The “Navy” term didn’t come because the US Navy adopted the model; it came because the roll-engraved scene on its cylinder depicted a naval battle. The scene showed a battle that took place in the Gulf of Mexico on May 16, 1843, between ships of the navies of the Republic of Texas and Mexico. The “Navy” term became so synonymous with the belt pistol it became commonly called “Colt’s Navy” and .36 was often simply referred to as “Navy caliber.”

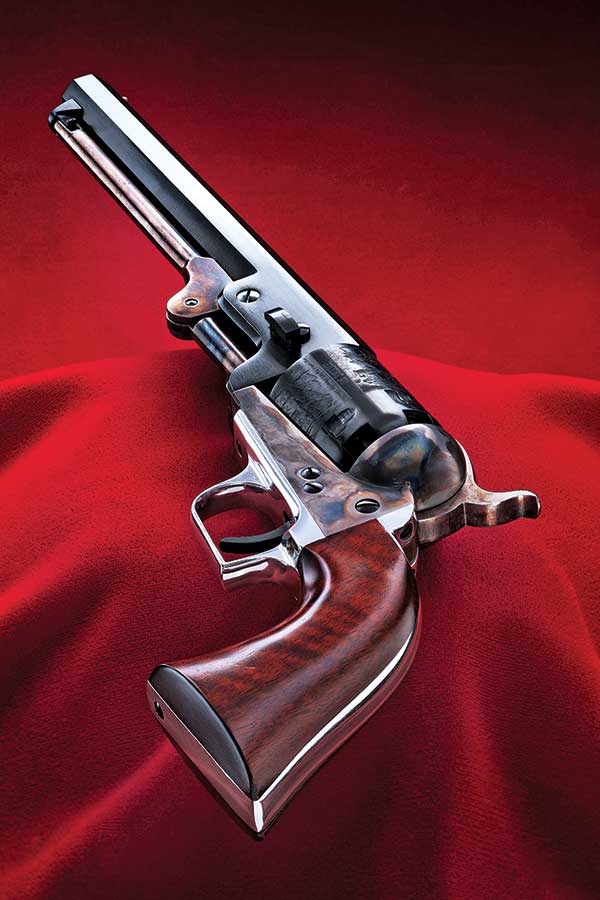

Sam Colt gladly accepted custom orders so original belt pistols can be found in a wide variety of finishes and barrel lengths. Yet the quintessential Navy Colt had a 7½" octagonal barrel, blued barrel and cylinder, color case-hardened frame, hammer and loading lever and a grip frame of nickel-plated brass. Grips were 1-piece wood, but many Navy Colts wore custom ivory grips. Early ones had a square back triggerguard. Shortly into production, that was changed to a roomier oval type. Weight was only about 2½ pounds, making it perfectly feasible to wear on a belt and quickly accessible when needed. Of course, the mode of fire was single-action-only.

The First Gunfighter's Sixgun

Colt's 1851 "Navy"

The era of The American gunfighter of fact and legend didn’t begin until 1850. That was when Samuel Colt introduced his first “Belt Pistol” meaning one practical for a man to actually wear on his person in a holster. Prior to that, Colt revolvers came in two types; the big military .44s weighing over four pounds and meant for packing in saddle holsters, or small .31-caliber “pocket pistols” intended for civilian self-defense and concealed carry. Consider this: before about 1850 one of the most famous Old West figures was Jim Bowie, the famous knife fighter. After that time most famous Old West personages were gunfighters.

Today, commonly called Model 1851 Navy, Sam Colt’s belt pistol actually appeared the year before. Its frame was a new medium-sized one. Its .36 caliber was between the .31 and .44 sizes, previously offered by Colt. Worthy of note is in the era of percussion revolvers caliber was denoted by the barrel’s bore size and not its groove diameter. Hence the new Colt was termed .36 caliber when the proper ball size for it was actually .375″.

Stopping Power?

Until the advent of the Colt Navy, personal altercations were settled with knives. The victor was usually the strongest and largest antagonist. Sam Colt helped equal the odds because then quarrelers could stand apart and shoot it out. Large size only made for a bigger target. Reflexes and gun handling ability counted more, with of course eyesight being a factor too. Colt percussion revolvers of all types wore the most basic of sighting equipment though — a notch in the hammer with a bare nub of a front sight.

By today’s standards Navy Colts had rather puny “knock-down” power. Projectiles for them came in two forms, either a round ball or conical bullet, weighing about 80 and 140 grains respectively. From a 7½” barrel, black powder propelled them at about 1,000 fps for the ball and 750 for the bullet. In terms of foot-pounds of energy (not that it matters) they landed roughly between modern .32 and .380 autos, which is about the right way to think of the .36. Think of firing an 85-grain .380 at around 900 to 1,000 fps and you’ll get an idea of what a Colt Navy had on-board.

However, only pure lead was used for bullet alloy so wounds were often severe, especially if bones were hit. Furthermore, balls often lodged in a victim’s bodies causing complications such as infection. It has been written that famous outlaw Jesse James took a .36-caliber ball to his body as a guerilla fighter during the Civil War and carried it until his death in 1882.

Although the Colt firm sold “cartridges” — paper ones holding a black powder charge and one of the two types of projectile — they also sold powder flasks and bullet moulds. Powder flasks wore spouts made to measure out the amount of black powder fitting into the 1851’s chambers, leaving enough room to seat the ball or bullet on top. It was also a good idea to seal the top of the chamber with some sort of soft grease. That kept moisture out and also helped stop flashover, which was when flame from the shot being fired leaked into adjacent chambers so that all let go simultaneously. It happened in the old days, and still happens today with this sort of revolver if you’re not careful.

Above: The Colt Model 1851s didn’t get the Navy nickname because of an adoption by naval forces.

It came from the naval scene roll-engraved on the cylinder. Below: This powder flask is marked for the

Colt Navy and its spout is adjustable for the proper black powder charges for both conical bullets and

round balls.

As a final step the percussion cap goes on the chambers’ nipples, making the revolver ready to fire. Back in the era when men carried percussion handguns into all sorts of weather they sometimes dripped candle wax over the percussion caps so they were sealed from moisture.

Speaking of weather, in the beginning of the pistol-packing era, the most common holster was the military flap type with a piece of leather covering the top of the handgun to protect it from rain, snow, mud, hard knocks and debris. When gunfighting became a factor, pistol-packers cut away the flap so as to make the revolver more accessible. While all this was evolving, so was the California gold rush of the 1850s. Even today, “boom towns” are rough places so carrying revolvers in California mining camps became standard adornment. Those were mostly Navy Colts with 7½” barrels so their holsters were long and slender. Today those holsters are known as Slim Jim or California holsters.

Gunfighters

There’s a common misconception that whenever a new development was introduced in handguns in the mid-1800s, gunfighter types jumped right on them. For example when Colt’s 1860 Army .44 appeared you might think gun-toters discarded their Navy Colts for the bigger caliber. Some may have, but the .36s stayed popular. They were lighter and didn’t have the exaggerated grip frame of the newer design. The same reason people carry small autos or revolvers today — because they’re handy, not necessarily because they’re very effective. Besides, immediately after the Model 1860’s advent, Civil War demands took most of the Colt factory’s production. As late as the 1870s, some dedicated gunmen preferred their Colt Navy sixguns even after metallic cartridge handguns were for sale.

Perhaps the most famous of those was Wild Bill Hickok who used his brace of Colt Navy .36s when serving as city marshal for Hays, Kan. in the early 1870s. Wild Bill became the most famous “pistolero” of his era and will forever be identified with Colt’s Navy revolver because he was photographed with a brace of fancy, ivory-stocked ones.

During its 22 years of manufacture about a quarter million Colt Navy revolvers were made, both at the company’s Hartford factory and at a short-lived London plant. Today Model 1851s are either very valuable or in pitiful condition. I’m not going to shoot either type. However, in the 1970s and spilling over briefly into the 1980s, Colt Firearms once again offered Model 1851s made of new steels and usually exhibiting quite good workmanship. There are many rumors of exactly who made these guns but that doesn’t concern us here.

A Cased Set

I just happen to have a brand new unfired sample of that newer Colt series in a cased set, with powder flask and bullet mould, and it’s a wonderful looking kit. Originals were often sold in just such sets. To start with, bullets were cast in the little brass mould that came with the set. It was cut for both round ball and conical bullet. Molten pure lead was ladled into it, and brothers and sisters I can assure you gloves will be needed with that thing. Only a few pours were made before it got hot, and by the time 60 projectiles were made (30 of each style) I couldn’t hold onto it any longer — even with heavy leatherwork gloves. I can’t imagine Wild Bill casting his own .36 Navy lead balls on some fair damsel’s cook stove.

The powder flask in my cased set is labeled “Colt Navy.” The spout has two settings: one for the longer conical bullets and one for round balls. That latter setting dropped 24 grains of Swiss FFFg black powder. Swiss brand was chosen because it’s the hottest on today’s market. That much powder just allowed the pure lead balls to seat below flush in the chambers. After all six were powdered and balled some lard was spread atop each. Then the percussion caps were seated and the revolver was ready for firing.

Let me add this, my 60-plus-year-old fingers are getting slightly arthritic; all the small motor skills needed to load that thing are far more difficult now than when I got my first cap-and-ball sixgun in 1967! Something else changed are my eyes. The sights on the Navy Colt were just a blur, so the 5-shot groups fired at 25 yards were all 4″ to 5″ in size. My 1851 was centered for windage but impacted about a foot above point-of-aim. That meant it was about “on” at 100 yards. In fact I did manage to hit an Action Target’s PT Torso steel plate twice out of a cylinder-full at that range. The chronograph said the 80-grain balls were going 974 fps on average.

Many handguns favored by fighting men came later: Colt SAAs and New Services, S&W N-frame .44s, the .357 Magnum and perhaps the top dog of all, the many 1911 .45s. But the gunfighter’s beginning was with Colt’s 1851 Navy .36.

Subscribe To American Handgunner

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: