The Unfriendly Skies

Personal Defense Strategies For Airline Travel

The tragic events of September 11, 2001 changed our lives forever. One aspect that has changed most dramatically has been air travel and the security processes and procedures associated with it.

Having been a frequent business traveler for many years, I can clearly remember the days when it was easy for anyone to go through security to pick up or see off friends and family. I also remember when traveling with a pocketknife — not to mention a full-sized tube of toothpaste — was no big deal.

Although the tedious security process has definitely taken some of the fun out of traveling, I am glad it’s in place and I am confident the process — despite its flaws — helps keep us all safer. However, at the same time, I still cringe every time I have to pack my knives into my checked bags and walk onto a plane unarmed. Why? Because if a bad guy wants to get a weapon on an airplane, he’ll find a way. And, since the rest of us play by the rules, he’ll be the only one with the weapon.

We Are On Our Own

If you think this is paranoid, the next time you travel, take the time to get some food on the “other” side of the security apparatus. If you can get a glimpse of the kitchen, you’ll notice that it looks like any other kitchen — full of hardworking folks making minimum wage. It’s also full of the “tools of the trade,” which include things like big, sharp chef’s knives. The exact details of how one of these knives could get into the hands of someone boarding a plane are not difficult to imagine — and I’d rather not give the bad guys any ideas — so we’ll leave it at that. Suffice to say, the situation is plausible and the threat of someone getting aboard an aircraft with a serious weapon is still very real. What does that really mean? It means we’re on our own.

Let’s face it, if a terrorist (or anyone else, but for ease of reference, we’ll stick with “terrorist”) cooks off on an airplane, the people in the cabin will most likely have to fend for themselves. Yes, it’s possible there might be an Air Marshal aboard the flight. If so, you’re very fortunate and he will be the best equipped and best trained to deal with the situation. Unfortunately, flights with Air Marshals aboard are the exception rather than the rule.

If the flight is piloted by an FFDO (Federal Flight Deck Officer, a.k.a. “armed pilot”), the harsh truth is that his job is not to save you or engage the terrorist; it’s to defend the cockpit and prevent the plane from being used as a missile. He’s not going to open the cockpit door to rescue you.

Similarly, although I’ve met some flight attendants whose demeanor certainly convinced me they had the capacity to kill, I doubt they actually have the physical skills to take on an armed terrorist. Surly only goes so far, so they’re not going to save you either.

Once again, the inescapable truth is: you’re on your own. So with that in mind, let’s take a look at the finer points of close combat on an airplane.

