1917 Classics

Too Much .45 ACP Fun!

When the United States declared war on Germany in April of 1917, as usual the politicians caught the American military woefully unprepared. France, Germany and Britain had been battling with airplanes and tanks for several years, yet the United States had none of those weapons. The shortages extended all the way down to rifles and even sidearms. America’s gunmakers were called upon the fill the breech.

It can never be said handguns are war winning weapons. At best they are personal defense items, mostly meant for officers and members of crew-served weapons teams. Still, it would have been inexcusable to send officers out into no-man’s land armed with nothing, so the US Army had to find alternates for the 1911s that didn’t exist in enough numbers.

In 1917 both the Colt and Smith & Wesson factories had large bore revolvers in their line-up. Colt’s was the New Service, which was being offered in bore sizes ranging from .38 to .45. In fact as recently as 1909 the Colt New Service had been adopted as official handgun of the US Army in .45 Colt caliber.

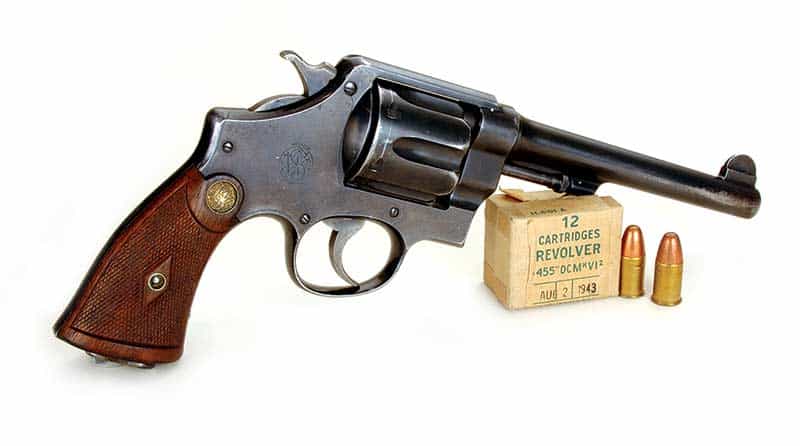

Smith & Wesson’s big revolver was based on their relatively new N-frame, which in 1917 was in its second model configuration. The factory called it the Hand Ejector, 2nd Model. Essentially that meant it did not have the large barrel under lug which encased the ejector rod. This revolver was mostly made in .44 caliber but the Brits had already bought over 70,000 of them chambered for their puny .455 Webley cartridge.

