Better Shooting:

Curing the Flinch

How to Exorcize the Flinch Demon

Flinching is the most common and potentially most damaging shooting fault. Flinching is an involuntary reaction to pressing the trigger — a reaction to the muzzle blast and recoil. Humans have natural reflexes to protect against danger. One is the blink reflex to protect the eyes against sudden movement which might threaten the eyes. Another is an involuntary reaction to a sudden loud noise.

Flinch impact

Flinching is not the same thing as poor or mediocre trigger control. A novice shooter can have poor trigger control without flinching and, through regular training, can advance to acceptable trigger management. But even superlative shooters can flinch on occasion. In fact, some top shooters refuse to even use the term, just as some pro golfers refuse to use the word “choke,” fearing using or even thinking of the word may summon the demon.

The result of an all-out flinch can be wondrous to behold. I’ve seen flinches so bad the bullet dug up dirt halfway to the target, even when the target is only 10 to 15 yards away. Many a handgunner in a defensive situation has missed his target at a range of just a few feet. It is easy to criticize such misses but add a flinch to the enormous stress of a life-and-death situation, and one can understand.

Exorcising The Demon

The first step in curing a flinch is to recognize it exists. Many shooters are unaware they flinch or deny it indignantly, as though they had been accused of swindling orphans and widows. The best way to identify a flinch is an exercise called “ball and dummy.” The shooter fires at a target on the range without knowing if the firearm is loaded. One way is for a companion to hand you the firearm, sometimes loaded and sometimes not.

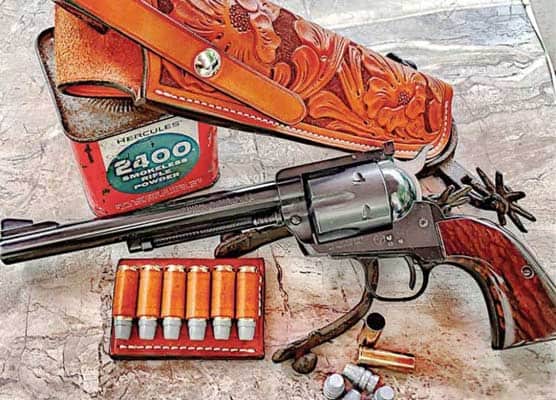

Another way, if you don’t have a companion available, is to reload dummy cartridges with no powder and a dead primer and mix them with your regular practice ammunition. When the firing pin drops on an empty chamber or dud round, any tendency to flinch will be glaringly obvious. I’ve seen shooters try this with powerful centerfire rifles and practically fall on their faces when the rifle clicks. Obviously, you don’t want these dud cartridges to get inadvertently mixed in with your competition or defense ammunition.

The surest way to develop a flinch is with a loud, powerful, hard-kicking handgun. Some seem to find it hilariously funny to hand a novice shooter a very powerful firearm and video the result. A predictable result is we lose a potential handgun enthusiast. Those who pull such stunts should, in my view, be Tasered until they permanently lose bladder control.

Curing the Flinch

To avoid or cure a flinch, the basic rule is to never let the gun hurt you. Firearm reports lead to flinching and permanent hearing loss, so always use hearing protection. Modern ear protectors are very good for the most part; I especially like electronic muffs so range commands can be heard. It isn’t foolish to double up with both foam ear canal plugs and ear muffs.

Limit the level of recoil. A new hand- gunner will progress fastest with a .22 LR using regular speed ammunition. I appreciate many new shooters are primarily interested in personal defense and don’t want to buy more than one handgun. Such shooters are best served with a medium-sized handgun chambered for medium cartridges such as 9mm Luger and .38 Special. I think a 9mm or .38 weighing around 30 oz. is about right. Leave the ultralights and big bores for later, after you’ve learned to shoot.

“Blinking” is the mildest and least harmful type of flinching. Blinking is shutting the eyes at the exact instant the gun fires. It happens so quickly most people are unaware of it. Blinking can often be seen with TV and movie actors when the camera angle shows the shooter’s face as the gun is being fired. It happens so often you can practically count on it. I believe all shooters blink occasionally; some blink all the time. Most are blissfully unaware of it as the blink happens so quickly. The best way to detect it is with a video camera set downrange on a tripod and focused on the shooter’s face.

Blinking won’t hurt your shooting, but unless you see what is happening when the shot is fired, it is hard to improve. The best cure is by dry fire; replace the bad habit with the good habit of keeping the eyes open while shooting. When you can “see the flame” when actually shooting, you’ve beaten the blinking habit.