Handguns Of WWII, Part 9

Smith & Wesson Model 1917

Part 9 Of A 13-Part Series

Perhaps the British could claim at least a small amount of credit for the advent of Smith & Wesson’s Model 1917 .45 Auto revolver. Just into World War II they first contracted with the company to buy Hand Ejector, 1st Model revolvers famously known as “triplelocks” converted to fire their .455 Webley cartridge. Besides that third lock securing the cylinder crane to the main frame, those handguns also had a shroud covering the ejector rod on three sides.

The British said their experiences in the mud of trench warfare showed those two features to gather debris causing the cylinder to bind. Smith & Wesson listened and developed the Hand Ejector, 2nd Model in 1915 omitting those two problem areas. Between 1st and 2nd Models Smith & Wesson sold the British Government nearly 75,000 .455 Webley chambered revolvers.

Smith & Wesson, Hand Ejector, 2nd Models normally were chambered for .44 Special and they continued as such in the company’s catalogs until 1917, when Woodrow Wilson stuck America’s nose in European affairs, declaring war on Germany in April of that year. This put the U.S. Army in a mad scramble for weaponry.

Handguns are not war-winning weapons. In terms of offensive actions they were important with horse soldiers, precisely the purpose for which the U.S. Army’s then standard handgun had been primarily devised. That of course was the U.S. Model 1911 .45 ACP. However, in the World War I era, handguns were also (usually) the sole armament of officers and also many types of service troops whose duties took them near or into the front lines. Not nearly enough Model 1911s existed, nor could be quickly produced, to go around.

Gearing-Up

It was fortuitous America had two giants among handgun manufacturers in 1917. Those were Colt and Smith & Wesson and both already made large frame handguns. The only fly in that ointment was the .45 ACP had been devised to function in autoloaders, so its case had no rim. And of course the star type extractors used in double action revolvers needed a rim to have something to push against in order to eject rounds from the chambers.

Some smart soul at Smith & Wesson had already solved that problem with a fast and cheap solution. Today we call them “half-moon clips.” They are nothing more than stamped pieces of steel into which three rounds of .45 ACP snap, by means of the clips’ edges going into the cases’ extraction grooves. Bore the chambers for the .45 ACP, and arrange the headspace to account for the clips’ thickness, and you have a revolver capable of firing rimless cartridges.

The U.S. Government evidently loved the idea and so gave the go-ahead to both Colt and Smith & Wesson to produce what were designated U.S. Model 1917 revolvers. That designation in itself deserves a moments’ thought. To the best of my knowledge this was the only time the U.S. Government gave the same name to two completely different firearms, of which no two parts would interchange. That must have given military armorers some headaches. Also as one of my photos show, .45 ACP ammunition for 1917 revolvers was issued already attached to the “half-moon clips.” Knowing human inefficiency I would lay money that units armed solely with 1911 pistols received cases of 1917 pre-clipped ammo.

Barrel Lengths

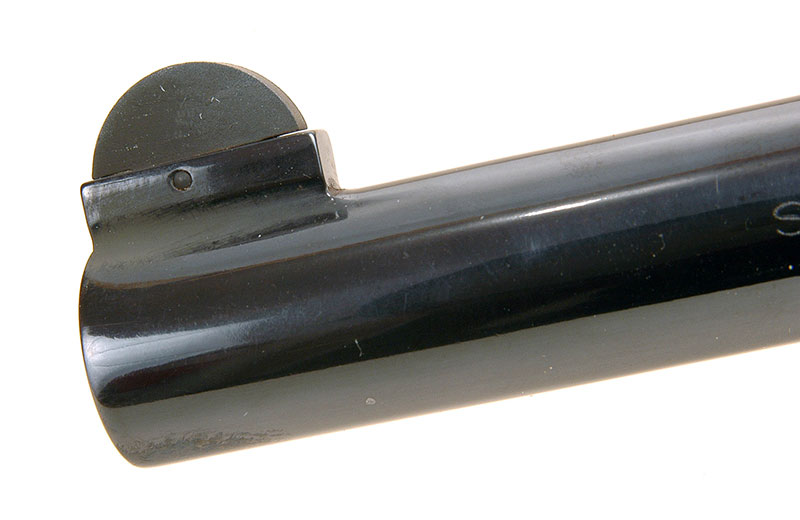

Until this point Smith & Wesson’s Hand Ejector, 2nd Model barrel lengths had been standardized at 4″, 5″, and 6 “. The British bought all their .455s with the latter length. The U.S. Government figured that was too long and instructed Smith & Wesson to make their new .45 revolvers with 5 ½” barrels. The company gave these military handguns the same exquisite bright blue finish as put on their commercial revolvers. Also differing from civilian Smith & Wesson revolvers, a lanyard ring was installed on the butt. Markings were “U.S. Army Model 1917” also on the butt, and “United States Property” under the barrel. Over 150,000 were made by Smith & Wesson between 1917 and 1919.

That was the beginning and would have been the end of the .45 ACP revolver story, as regards the American military, if not for World War II. When we entered that fracas, again there were not enough 1911 pistols to go around and the need for them was even greater, as members of crew-served weapons, armored vehicles, and even flight crews were issued handguns. What 1917 revolvers survived World War I and the interwar years were stored in various arsenals. They were pulled out, refurbished, given a Parkerized finish and then used again. There are many photos of World War II combat troops holding U.S. Model 1917s, and interestingly most I have seen were Smith & Wessons.

Click here to links to all the 13-part on-line series of Handguns Of World War 2 articles.