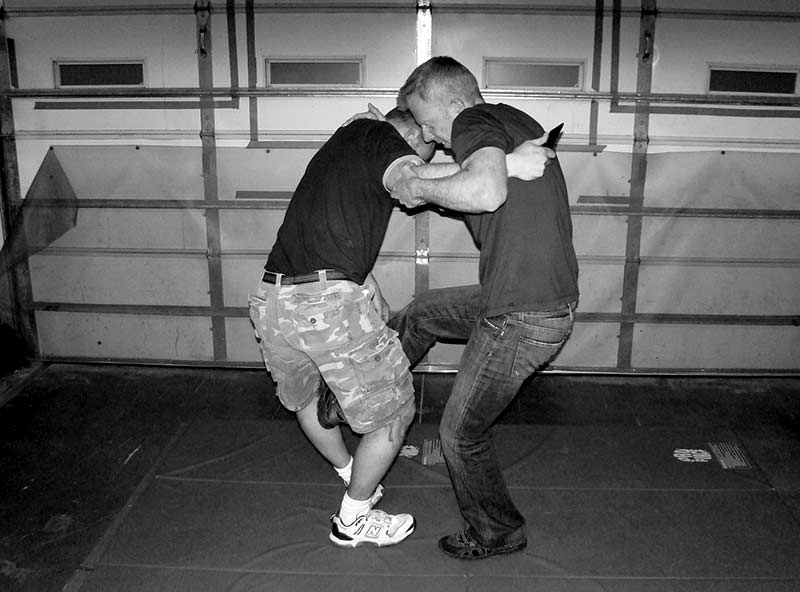

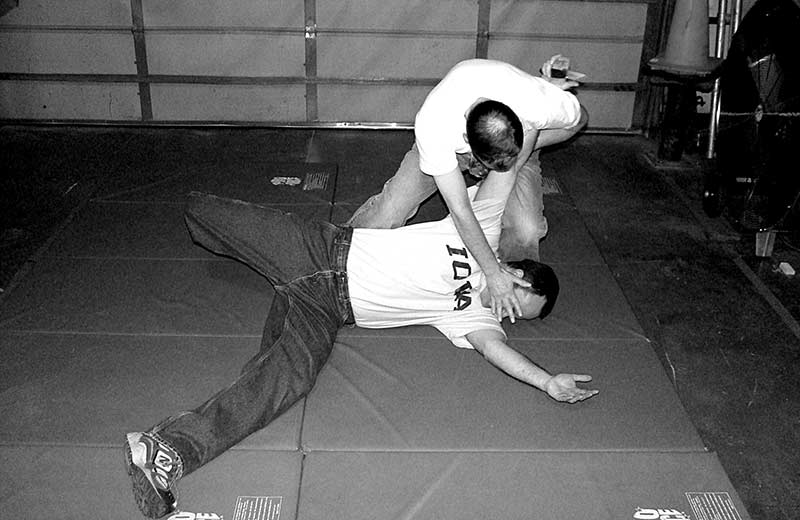

Close Quarters:

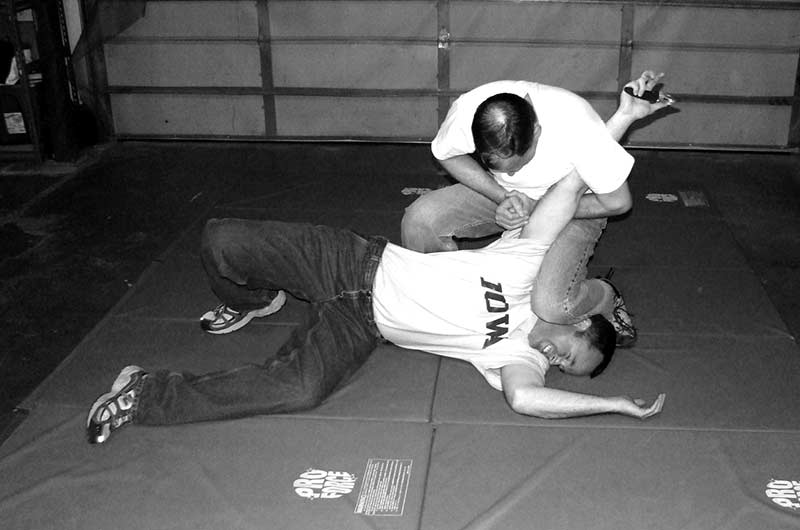

In contrast, this sequence shows an effective defense for confined quarters. After the initial block and elbow strike, the defender drives a hard, straight knee to the groin, followed by a stomp to the knee. Driving straight ahead into the attacker’s space, the defender follows him to the ground, pins the knife arm with his left foot, and executes follow-up strikes to finish the job.

Rule #1: Pick Your Fights

First of all, we need to define what we’re really talking about. If someone on a plane does something clearly threatening the safety of the other passengers, the crew, and the aircraft itself, your life is in danger. If you are convinced of that fact and feel the person must be stopped to keep you and the other passengers safe, it’s time to act.

If the guy in the seat behind you had too many drinks and is being belligerent, as tempting as it may be, you can’t beat him unconscious and claim it was in the name of national security (no matter how tempting that idea may be).

Rule #2: When It’s Time To Act, Go Big Or Go Home

Anyone willing to attack other passengers or threaten to take over an airplane is well beyond the point of reason. He’s also beyond the point of wristlocks, submission holds, pressure points, or any other control-oriented tactics. As such, your approach to stopping him (always the ultimate goal) should be breaking him to take away his ability to harm others. Although knocking him unconscious would be nice, crippling the body parts that make him dangerous to you might be easier — at least initially. Instead of arm bar, think “arm break” and you’re on the right track.

Rule #3: Have A Weapon

Fighting empty handed should be a last resort. Whenever possible, use a weapon to stack the odds in your favor. I know, you’re thinking “I can’t have a weapon because I had to go through security.” Well, just like beauty, weapons are in the eye of the beholder.

One source of weapons aboard an aircraft is the parts of the aircraft itself. To be more specific, I consider seat cushions the easiest “go-to” weapons available to the individual passenger. Designed to act as a flotation device, they have handles sewn to them to help you hug it to your chest. If you flip it around and grasp the handles, the pad now makes a very serviceable shield — especially against edged weapons.

I have heard some folks recommend detaching seat belts for use as flexible weapons, but until you actually try it (I have), you don’t realize how tedious and time consuming it is. An extension belt — if you get one — is much more practical, but still leave you stuck with a flexible weapon in a confined area full of other people. That’s not an ideal situation and a major reason I prefer to carry my weapons with me rather than scrounging them on the plane.

Some people look at a ball cap hanging from a metal carabineer on a backpack and think it’s a practical way to carry a hat. I think of it as politically correct brass knuckles. Paying $6.00 for a midget bottle of red wine seems like a crime, until you realize that included in the price is a sturdy club. And for the ladies who consider overachieving platform shoes a fashion statement, don’t forget they also work well when swung like a hammer in selfdefense. With a little forethought and planning, you can easily tote along some innocuous items that have serious weapon potential.

My absolute favorite items are “weapons grade” souvenirs — trinkets and keepsakes that seem harmless, yet offer serious weapon

attributes. Two of my prized examples of this genre are a miniature Seattle Space Needle made of solid brass and a cultured-marble miniature Washington Monument. The former is far nastier than any commercial Kubotan I’ve ever seen and the latter is, for all intents and purposes, a push dagger. Nevertheless, both were perfectly “legal” souvenirs purchased in the secure areas of airports. Similar items of this genre include large souvenir shot glasses, souvenir ice scrapers, and those giant kids’ pencils that are stout enough to kill vampires.

If you happen to find a favorite weapons-grade souvenir, get a bag and a receipt to go with it and carry them all together. That way if it is ever questioned, you can at least document the fact you bought it at an airport, therefore it must be safe.

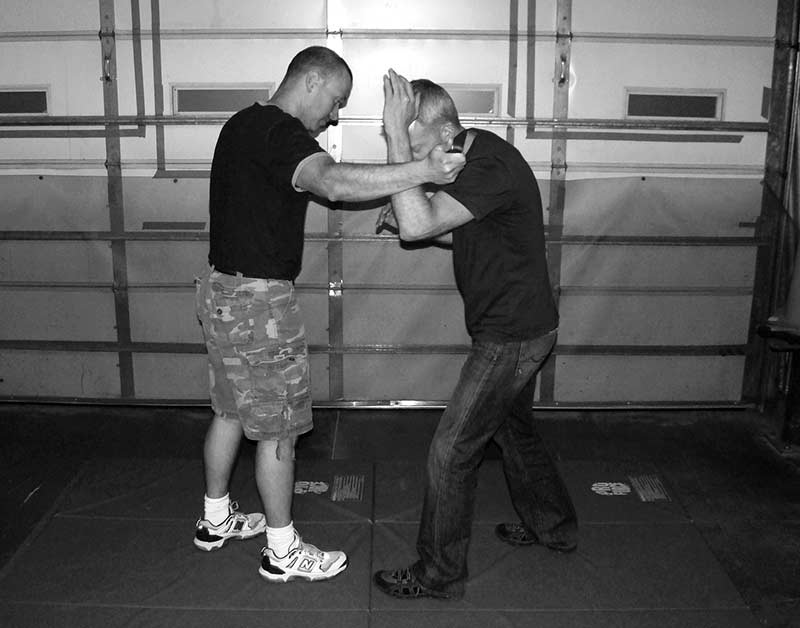

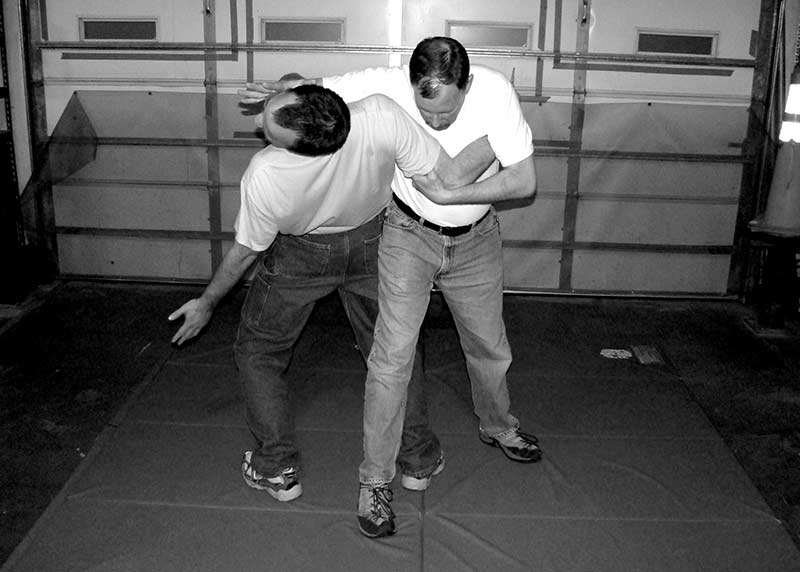

Close Quarters Pinball Close Up:

To learn to adapt your skills to confined-area applications, you must practice them in realistic environments. Here a narrow area between a wall and a railing becomes an ideal simulation environment. After the defender blocks the initial cut and executes an elbow strike to the limb, he “pinballs” the attacker’s head into the wall, learning to make the best use of his surroundings.

Rule #4: Be Aware Of Your Environment

Several years ago, I was selected as one of 12 self-defense subject matter experts to participate in the development of the TSA’s aircrew self-defense program. The other members of the team included some highly respected trainers with great insights into realistic selfdefense. However, after we all went into the aircraft training fuselage to demonstrate the details of our personal “takes” on the topic, it was very clear some of them — as talented as they were — had not adapted their tactics to the environment. Specifically, one of them — an accomplished Brazilian Jujitsu player — insisted the most critical skill a flight attendant could learn was how to use the “guard” position to keep from being beaten by a terrorist.

Conveniently, he and his demonstrator chose the galley area of the cabin to demonstrate their technique. I, along with two good friends who also happened to be in charge of close-combat training for the U.S. Air Marshals, decided to “follow along” from our position in the narrow aisle of the coach cabin. We quickly established the fact the prefered technique would only work in that one area of the plane and therefore had little overall value. Suggesting the demonstrator wear a skirt while demonstrating the guard (after all, that’s quite possibly what a flight attendant would be wearing) added insult to injury, but ultimately focused all members of the group on the realities of fighting in that environment.

To put it bluntly, most martial arts and self-defense techniques don’t work very well in extremely confined spaces. Techniques requiring lots of footwork and movement will not work. Similarly, restraint tactics like arm bars don’t work well when there is no room to apply them and when the attacker has so many things to grab to counter the technique.

When teaching seminars and private classes with my students, I am often asked why I don’t teach more footwork. Rather than preaching to the students, I usually move them to a tight hallway, closet, or other confined area and have them do their techniques. They quickly realize having the ability to perform a technique in place — or while moving forward to take your attacker’s space — is the most difficult and critical skill. It’s also the only skill that works in tight quarters. Adapting techniques to more open areas is far easier than adjusting techniques based on footwork to function without it.

In general, you should focus your tactics to emphasize powerful, close range tools and compact, linear lines. Elbows, knees, stomps, and palmheel strikes should take priority, and should be accompanied by eye gouges, head twists, and other vicious tactics that are ruthless and powerful enough to grind an attacker to the deck right on the spot.

Although the confined quarters of an aircraft cabin present more disadvantages than advantages, there is a tactical “bright side.” Once again, think of capitalizing upon the weapons that already exist in an aircraft cabin. Then think of the last time you stood up and banged your head on the overhead luggage compartment. Now, imagine grabbing a terrorist by the head, perhaps motivating him with a thumb in each eye, and bouncing his head forcibly off the overhead compartment, chair backs, arm rests, and every other pointy or angular surface you can find. I call this “pinballing,” and if you think of a ball bouncing rapidly and repeatedly off the bumpers of a pinball game, you’ll get the true visual of what the tactic represents. Any technique enabling you to control and direct your attacker’s head or body is a great platform for this tactic.

Rule #5: Practice Intervention Tactics

One very plausible scenario on an aircraft is that of a terrorist attacking a flight attendant or other passenger. In this situation, we civilized folks have the unfortunate instinctive reaction to grab the attacker to try to control him and peel him off the victim. In reality, our goal should be to take the cheapest shot possible to disable him while he’s not looking. As logical as this may sound, it’s not what people will normally due under stress.

My favorite tactic for blind-siding a violent attacker is to start with a hard stomping kick to the back of the knee to break his balance and drive him to his knees. This is immediately followed by a double cupped-hand blow in which you slap both of his ears — hard — with your cupped palms. Ideally, this will pop his eardrums, but at the very least, it will hurt like hell and have a significant effect on his balance. Without breaking contact after your double slap, twist his head forcefully to the side and plant him face down on the floor. Continue to follow up with hits as necessary and enlist the aid of other passengers to stand on his arms and ankles to hold him down.

Rule #6: Use Team Tactics

Remember, there is strength in numbers. If you travel with colleagues, family, or friends, talk with them about the issue of selfdefense on a plane and discuss basic plans in advance. You don’t need to be alarmist about it, but like any other emergency, thinking about it before something happens means you’re ahead of the curve.

Similarly, taking the time to “break the ice” with the passengers around you not only tunes up your social skills, but it makes it a lot more likely that they’ll jump in and help if you are forced to take action against a terrorist. Although “profiling” to identify potential bad guys has a bad name, when you’re sizing up potential allies, remember the big guy built like a football player might be a better asset than the 98-pound accountant. And, as long as you do it discreetly, continue to profile everyone else to identify potential threats as well.

The simplest form of team tactics is to have your traveling companion watch your back while you take action to deal with the threat. Since terrorists often act in pairs or groups, even if you are successful in dealing with one, while you are focused on him you leave yourself vulnerable. A rear guard therefore becomes a tremendous asset.

Another very basic, but incredibly useful skill that takes advantage of “helpers” is the ability to issue clear verbal commands. Let’s say you take on a terrorist and manage to get him down to the floor. Rather than ambiguous requests like, “Help me,” plan on specific commands like “You in the green shirt, stand on his arm and don’t let him move!” Keep it simple, clear, and effective.

Finally, if you have a colleague or travel companion who shares your commitment to personal protection, work out some simple but effective “double-team” strategies that will stack the odds in your favor if an incident occurs. A simple example against a terrorist armed with an edged weapon might be for one of you to grab your seat cushion, using it as a shield and a tool to smother the terrorist’s weapon arm. While you hold it immobile, your buddy uses low-line kicks to break knees and ankles to take the attacker down.

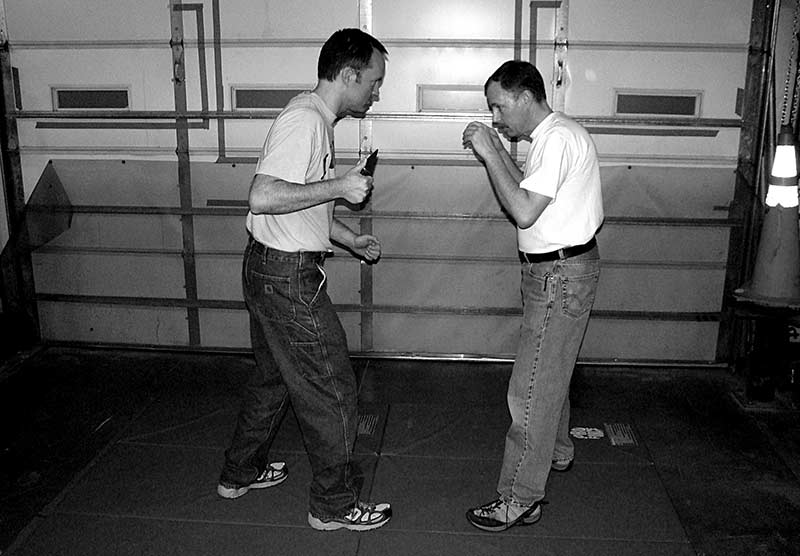

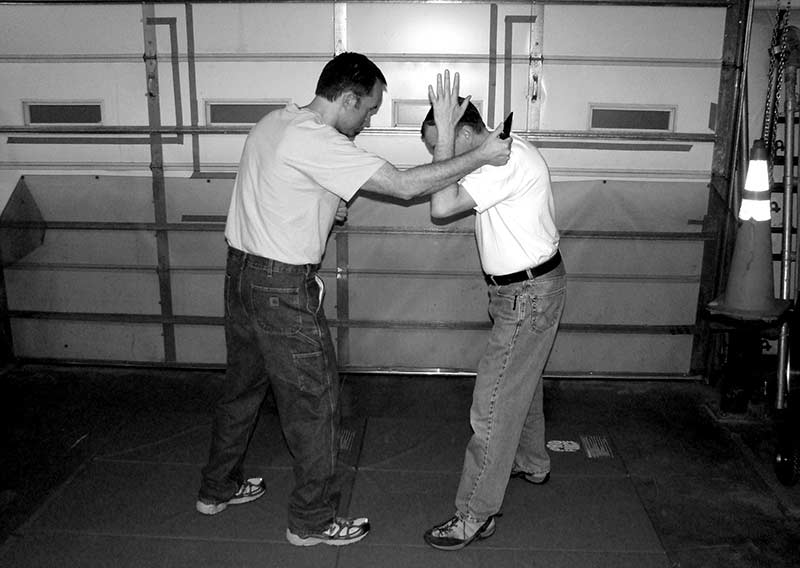

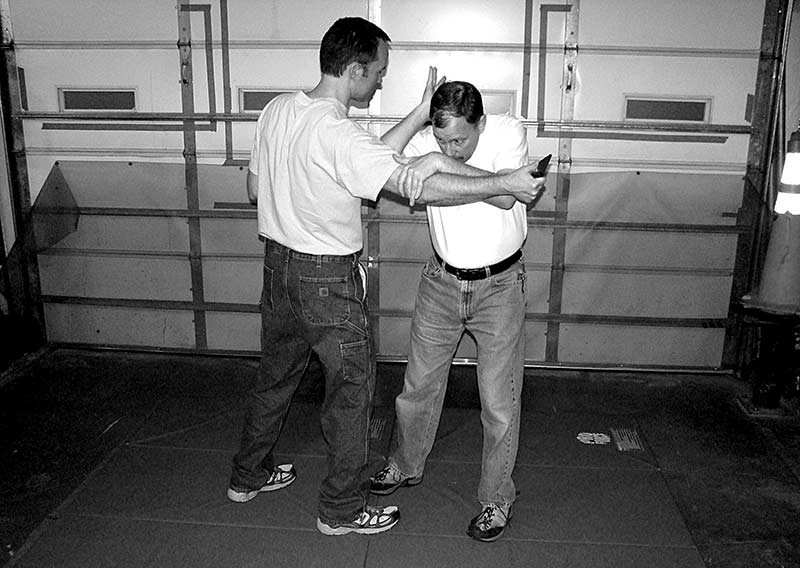

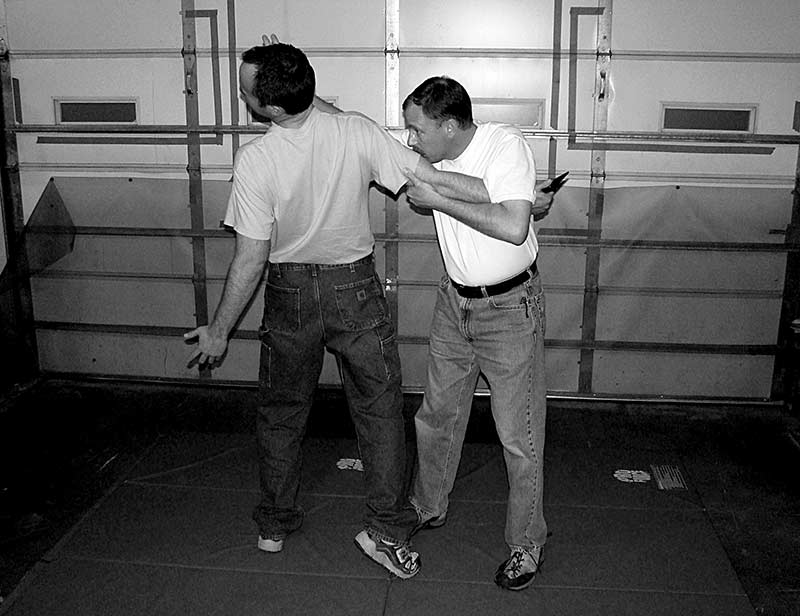

Knife Defense with Room

This sequence shows a practical defense against a knife attack. The defender blocks the initial slash, strikes the knife arm with a right elbow, and then executes a “Linda Blair” head-twist takedown. The finish drops both knees and full body weight on the attacker while maintaining control of the limb.

Rule #7: Think Your Plans Through To The End

One of the other amazing — and disturbing — aspects of my experience working with the TSA program was their inability to plan through to the conclusion of an incident. If someone gets up and threatens the safety of an aircraft full of people, they need to be stopped and kept that way through effective restraints. The TSA answer to the latter was duct tape or medical tape (carried on board, but not readily accessible) or an improvised restraint using extension seat belts or passengers (clothing) belts. Unfortunately, the techniques of actually doing this were never really addressed.

To keep a better solution simple and readily available, consider this: First, subdue the bad guy with hard, effective strikes. Then, prone him out, pinning the side of his head to the floor and having other passengers stand on every one of his limbs to pin the rest of him to the floor. Have someone remove their shoelaces. With help (and additional strikes as necessary), move the terrorists arms until the backs of the hands are together. That way you can use the shoelace to tie his fingers together right near the knuckles. Pull off his shoes and socks and use another shoelace to do the same thing to his big toes. This is much more effective than trying to bind his wrists or ankles, though you should feel free to do that too.

Finally, move him away from other passengers — especially the ones with short memories and compassion for the wrong people.

Rule #8: Get Off The Couch And Train

The fact that you’ve read this far into this article is a very good thing. But don’t be content with that. Find training partners with the same beliefs, goals, and convictions you have and actively practice this stuff. If you don’t have a combatives skill set, seek out proper training and get one. Then practice it diligently so you can really use it if you need it.

Rule #9: Make Your Training Realistic

Let’s say you already train and have a solid set of combative skills. That’s excellent. However, if you’ve only practiced these skills on a wide open dojo floor with nice cushy mats, you’re still not prepared. Grab your training partner(s) and either find or build a training environment replicating the confined quarters of an aircraft cabin. Then, practice the techniques you know and see if they are really appropriate and functional in that scenario. If they’re not, adapt them until they are or seem out other techniques that do work in close quarters.

Real, effective personal protection is all about developing skills appropriate to the threat and the environment in which you will be operating. If you want to be safe when traveling on an aircraft — and have the potential to keep many others safe as well — consider the information in this article and use it to structure your training accordingly. Stay safe.

Subscribe To American Handgunner

Get More Personal Defense Tips!

Sign up for the Personal Defense newsletter here: