Military Surplus For Self-Defense?

Good Reasons To Just Say No

Let’s suppose you’re a budget-minded consumer looking for a handgun you might need to defend your life with. A trip to the local gun store could prove to be discouraging. While the market isn’t lacking in terms of reliable and accurate service-grade semi-autos, it’s often hard to source a quality handgun in this category for less than $500.

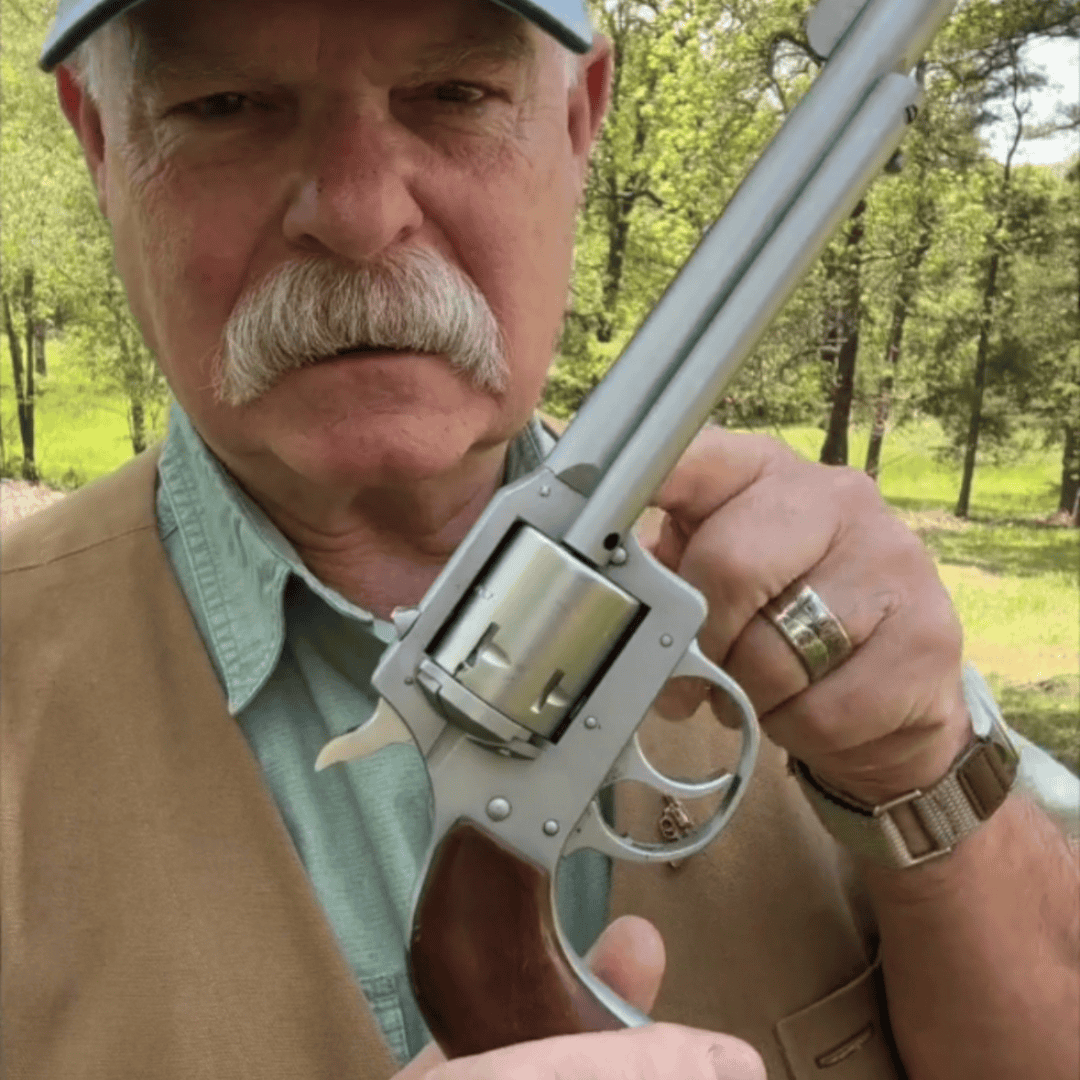

From this vantage point, we can see how military surplus pistols become tempting self-defense options. I mean, after all, shouldn’t these affordable guns do just as well, if not better than today’s civilian offerings? These were designed for soldiers to use under the conditions of war, had to be at least easy enough for a grunt to operate and maintain, and had to have a level of power making them combat-effective, right? Right?

The truth is while a military surplus handgun can make for an incredibly neat piece of shootable history, there are a few very crucial things you need to keep in mind before conscripting one into the role of a self-defense arm or carry pistol. If it’s an avenue you’ve considered, let’s run through what you may be coming up against.

It’s No Longer 1950

It could be argued virtually every consumer good we have now is the product of decades of innovation and refinement. Most automobiles made today are safer and easier to drive than those rolling off assembly lines in the 1950’s. Alternately, compare a computer mouse made 20 years ago to one today. Those clunky gray mice of yore, with their single rectangular button, will seem downright primitive. Here’s where I’m going with this: as a product category, guns aren’t a whole lot different.

First, many military surplus handguns require a different “manual of arms,” which is a fancy way of saying there’s a difference in the way they operate. Today, consumers have been quite clear in their preference for thumb-accessible magazine releases. And, if a firearm must have a manual safety, we typically prefer it on the frame.

Be aware this is not the case with most of the European autos forming the bulk of today’s surplus. If pushed into a self-defense role, you must often learn the awkward process of disengaging slide safeties as part of the presentation — or be comfortable with not using them in the first place.

Reloads will often require engaging heel-mounted releases. This, in turn, requires additional effort to strip the magazine out of the gun since it will be pinned in the magwell through spring pressure. Then, a new magazine must be re-inserted into the gun in such a way the heel release is pushed backward, but not in such a way the motion would disturb the top round in the magazine. This is all relatively easy to do in the light of day, but how might you fare testing these motor skills in the dark and with a full dump of adrenaline?

Consider also most surplus guns are devoid of the accouterments found on modern designs purpose-built for self-defense. Rails? Forget about ’em. If you want a light, you’re going to need to hold it. Usable sights? Most military doctrine held handguns were a last-ditch defensive weapon most likely used in extreme close-quarters combat, so precision wasn’t a high priority. Night sights? Forget it, buddy: they haven’t even been invented yet.

Unreliable — Or Worse

Even if a shooter is fine with the operation of the gun, which could fall anywhere between “no frills” and “out-and-out cumbersome,” it’s important to note there are major issues of reliability to test and failure points to be aware of before chambering a round and going on your merry way.

A biggie: many of today’s surplus guns were simply not designed to feed hollow points, instantly rendering them sub-optimal when it comes to a dedicated self-defense role. In some cases, the use of anything other than the ball ammo for which they were originally designed will cause the gun to fail.

In the German P1’s, essentially an alloy-framed derivative of the famed Walther P38, use of +P ammo is strictly verboten. The higher pressures may cause the top cover to blow off and vomit essential gun parts forward of the shooter. Even substituting standard-velocity 124-gr. ammo in my P1 as opposed to 115-gr. loads caused my slide safety to eventually work its way downward through the course of a magazine.

Along these lines, it pays to remember all of the little fiddly bits inside surplus guns were made god knows how many years ago, and out of steel compounds often fragile and already service-worn. Quite a few firing pins are notoriously brittle and simply do not hold up to dry-firing. Leaf springs sometimes snap, causing instantaneous dead triggers. And speaking of breakages, the Sig Sauer P6 is another interesting case: it was designed with a hammer cutout so the part would snap when dropped. The idea was since the stress would likely be transmitted to the gun’s action, a broken hammer would probably identify guns with screwed-up internals. The moral — soldiers drop a lot of guns.

It’s also imperative to test the functioning of the gun’s controls before a live round is chambered. My CZ-52 shares a common (and unenviable) trait with many others — the decocker does not safely decock the gun. Instead, it acts as a second trigger. “Decock” the gun on a pencil placed against the breechface, and the firing pin will strike the eraser hard enough to send it clear out the end of the barrel. Sometimes, safeties in military surplus pistols aren’t. Trust them at your own peril.

Bear in mind each of these pistols arrives to you of questionable provenance. Unlike the soldiers who were the first to carry your gun, you don’t have the benefit of an armorer to fix your pistol when it goes down, nor do you have the backup of a nearby soldier and his rifle.

Maybe Not A Great Deal

I spoke to Willy Clark, gunsmith at American Gun Works in Glendale, Calif. about what he thought was necessary — at a bare minimum — to turn a surplus pistol into a suitable defensive weapon. He suggested a ramp and polish job in order to reliably feed most varieties of today’s hollow points. At AGW, the price for such a modification carries a price tag of $150. Money well spent, certainly, but the “value” of a surplus pistol as a carry or home defense gun is now beginning to erode. That goes doubly so if parts need to be replaced, if machining burrs need to be filed down, or if the customer wants a smoother action. A new spring set would be a good idea too.

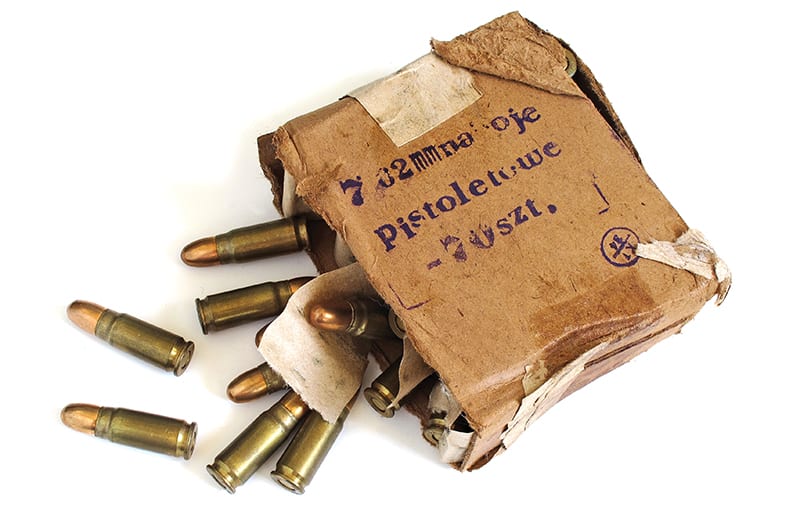

Willy also mentioned another good point about surplus ammo. Since they’re not making any more of it, it’s only going to become more expensive. Three years ago, I purchased a massive tin of more than a thousand 7.62 Tokarev rounds for just over $100. Today, the best surplus deal I can find for the same ammo is 800 rounds for $250. Not that you’d actually want to use those rounds for any kind of personal defense, of course.

The Point

I should be clear this list is by no means complete. After all, there are a variety of additional issues which might come up with a military surplus pistol, including the self-defense implications of cosmoline-gooped internals, extraordinarily heavy trigger pulls, ammo availability of oddball rounds and the corrosive primers of most surplus ammo.

We’ve all heard the anecdote about soldiers grumbling when their 1911’s were replaced by Beretta 92’s. This yarn is the exception, not the rule. Most of the time, the pistols replacing a country’s aging supply of Cold War-era handguns were considered to be out-and-out upgrades, and few soldiers looked back with fond memories on what was dumped onto the market. And even the 1911, venerated as it is, should be checked for proper functioning if a buyer wishes to enlist a surplus model as a self-defense arm.

I’m sure some readers have a Bulgarian Makarov gobbling up newly-manufactured JHP’s with ease and goes bang every time. Fantastic, I say, keep on keeping on. My point is not every surplus arm is reliable or optimal for personal defense.

Surplus guns are fun. Buy ’em, shoot ’em and enjoy ’em. But be smart and do some research if you’re pondering one for defense. Above all else, ask yourself if it might simply be better to spend a little more cash up front instead of trying to turn a sow’s ear into a silk purse. Your life is certainly worth it!

Remember the adage about riding a motorcycle? A ten-dollar head deserves a ten-dollar helmet.