DIY Bullets: You Can Use Cast Bullets in Semi-autos

Something irking me now for over a half-century is someone saying, “My pistol needs jacketed bullets.” That attitude is especially wrong in the middle of this component shortage, the likes of which have not been experienced in the United States since World War II. At worst, some modern semi-autos with their non-conventional barrel rifling are instructed by the accompanying booklet not to shoot cast bullets. A simple solution would be to purchase a drop-in barrel with normal rifling.

However, the best scenario is most semi-autos digest cast bullets exceptionally well. A few can be recalcitrant, which will be discussed shortly. I have successfully and quite easily handloaded cast bullets for semi-autos chambered for a baker’s dozen autoloader cartridges ranging from .30 Luger to .45 Auto. In between are some oddballs such as 7.62×25 Tokarev, 7.65mm French Long and 8mm Japanese Nambu.

My only difficulties came with perhaps the most popular semi-auto caliber worldwide — 9mm Parabellum aka 9mm Luger. A great deal of my 9mm Luger shooting has been with military pistols of World War I and World War II vintage. My theory is that due to wartime emergencies, tolerances of some manufacturers were relaxed a mite as in 9mm Luger barrels being cut slightly oversize.

My first experience using cast bullets sized at the nominal 0.355″ (typical for jacketed bullets) resulted in tumbling bullets. Upping their diameters to 0.356″ helped and .0357″ bullets are even better. As an experiment one time, I cast some gas check 9mm bullets from a long discontinued RCBS mold. Sized to 0.357″, they shot nicely. Still, I’ll be darned if I’ll fumble with gas checks for the numbers of bullets I’d think sufficient.

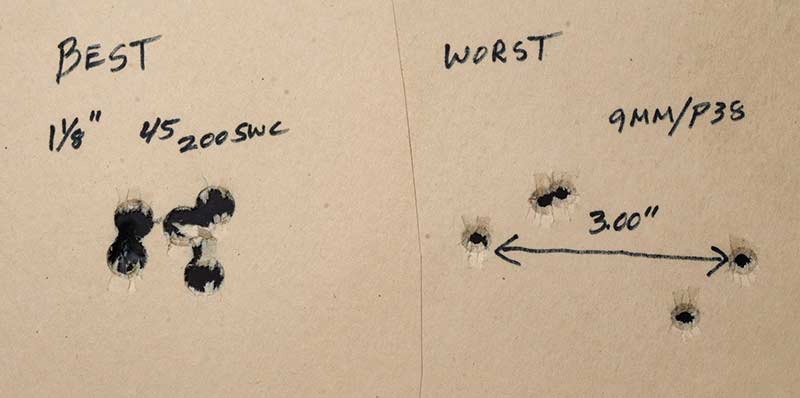

However, the crowning achievement of my 9mm Luger cast bullet shooting came with some of Missouri Bullet Company’s coated 0.356″ round noses. Fired from a machine rest, my 1943 vintage German P38 printed groups of 3″ and under. This is one of the few times I’ll admit to commercially cast bullets leaving my home cast ones in their dust. In fact, during one afternoon from machine rest, I shot MBC’s coated cast bullets in 9mm, .38 Super, .40 S&W and .45 Auto, and nary one of them failed to shoot nicely. Pistols used in the same order were the P38, a Colt 1911 ELCEN Model .38 Super, a Kimber Pro-Compact and Les Baer Thunder Ranch Special 1911.

This affirmation that coated bullets are good doesn’t mean conventional lubed bullets are bad. Much of my .45 Auto handloading has been with Oregon Trail’s 230-grain roundnose. My M1 Thompson submachine gun functions fine with that bullet. Also, I have a 1918 vintage Colt Model 1911. At 103 years old, I hesitate to put undue stress and wear on it with full-power jacketed bullet loads. To ensure jacketed bullets do not stick in barrels, they should be loaded to at least 800 fps. For my old 1911, a charge of 4.5 grains of IMR Trail Boss powder gives about 730 to 740 fps and serves the pistol perfectly. Some readers are saying, “Duke is getting loopy in his old age. Trail Boss is meant for light loads in large capacity cases.” It is true you will likely not find a load for Trail Boss in .45 Auto in published reloading manuals. However, it is listed for .45 Auto on Hodgdon’s Load Data website.

Top Cast Bullet Tips

Perhaps the three most important factors in shooting cast bullets in autoloading pistols are as follows:

First: Be sure the bullet is at least 0.001″ over barrel groove diameter, and 0.002″ is no problem as long as that diameter doesn’t swell cases to the point they won’t chamber. That’s more of a possibility with tight chambered commercial pistols than vintage military issue ones.

Second: Choose the shape of your bullets wisely. Mostly that means round nose (RN) or round nose/flat point (RN/FP). This may not be a stumbling block at all with some civilian 9mms. I once bought an S&W Model 39 but had no proper bullets. In a froth to try it out, I loaded some cast .357 semiwadcutters of 150 grains, of course, with a corresponding reduction in my Bullseye powder charge. They fired perfectly from that 9mm and were more accurate than the cast RN bullet design finally purchased for it.

Third: In handloading, make sure bullets are securely locked in cases. If they are not and the rather hard passage from pistol magazine to chamber pushes a bullet deeper into the case, pressures can increase dramatically. Although I have successfully gotten away with carefully roll-crimping bullets in .45 Autos, I don’t recommend it. It is far easier and safer to get a taper crimp die or one of Lee’s Factory Crimp Dies.

Hardness

When someone is first delving into handloading cast bullets, they will quickly find almost all commercially available ones are of hard alloy. While I don’t agree non-Magnum revolver bullets should be so hard, ones for semi-autos need be. Again, it is the matter of transitioning from magazine to chamber. Softer bullets are “grabby.” Hard bullets are slick. Missouri Bullet Company puts the Brinell Hardness Number (BHN) of their cast bullets on the package. Those meant for cowboy action type target loads have a BHN of 12, but those meant for semi-autos are rated at 18 BHN.

A friend gave me enough straight Linotype to last the rest of my life. Its rated BHN is 22. My semi-auto bullets are all poured of it, sized to 0.001″ over barrel groove diameter and lubed with either SPG or DGL lubricants. Those are primarily black powder lubes, but I’ve found them excellent with smokeless powders. However, be forewarned they can be messy if bullets are jumbled about. That’s the reason commercial bullet casters prefer hard lubes.

Ideal Bullet Weight

Here’s a tip about choosing the proper bullet weight for your semi-autos. If you are shooting a standard off-the-shelf pistol with fixed sights, then bullets weighing at or at least approximating standard factory load bullet weight are best. The reasoning for this statement is firearms manufacturers put fixed sights on their pistols for that weight. Heavier bullets will print higher at typical pistol shooting distances and lighter bullets will impact lower.

Despite 9mm Luger factory load bullets ranging from about 100 to 147 grains, I’d bet factory sights are regulated with factory loads using 115- and 124-grain jacketed bullets. Those bullet weights are most popular among 9mm shooters. Therefore, when loading 9mm Luger with cast bullets, I’ve used 115- and 124-grain Missouri Company RNs and 124-grain Oregon Trail RNs. Those cast by me are 120-grain RNs from Lyman mold #356242.

Final Tips

Now I’m going to give a few tips many years of cast bullet shooting have taught me. Look for versatility in cast bullets. For instance, I stock 0.401″ cast RN/FP bullets of about 170 to 180 grains for my many .38-40 Colt revolvers. Those same bullets are perfect for loading in .40 S&W and 10mm Auto. (The reverse is not true because bullets seated in .38-40 cases need a roll crimp to secure them, and 40 S&W/10mm cast bullet designs have no crimping grooves.)

Another example of versatility is RCBS’ RN/FP bullet #45-230CM. It was intended for .45 S&W/.45 Colt use in cowboy action matches. It is a satisfactory cast bullet for .45 Auto and functions perfectly even in my Thompson. There’s a new cartridge introduced in 2022 named .30 Super Carry. I read its nominal bullet diameter is 0.313″ and factory loads carry 100-grain JHP bullets. I have a mold for 105-grain cast RN/FP bullets intended for .32-20 revolvers. It drops 0.314″ bullets, which I suspect would be perfect for the new cartridge in the unlikely event I end up with a pistol for it.

If you want to shoot your semi-autos plenty, especially in this day and age, don’t sneer at the cast bullet option. I keep bullet molds on the shelves for every handgun owned so there will never be a shortage at Duke’s Place.

This article merely scratches the surface. I recommend one of Lyman’s Cast Bullet Handbooks for those interested in more information. I can proudly state that I was listed as the primary author in the 4th Edition.