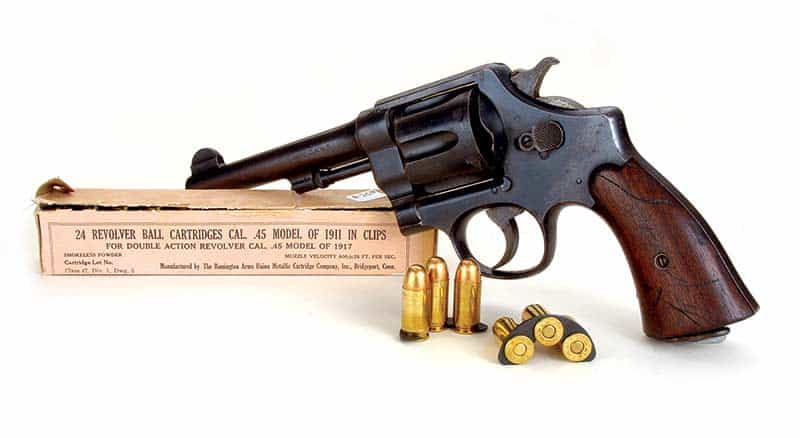

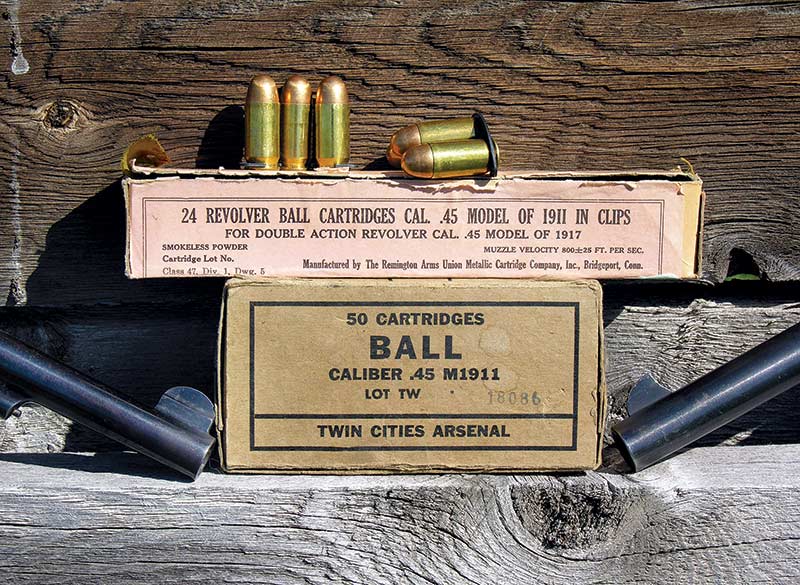

Some bright engineer at Smith & Wesson must have seen the coming problem with handgun shortages and recognized the fact the US Army would want to buy revolvers chambered for its rimless .45 ACP cartridge. So he developed a little spring steel clip into which three .45 ACP rounds could be snapped. Two of these loaded clips could be dropped into the chambers of sixguns; giving a surface for the revolvers’ star extractors to push against. Luckily the dimensions of Smith & Wesson N-frame and Colt New Service cylinders were close enough the little spring steel clips fit both perfectly. Hence was invented what has come to be known as “halfmoon” clips and — US Army Models 1917 revolvers.

Ramping Up

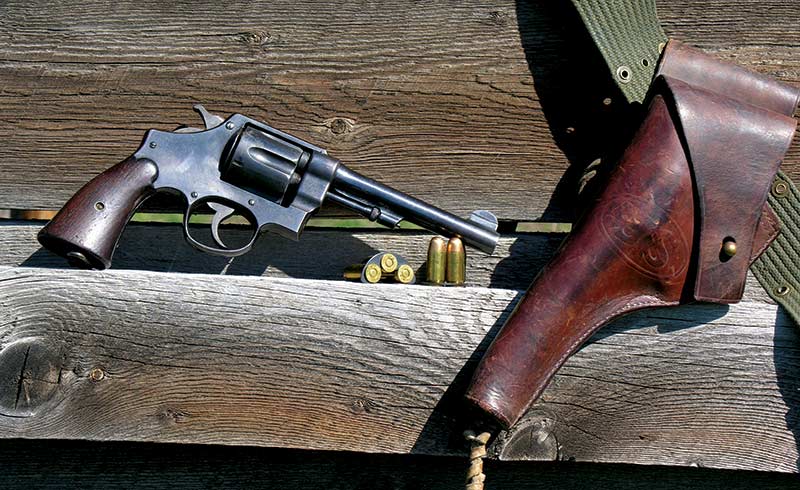

Showing what manufacturing feats American firearms manufacturers USED to be capable of, the Colt and S&W factories each turned out over 150,000 of the Model 1917s in only a two year period. According to Bruce Canfield’s book, US Infantry Weapons of World War II, the government bought approximately 153,000 of the S&W version, and approximately 150,000 of the Colt one. Both company’s Model 1917s were of a type. They had 51⁄2″ barrels, lanyard rings on the butts, and of course they were standard functioning double action revolvers. Sights were blade fronts with simple grooves down the frame’s topstrap for a rear sight. Grips were plain, uncheckered walnut with no medallions. Finish on both were full blue, but it’s interesting to note Colt did not polish their Model 1917s, while Smith & Wesson went ahead with their standard commercial finish.

Other than their maker’s addresses atop the barrels, their other identifying stampings were “US Army Model 1917” on the bottom of the butts, and “United States Property” on the bottom side of their barrels. Here’s a little tidbit though. Most American military firearms (and other country’s for all that I know) are not caliber stamped. However these Model 1917s were; respectively having the marking “S&W D.A. 45” and “Colt D.A. 45.” on the barrel’s left side.

Seeing Battle

Some evidence the Model 1917 revolvers did see action is their attrition rate. After World War I when they were put into storage, only 91,500 S&Ws and 96,530 Colts were still in government hands. Again those figures are from Canfield’s book. Still, the Model 1917 revolver story did not end there. Evidently both manufacturers thought the idea of a revolver firing a popular autoloader rimless cartridge was a good one because both kept their .45 ACP revolvers in their catalogs after World War I. Smith & Wesson even kept the Model 1917 moniker, while Colt simply referred to theirs as the New Service. Colt made that particular handgun until 1944, and Smith & Wesson kept it in their line until 1949, with a break in production during World War II.

And speaking of World War II, as was the case in April 1917, again in December 1941 when the United States entered World War II, there were severe firearms shortages. So the Model 1917s were pulled from storage and reissued. They were considered a sort of “secondary” sidearm, with many going to prison camp guards here in the continental United States, but many did see action. There are photos of Model 1917 revolvers being used by US Army troops both in the European Theater of Operations and in the Pacific campaigns. Although these Model 1917s were marked “US Army” some also made it into Marines hands during the island fighting.

Still Going

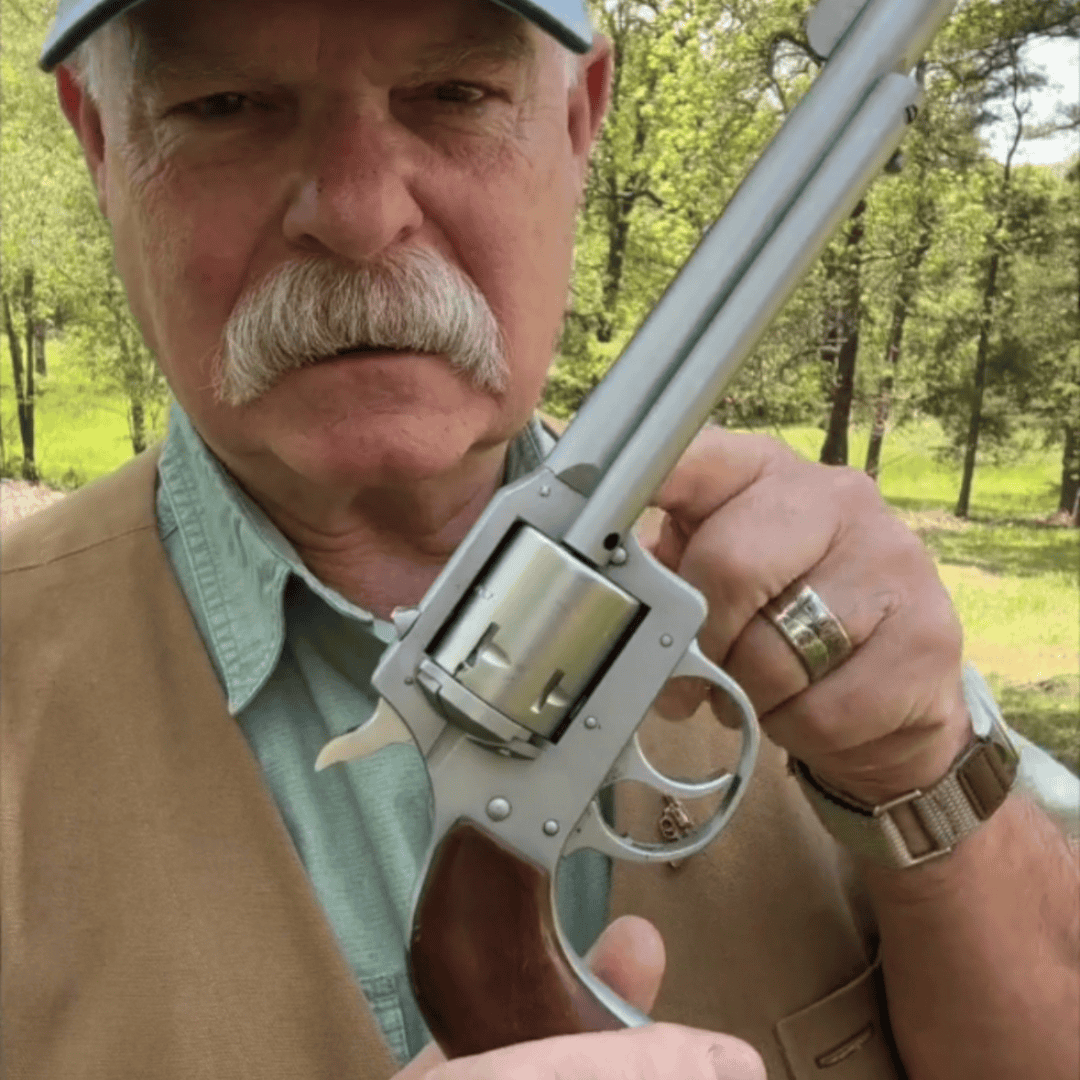

And still the Model 1917 story has not ended. Back in January 2007 at the SHOT Show in Orlando (incidentally 90 years after the 1917’s advent), I wandered into the Smith & Wesson booth to visit. There I was surprised to see Smith & Wesson had new 1917s. In fact three versions were on display; a full blued one, a fully nickel-plated one, and a third with color case hardened frame. Personally, that last one left me cold; whoever heard of double action Smith & Wesson revolvers with color case hardened frames? But, I’m sure they will be attractive to some. The nickelplated one left me indifferent, but the full blued version caught my fancy. After all, that’s what S&W Model 1917s are supposed to be!

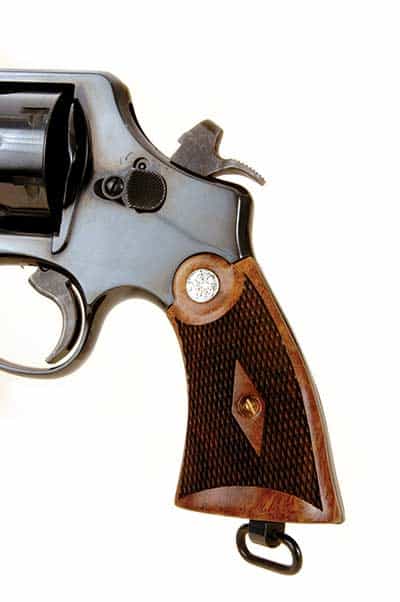

The new Model 1917s are not exactly dead ringers for their vintage ones. Their hammer spurs are wider at .400″ to the originals’ .26″. Front

sights on original S&W Model 1917s were forged integral with the barrel, but the new ones have pinned-in front sights. Both are shaped alike — the old half moon style that was almost a Smith & Wesson symbol. However, old S&W Model 1917 front sights were only .073″ wide and the new ones are a full .125″. Of course the thing that will cause the most heartburn among readers is the key-lock on the new Model 1917s, but with lawyers running the world that’s all we can expect. Smith & Wesson didn’t duplicate the smooth walnut military grips with these new Model 1917s, but instead fitted them with checkered Magna-style ones as were standard on their commercial issue 1917s toward the end of their production run. And the last major exterior difference is that the new Smith & Wesson Model 1917s don’t have a firing pin mounted on the hammer.

A Surprise

Something that did surprise me was the fourth screw located at the top of the sideplate. Smith & Wesson had discontinued that way back about 1957, so it was pleasing to see it again. And lastly the new Smith & Wesson Model 1917s do indeed have the lanyard ring on the butt. This revolver was also put together nicely. It has a deep blue finish with a nice polishing job, the grips fit near perfectly, and the barrel cylinder gap is a tiny .003″. Trigger pull is a mite heavy at 51⁄2 pounds but doesn’t have a lot of creep.

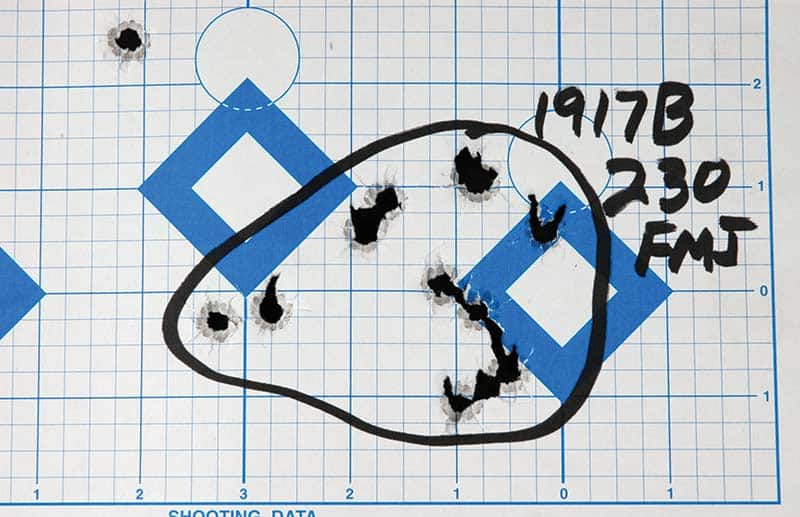

I’ve had considerable shooting experience with the original Model 1917s and a bit with the new one too. None of them — in my experience — can be considered tack-drivers, it seems to simply be the nature of the beasts. With 230 grain FMJ ammo they can be expected to group 10 or 12 shots in about 2″ to 3″ from sandbags or machine rest. Careful handloading can give better results, and in one project a few years back with the Colt 1917 I was able to get sub-2″ 10 shot groups with cast bullets loaded in .45 Auto- Rim cases. So I guess they can often be made to shoot, you just might have to try a bit experimenting with loads.

And that brings us to a small aside. Probably no revolvers can use such a wide variety of speed loaders as those chambered for the rimless .45 ACP. You can use the old three round halfmoon clips or newer six round “fullmoon” clips. And then there are the .45 Auto-Rim cases which work just as regular revolver cases. They can be put in regular speed loaders or loaded individually. Those .45 Auto-Rim cases fired appeared about 1921; introduced by the Peters Cartridge Company which later became part of Remington. And it is perhaps indicative of the continuing popularity of .45 ACP revolvers that both Black Hills Ammunition and Cor-Bon currently have .45 Auto-Rim factory loads once again.

Model 1917 revolvers of any vintage by either manufacturer are perhaps not the most practical of handguns today. But neither are Colt SAAs, Smith & Wesson Schofields, or Lugers for that matter. They are historical, which also makes them interesting to many of us. Originals are becoming collector’s items, so it’s refreshing a company as large as Smith & Wesson has seen fit to reintroduce a revolver from nearly 100 years in their past. Hopefully, they will continue the trend.

Subscribe To American Handgunner

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: