Coming Around on the Traditional Double Action

Right For Me; Right For You?

The gun shows here in Los Angeles are pretty terrible these days — I remember better times. Around the early 2000s, I was on the hunt for a few specific and rare pieces, and it seemed like just about every table had a “third gen” Smith and Wesson autoloader. Guns like the 5906 and 4006 were once mainstays of the LAPD, but as it became an increasingly striker-fired world, you’d see them more frequently up for sale with “USED” tags and asking prices of about $450.

As that old hair metal song by Cinderella goes: “You don’t know what you got—’til it’s gone.” Today, all of those ex-LAPD guns, along with any “beater grade” Beretta 92, SIG P226, or HK USPs are rare encounters in the consignment cases. Movies and TV shows like Training Day, Die Hard, Collateral and The Shield probably boosted the “ooh!” factor of a lot of these models, but I think the word got out: Far from archaic tech, the DA/SA autos are great guns.

I’ve certainly come around on them, and I think you might, too.

A Little History

Our story begins with the Walther P38, a revolutionary design for its era. Easier and cheaper to build than the iconic Luger P08, the P38 was, at the same time, more reliable and better suited to battlefield conditions. It incorporated an ingenious “falling block” locking system that continues to live on in the Beretta 92 models and its derivatives. And, most significantly to our topic here, it popularized what is now known as the DA/SA autoloading pistol — sometimes called a “traditional double action” auto, or TDA for short.

Unlike the single action auto, such as John Browning’s ubiquitous M1911, the TDA gun could be decocked after it was loaded to allow the trigger to work like a double action revolver: Through a long pull of the trigger, the hammer would be cocked and released to fire the first round. After that, the pistol would operate in the single action mode, with a lighter, shorter trigger pull to drop the already-cocked hammer for all subsequent shots.

Opinions of this system were — and remain — mixed. Regardless of whatever other safety features may be simultaneously engaged, a cocked pistol seems to invite apprehension from bystanders (and many gun owners) as something that could more easily “go off.” When carried as the designs are intended, the TDA auto avoids this perceptual issue while also ensuring the first shot isn’t going to break without deliberate, sustained motion of the trigger. And at the same time, the gun can be rapidly brought into action without having to disengage any manual safety.

The Gripes

Imagine yourself pushing a wheelbarrow loaded with bricks up a steep hill, and you’ve got a sense of what it’s like to work the worst triggers on a DA/SA platform. True, a long and heavy pull makes it harder to unintentionally discharge a round, but it also makes it harder to intentionally place shots where the user wants them.

I remember about 15 years back, a few of the IDPA guys on my shooting forum were running Beretta 92s and SIG P-series guns. They were asked how they managed that long DA pull. The advice seemed to be to mash the first round out of the gun to get it over with, then rely on the SA mode to produce hits.

Unsurprisingly, the “common-sense” wisdom from guys like these was to steer new shooters away from DA/SA platforms entirely. A familiar refrain: “Why spend time mastering two trigger pulls when you can just master one?” Following that line of thinking, novice shooters were directed toward striker-fired platforms, which were seen as simpler and more shootable.

Around the same time, law enforcement and military units seemed to be moving away from the TDA pistol in droves. As noted, I saw them first disappear from the holsters of LAPD officers. By the time the military switched from the Beretta 92 to the SIG P320 platform, the market seemed to have spoken: Just about nobody wanted to deal with that stiff, long DA pull if they didn’t have to.

Rethinking

I’ll admit I began to add a few DA/SA guns to my collection simply because of the initial challenge. I wanted to learn a new skill set, and so I forced myself to run any of my traditional double actions as their designs intended: with the first round out of the pipe shot DA.

Yes, this was harder. But it was hard and fun, much in the same way that car junkies will learn to operate a manual transmission, a vastly more complex process than what an automatic transmission requires from the driver. They certainly don’t have to as a matter of necessity, but for most “slushbox” haters, the process of shifting gears connects them more closely to the machine and to motorsports writ large. Often, it teaches them to be better and more conscientious drivers.

In getting to know the DA/SA gun, I arrived at a number of benefits. First, it helped me conquer my flinch. Jerking the trigger almost always resulted in a miss. Pulling slowly and deliberately, however, was an act of fine motor control. An accurate shot in DA only came through repeated stress inoculation: You are tasked with executing a kinetic operation with consistency and fluidity, knowing full well it will result in an explosion. Easier said than done! I feel it is this aspect in particular that causes most shooters to turn away from the platform.

Second, it taught me the trade-off between speed and accuracy. It is easier to make a center-punched hit in the DA mode of these autoloaders when you take your time — time you may not have in a critical situation. Speeding things up involves learning how to try to compress that fluid pull rather than jerking on the trigger to rip a round out of the pipe. As a result, the TDA auto allowed me to shift from a binary hit/miss assessment of my shooting to one that was more dynamic: How quickly could I make a hit on a target at a specific distance? Was there room to push myself a little faster, even if I knew my groups would open up a bit?

By the same token, I began to appreciate the degree of mechanical safety present in these designs. At least to me, and if we’re talking about the systems of a handgun’s design that prevent the unintended discharge of a round, there’s a difference between “shouldn’t” and “can’t.” I understand, intellectually, how the various safety systems of striker-fired firearms work. I don’t know how much I would absolutely trust some of these guns to keep the striker cocked if they were hurled down a flight of stairs.

On the other hand, it’s hard for me to imagine how an accidental discharge would happen on my Beretta 92 if knocked or dropped: Its firing pin is prevented from forward travel unless the trigger is fully depressed, and at rest, its hammer lacks the spring tension to bust primers.

The TDA Today

You don’t need to look hard to find examples of the TDA that are still being produced. I’ve mentioned the H&K USP, SIG’s “P22X” series of guns, and the Beretta 92, which have all remained in continuous production. To those, I’d add the HK P30L, several of the CZ-75 models, and IWI’s Jericho models. Clearly, these are successful products with several decades of avid buyers to vouch for their effectiveness.

The Beretta 92 deserves special mention because of a small renaissance these guns are experiencing as “semi-custom” platforms thanks to Wilson Combat and Langdon Tactical. I’d do a disservice to Bill Wilson and Ernest Langdon to try to parse all of their thoughts on the Beretta 92 in the space I have here, but I did want to signal out one small bit of wisdom from Mr. Langdon: I came across a recent video in which he too praised the TDA auto because of the deliberation required to fire the first round.

However, Langdon said the deliberation comes from the length of the trigger pull, not necessarily the weight of the pull. This is a biggie.

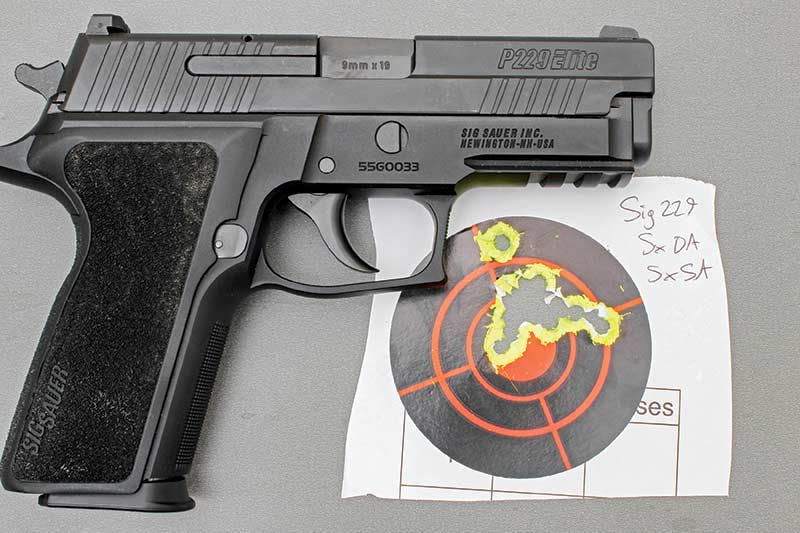

Over the last 20-some years, bright minds have expended quite a lot of effort to re-engineer the lockwork of many of these already excellent TDA models. As a result, the DA pull can go from a chore to a delight. The LTT Beretta 92 has an advertised DA weight of 6.3 to 7 lbs., and my own SIG P229, after coming back from the wizards at Grayguns, has a buttery DA pull of 7 lbs. on the dot. Where shootability is concerned, a great DA trigger makes a tremendous difference.

I suppose if you put my feet to the fire, I’d agree the DA/SA auto might not be the best choice for a total newcomer to shooting. However, to conclude these guns are obsolete is simply a bridge too far. On the contrary, I would say these platforms are superlative for teaching intermediate shooters how to reach the next level of performance, supposing they can work under a stern taskmaster. An expert will easily overcome the learning curve.

Along the way, such shooters might surprise themselves as the DA/SA handgun goes from an intriguing historical novelty to the platform they’d prefer to have at their side for the defense of life and limb. That’s exactly what happened to me and judging from my continued search for a clean and affordable S&W 4506, I think there are a lot of guys like me out there.