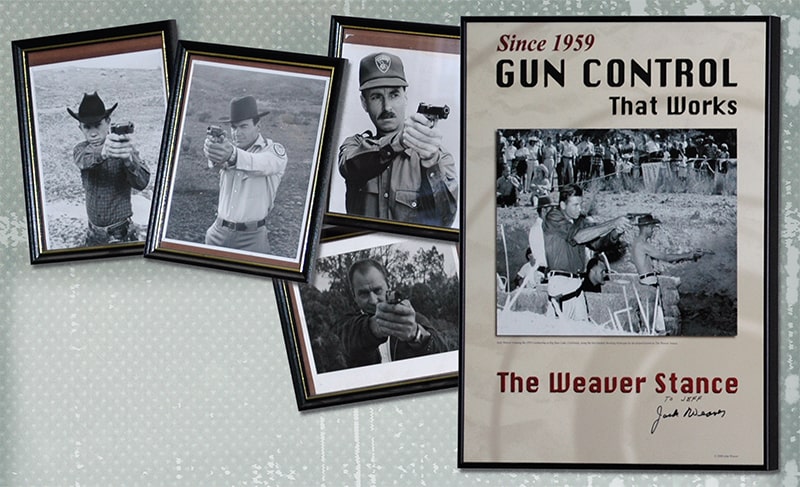

Wanting to see his father’s legacy remembered while he was still alive, his oldest son Alan created posters showing Jack winning the 1959 Leatherslap, shooting from that famous position. Across the top was the legend: “Since 1959 Gun Control That Works: The Weaver Stance.” Offering these signed by his father, Alan created a Web site. Doing some research one day, that Web site was discovered by Handgunner editor Roy Huntington. He, in turn, forwarded the link to me with the simple instructions: “Find Jack, visit him, and let’s get him the credit he’s due. There’s one heck of a story here, and we’re going to do it.”

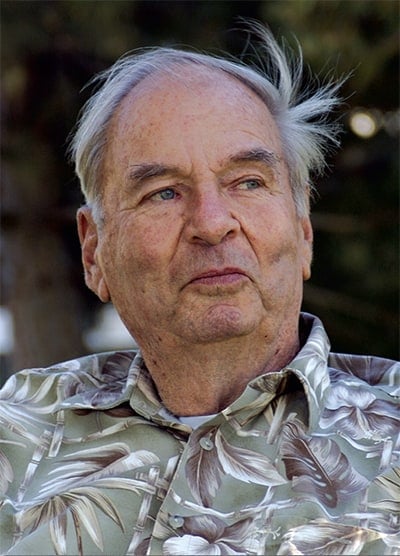

After I spoke with Alan over the phone, Jack Weaver called me and graciously agreed to let me come interview him face-to-face. And so, after a few weeks of reading Cooper’s books and getting my questions together, his wife Joy and their middle son Mark — just retired from law enforcement himself — met me at the Reno airport and drove me to the Weaver home.

The Real Jack Weaver

Spurred on by his finds exploring ghost towns, Jack developed an interest in antique bottle collecting, and their living room shows it. A lighted cabinet holds some of the rarer ones, and row upon row of them stand at attention on their high shelf near the room’s cathedral ceiling. These are not liquor bottles; most are from the quack remedies and nostrums so popular in the late 19th century. Marked with names like “Congress Water” and “Stomach Bitters” and with logos such as a man throwing away his crutch, many of them are handmade.

A credenza holds still more bottles, standing in ranks, along with other memorabilia, such as coins he found in the desert, and a British Commando dagger — designed by Fairbairn and Sykes — its blade gleaming in the afternoon light. His spurs from the Mule Pack sit next to one of Jeff Cooper’s books. Near the end of the room, a cast iron wood burning stove sits on its brick base, with a row of rifles, shining in walnut and well cared for bluing, leaning against the wall by the cabinet that fills the corner. On top of the cabinet sit two nickel slot machines, a 1922 Jennings and a 1934 Mills. The Jennings came from the Matsonian, one of the ships upon which Jack’s father had worked. Jack had painstakingly rebuilt both of them, and a small tub of nickels sits between them (play all you want, but leave the winnings, please).

On the opposite wall hangs more of Jack’s handiwork, in the form of two blackpowder .44 revolvers he built from kits; their well-polished octagonal barrels look almost liquid when the flats catch the light. Two gunbelts — one of them an Andy Anderson, his favorite holstermaker — hang next to them, as well as several more revolvers, including the US marked 1879 Colt SAA he used in the Leatherslap, its brother from 1890, and a brace of percussion .36s. His Star progressive reloader sits under a desk, a marvel of machining and design that has loaded countless thousands of .38 and .45 rounds.

Jack takes the time to tell me the stories when I ask about each of these things, and to pull out old photos. We talk about the men he shot with in the early days: John Plähn, who was a fellow deputy and Mark Weaver’s 8th grade Government teacher; Thell Reed, the teenage prodigy who now teaches sixgun work in Hollywood; Elden Carl, the perfectionist who was the most competitive with Weaver; Ray Chapman, who now teaches the Modified Weaver; and, of course, the late Jeff Cooper. “If it wasn’t for him, I don’t know what would have happened,” Jack says. “He always gave me credit.” Joy agrees: “Because of Jeff Cooper, is why it went on to anything.”

During my time with Jack, he shows me several of his revolvers: a S&W K-22 Masterpiece like the one he bought in the Army, his carry pistol — a J-frame Smith with a bobbed hammer — and one of his famous 6″ K-38s. Stock, except for having the serrations removed from its trigger face. Its action is smooth as butter, and Jack handles the pistol with the familiarity only arriving after many years, and countless rounds fired. While he experimented with both 4″ and even 8″ S&Ws, he found he didn’t shoot as well with the shorter as he did with the 6″, and he did no better with the longer gun. Thus is the very simple reason he’s known for shooting 6″ Smiths.

Like many of us who appreciate the aesthetics of things, Jack feels modern pistols have lost much of their visual appeal. “To me, a pistol is a thing of beauty,” he tells me. “And you’ve got to really love the thing before you can shoot with it.”

Although Cooper had read books such as Fast and Fancy Revolver Shooting by Ed McGivern and Shooting to Live by Fairbairn and Sykes, Jack had no such external influences. When we talk about the stance itself, he begins by describing the two-handed hip shooting posture that led him to it. “I came up with bringing up the gun and grabbing it with the other hand,” he explains. “I thought the two hands would kind of zero it in at the same position every time. It worked pretty good, in practice, but during the contest I got shot down the first time, so I thought, ‘Well, that didn’t work.’”

Then, he continues, he realized “If I raised the gun up just about a foot higher and tilted my head down a little bit, I could see the sights. It was just as fast, and I thought I had something. I did that for a whole year, and I got to where I could hit the target each time.” Looking at the sights also let him practice with an empty gun. Dry-firing from the hip gets you nowhere, because you can’t see where your shot would have gone. “Sure enough,” he continues, “I won. Wiped them all out.” As the matches expanded beyond the original quick draw format, Jack found his system “Worked better on all those than it did at the Leatherslap, really.” The other competitors, of course, first laughed and then began taking notes, unsure about what they were really seeing.

It Doesn’t Look Right

The Sheriff’s Department, in particular, didn’t know what to think. Jack recalls how his supervisor, who made an every-Wednesday visit to the range, was stymied. “‘I don’t know about this two-handed stuff, Weaver,’” Jack remembers him saying. “‘It just doesn’t look right to me.’” He often reminded Jack that N.R.A. rules required one-handed shooting. Jack responded they didn’t have any one-armed deputies. “They used to make fun of me, ‘Quick Draw Weaver,’ as if it was a big joke,” he says, “Well, they carry those guns, they’re not just for shooting bullseyes.”

And when I ask Mrs. Weaver what she thinks about the whole thing, she responds in kind. “I’m very proud of him,” she tells me, then pauses. “You know, I think he’s saved many lives, and I’ve heard that from other people … that’s pretty amazing.”

In his Book of Five Rings, Japanese swordsman Miyamoto Musashi directed his readers “To maintain the combat stance in everyday life and to make your everyday stance your combat stance.” For the serious minded among us, this is one of the great strengths of the Weaver stance. Having your offside foot slightly forward (which cops will immediately recognize as the “interview position,”) puts you in the position to respond to a threat with whatever force is required. Whether that involves throwing a punch, using an ASP baton, or drawing a pistol, you’re already in the right position.

As Ed Head, Gunsite’s Director of Operations, put it, the modern version of the Weaver is a “balanced fighting stance,” and Gunsite teaches it across all the weapons platforms, including pistol, rifle, shotgun and SMG. When we talked about its attributes, Head focused on the fact the Weaver allows movement and weapon retention, as well as excellent recoil control, all of which are part and parcel of defensive shooting. “You don’t have to be big and powerful,” he explained, “The technique is what it’s all about.” And there’s no doubt these advantages of the Weaver stance — its universality, speed, retention and recoil control — have saved the lives of many law enforcement officers.

Jack Weaver explains the shooting stance named after him

to American Handgunner’s Jeremy Clough

Pretty Close — Every Time

Before we finish, I asked Jack if there are any misconceptions about the stance he’d like to clear up. “The idea it has to be done a certain way,” he tells me, explaining that much of it is about “what’s comfortable.” I ask him to show me how it ought to be done, and, pistols in hand, we step outside into the back yard.

“Figure out where your target is,” he tells me first. Standing next to him, I watch as he lines his feet up, the left a little forward of the right, and takes his two-handed grip on the pistol, with his left hand wrapped around the right, unlike the “teacup,” and “wrist grab” holds used by some others. A man with large hands, Jack wraps the thumb of his left over the top of his right hand, just out of range of the K-38’s hammer, then quickly cautions me not to do that with the .45 auto I’m holding.

“Your eye, the back sight, front sight, and the target don’t have to be perfectly lined up,” he says, bending his head down slightly and bringing the gun up to eye level, “but you can see the sights, and as you squeeze the trigger, you correct them as best you can. Pretty soon, you get to the point where you come pretty close every time.”

I watch closely, and try to imitate his movements as he brings the gun up to eye level and strokes the trigger through, dry-firing. “If your feet don’t feel right,” he tells me, “you just pick them up.” I ask him if I’m doing the Weaver Stance right, and he hands me his K-38, so I can try it with a revolver. He watches me bring the gun up, then tells me, “If you find something that works better for you, why, go for it.”

Special thanks to Chris Coulter, PhD, Nathan Tippins and the Weaver family.

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: