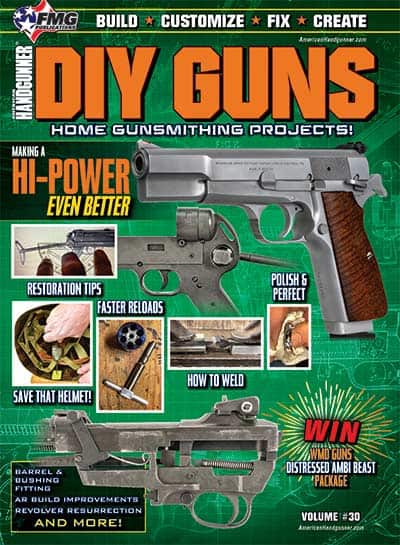

Sights, Bites And Grip

A Field Guide to the Custom BHP

With a long-enjoyed reputation for outstanding reliability and ergonomics, the Browning Hi-Power (BHP) needs only limited work to make it a superb defensive pistol. Like anything else, though, the end result depends on the platform with which you begin, and some Hi-Powers make better base guns than others.

The first consideration is historical value: Some guns are just better left alone. The Hi-Power was always intended as a military pistol (hence the French army requirement it have that silly magazine safety that keeps the mag from dropping free), so there’s a mix of military and civilian pistols on the market. Military guns are the ones likely to have collector value. Some people take a perverse pleasure in modifying extremely rare guns for reasons I’m not sure I fully understand, but, like a ’64-½ Mustang, a pistol is only original once. Even if you don’t value the history, sell it to someone who does, buy a cheaper base gun and pocket the excess.

Changes Over Time

Mechanically, there have been few changes through the 87 years the BHP has been around. The first-generation pistols (including the wartime Canadian Inglis guns made starting 1944 with the help of BHP co-designer Dieudonné Saive) have internal extractors, á la M1911, and use an interesting oval sear pivot insert in the side of the slide to retain the sear lever that connects the trigger to the hammer/sear. Several changes were suggested in 1962. These include a simple roll pin to hold in the sear lever and a pivoting coil-spring-powered side extractor generally considered more reliable. Earlier guns also have a vestigial semicircular divot on the forward right part of the slide intended to make it easier to push in the end of the slidestop when field stripping the gun. This was also omitted to simplify manufacture but has no real effect on the gun’s usefulness.

Another oft-unsung mechanical change is the 1989 introduction of a firing pin safety. Appropriated by FN but invented by Wil Hauptoff of Devel, the firing pin safety is brilliant in its simplicity. Rather than add any new parts (other than a tiny coil spring), the sear lever is widened to create a paddle to interfere with a forward firing pin movement. That’s all there is to it, unlike the various complex multi-part assemblies added to M1911s through the generations.

Forged and Cast Frames

Hi-Power frames were traditionally forged, except the wartime Inglis pistols, which were made from billets. However, this changed to casting contemporaneous with the introduction of the .40-caliber Hi-Power in 1994 — instantly recognizable because of its heavier reinforced slide. I love the Hi-Power, and though it’s falling out of favor, I like the ballistics of the .40 S&W much more than the 9mm. These two are not, however, a match made in heaven. The change in weight and the much sharper recoil changes the vaunted handling characteristics of the Hi-Power, making it more ungainly. Your mileage may vary, but I prefer the Hi-Power in 9mm.

Forged and cast frames are also easy to tell apart due to the grooves on the bottom of cast frames whereas forged frames are left smooth. Either is functional, but the added hardness of the cast frame is a little more difficult to texture. Less commonly found are aluminum-framed lightweight guns. If you can’t tell when you pick it up, you’ll know after taking the slide off. Alloy frames can be modified just like steel ones but will need to be re-anodized afterward.

Safety Improvements

Because there are fewer aftermarket parts available for the M1911, the Hi-Power tends to draw a certain creativity out of gunsmiths. Take for example, safeties: The original one is a tiny, flat grooved rectangle that may be even harder to hit than the early pre-A1 M1911 safety tab. Later, MkII and MkIII pistols have extended safety levers with a right-side lever to make them ambidextrous. Since it was not always so, gunsmiths often made their own by welding or silver brazing on material to shape into an extended contact pad and sometimes even making those into one-off ambi safeties.

Ahh … Old Sights

As you’d expect of a near-90-year-old service pistol, early Hi-Power sights are typically lousy, and even the later white rectangle sights have their shortcomings. The Inglis has a bulbous integral sight base that would have to be removed before adding an aftermarket sight to be aesthetically pleasing, but, like the tangent-sighted pistols with their optimistic range markings, should probably be left alone due to its historical value. I’ve seen Hi-Powers by Kings Gun Works and Swenson with K-Frame S&W sights installed, and while cool, these are very much of their era. There are far better options now, and modern Hi-Powers are more likely to have a high-profile fixed rear by Heinie or Novak, with my preference being the Novak sight.

No Biting!

Besides the frustrating magazine safety (whose only virtue is how easy it is to remove), the Hi-Power’s worst vice is hammer bite. Like the M1911, it tends to pinch the web of the hand between the hammer and the receiver tang and is fully capable of drawing blood. Hi-Powers have either spur or rowel “Commander” style hammers: Both bite. I used to think the Commander hammers didn’t, but I’ve earned the scab to prove they do since then. As with the safeties, gunsmiths have been creative in how they’ve solved this problem, with some focusing on the frame and others on the hammer. Unlike the M1911, there’s no easily swappable grip safety, so adding a beavertail to the frame to protect the shooting hand means welding or brazing on additional material and shaping it by hand. Very cool, very expensive and likely a task beyond most of our abilities.

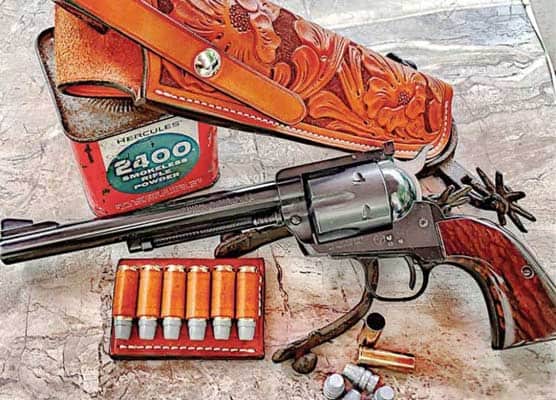

Modifying the hammer is significantly less involved. On rowel hammers, the bottom of the ring is cut away, leaving the hole open on the bottom so it will clear the hand, but with enough of the upper surface left to cock easily, a solution also seen on early Detonics CombatMaster .45s. Spur hammers can be shortened and relieved on the underside (as shown on the Girsan pistol in this issue of DIY), which removes the portion of the hammer most likely to contact the top of the hand. For the more enthusiastic among us, one of the Devel Hi-Powers had its hammer cut to the profile of the slide. Svelte, but you’re never thumb cocking it again.

Slick Grip

We all know smooth pistols are hard to hang on to, and there’s a lot of slick real estate on the front and backstrap of a Hi-Power. Unfortunately, that real estate is quite thin, which rules out the 20-, 25- or 30-line-per-inch checkering usually found on the M1911. It would break through the frontstrap, creating an expensive, visually interesting paperweight.

Many years ago, I had the privilege of reintroducing Lee Jurras to the Hi-Power Armand Swenson had built for him and that pistol had been carefully checkered front and rear at an impossibly fine 40 lines per inch. It is extremely difficult to do well and extremely time-consuming. As a hobbyist working for yourself, you can lavish more time on such a project, whereas a professional would have a hard time charging enough to make it worth their time.

Some early bullseye pistol frames were sandblasted to give them texture, and that’s an option worth considering. Others were stippled, which is frequently seen on Hi-Powers. Matting is a hand-applied texturing process that was a trademark for first Armand Swenson and then Wayne Novak, who worked for Swenson. Novak taught me the process. Stippling instructions and punches are easy to find, but matting remains a distinctive technique for which you’ll need to send the gun to Novak’s.

My thoughts on what I want a Hi-Power to look like are found in the Girsan article. But what to start with? If I wanted to use an FN/Browning gun, the MkIIIS (well after the switch to a side extractor) with a forged frame and firing pin safety would be my choice.

For those wanting more information, there are fewer books on the Hi-Power than on the M1911. Still, two will do: Blake Stevens’ The Browning High Power Automatic Pistol published by Collector Grade Publications and Stephen A. Camp’s The Shooter’s Guide to the Browning Hi-Power. The first is the last word on historical information, while the Camp book is excellent for end users.