Minute But Mighty: Made Fortunes; Armed Generations

Pocket-Sized .32 Revolvers

From the 1880s through World War II, inexpensive, nickel-plated, double-action pocket revolvers chambered in .32 rimfire or .32 S&W centerfire became extremely popular self-defense handguns in America. Largely forgotten companies like Hopkins & Allen, once America’s third largest manufacturer of firearms after Colt and Winchester, Harrington & Richardson, Iver Johnson and Forehand & Wadsworth churned out little nickel-plated, solid-frame and break-open revolvers of decent quality in prodigious numbers. They went into the pockets and nightstand drawers of safety-conscious people of modest means. In addition to the big four, there were smaller, less well-known manufacturers. Some made revolvers as good as the big four, but most of them were of lesser quality and some were even craptacular.

This tiny Iver Johnson five-shot American Bulldog was that company’s

answer to the H&R Young American. These pistols were so small they

could fit in the palm of the hand. The Forehand & Wadsworth company

of Worchester, MA, offered its improved five-shot revolver in .32 rimfire

and .32 S&W centerfire in 1880. The company had developed many

patents and made guns of good quality.

Budget Protection

For the most part, these little guns were less mechanically refined than the somewhat larger pocket double-action revolvers produced by Colt and S&W. I’ve never seen one with a swing-out cylinder, and bolt-stop cuts on a cylinder are a rarity. Likewise, they were generally not as durable, reliable or finely finished. The most expensive of these value-priced pocket wheelguns sold for approximately a third to half the price of a Colt or S&W, and the lowest-priced guns could be bought for an eighth of the cost! Lesser-quality double-action revolvers were cheaper still, and several firms specialized in making them.

However, there were even cheaper pistols. If you had less than a dollar to spend in 1899, you were limited to the bottom of the self-defense barrel, which held the worst of the .22 rimfire, single-action, solid-frame and spur-trigger revolvers. Consumer expectation was that they would work at least once. Somewhere along the line, I suspect long after their heyday, these guns got the nickname “suicide specials.” The inexpensive pocket double actions, produced with increasing efficiency that permitted low prices, eventually killed demand for obsolescent single-action pocket revolvers.

Both Hopkins & Allen and Forehand & Wadsworth also made lower-quality lines for various retailers, sometimes bearing absurdly intimidating trade names like Tramp’s Terror. Unlike the other big four little-revolver manufacturers, Hopkins & Allen doesn’t seem to have been embarrassed by marketing guns of low quality with its trademark. They made guns of all kinds, some of which, like Merwin & Hulbert revolvers, were of superb quality, so I suppose they assumed their reputation wouldn’t be hurt if they dove deep to scoop up the profits lying at the bottom of the market.

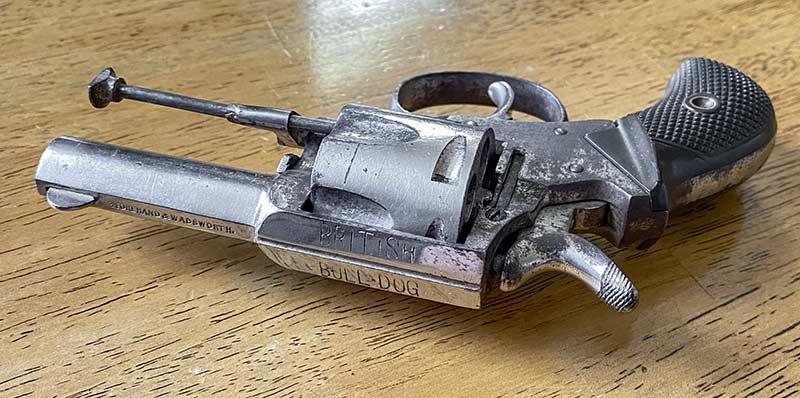

Inexpensive, compact, Bulldog-type revolvers in .32, .38 and .44 caliber

were imported from England and became popular in America. Unbound by

U.S. patents, these pistols were quite advanced for their time with folding

ejectors and loading gates, the latter broken off of this .38-caliber example

imported by Forehand & Wadsworth around 1880.

Popular But Not Particularly Powerful

So many of these little pocket revolvers were made. H&R made 1.5 million Double Action Americans alone and they are still commonly found in antique shops, estate sales and gun shows. Very nice, shootable examples often cost less than $150. Any of them made before the turn of the century were meant for black powder cartridges, and I’d never advise shooting these with any smokeless powder load. The typical .32 S&W black powder cartridge used an 88-grain soft lead bullet over 9 grains of black powder. I reproduced this load and chronographed it at an average of 522 fps from the 2.4″ barrel H&R Safety Hammer revolver shown in this story. That velocity is comparable to what I’ve found in vintage ammunition, suggesting it delivered about 53 ft-lbs of energy at a range of 15′. If you exclude the .22 rimfires, this makes it about the least powerful metallic cartridge self-defense caliber commonly used in America. For comparison purposes, and using energy calculated when fired from a 2″ barrel for convenience: .25 ACP has about 68 ft-lbs, .32 ACP has 96 ft-lbs, .380 ACP has 135 ft-lbs and 9mm Luger has 229 ft-lbs.

Curiously, .32 S&W has a fairly loud report when loaded with black powder. Perhaps this added something in its favor as a self-defense cartridge beyond what its unintimidating ballistics suggest.

The solid-frame Harrington & Richardson’s American line of double

actions was extremely popular from 1880 until production ceased in 1941.

Both of these models are the patented “SAFETY HAMMER” type designed

for snag-free draw from the pocket. The larger pistol is a six-shot, and the

smaller a five-shot. They weighed 15.1 and 8.9 oz. empty, respectively.

Carry Options

As often as I’ve encountered these little revolvers, I’ve rarely discovered period holsters for them. Those I have seen are simple leather pockets sewn to a rectangular backing to hold them vertically oriented in the front pants pocket, or gun-shaped pouches made of oil skin (presumably to protect the gun from rain or sweat) that buttoned into the pocket. A third type resembled a pistol-shaped woman’s change purse, which can’t have been of any practical use where an expedient presentation was required.

Even period holster advertisements for this type of revolver are hard to find. My research suggests they were usually just carried in a pocket, with no holster of any kind. My own experience with holster-less pocket carry has shown it to be fairly easy with these small, light guns, though any of them with the firing pin fixed to the hammer could easily discharge if dropped the wrong way. This was a well-recognized risk at the time.

The danger could be mitigated to a degree by rotating the cylinder so the firing pin protruded between cartridge rims. Iver Jonhson developed and patented a brilliant transfer-bar passive safety mechanism to render its pistols drop safe, and their “Hammer the Hammer” marketing slogan was world-famous. Forehand & Wadsworth adopted a frame-mounted, spring-retracted inertial firing pin to make its guns less susceptible to accidental discharge if dropped.

Marketing-Driven Innovation

Perhaps because the value-priced pocket-revolver market was so big, there was a lot of competition and innovation. Patents were important to differentiate brands, boost sales and make manufacturing more efficient to increase profitability. In 1887, H&R patented its bobbed safety hammer, which eliminated the risk of it snagging on clothing during the draw but still allowed thumb cocking for single-action shooting. Hopkins & Allen countered with a patented folding hammer spur.

The exceptionally graceful and well-designed Parker Safety Hammerless revolver had a patented knurled safety wheel at the top of the grip frame that, when activated, prevented the trigger from being pulled. I once bought an excellent example of this rare, higher-end pocket revolver for $75 because the safety was on. The seller, knowing nothing about it, assumed it was broken. Hopkins & Allen patented the Triple Action Safety that pushed the hammer off the firing pin unless the trigger was pulled. They also patented the Hercules Barrel Joint Latch for their break-open revolvers, which was one of the best latches and virtually impossible to accidentally open. It also allowed the rear sight to be fixed immovably to the frame.

Break-open actions cost about twice as much as solid-frame guns but allowed

for faster loading and simultaneous ejection, although some ejected better than

others. For example, the Iver Johnson on top doesn’t lift the spent cases high

enough to get them out of the cylinder without the help of gravity. The bottom

pistol is a hammerless type (actually, concealed hammer) that could be easily

drawn from the pocket and even fired from inside it. It was made by Thayer,

Robertson & Cary of Norwich, CT, between 1901 and 1905 in an attempt to cash

in on the lucrative pocket-revolver market. The company made only a few

thousand guns before closing, making this piece something of a rarity.

Operational Quirks

Most of these revolvers relied on the hand or just inertia to index the cylinder into alignment with the barrel-forcing cone during firing. This was recognized as less than ideal at the time. Misalignment — whether from mechanical wear of the cylinder or it being physically rotated backward as a result of coming into contact with some external object —could lead to misfire or some serious lead spitting with the bullet or pieces thereof going who knows where. Cutouts for the bolt to drop into and lock the cylinder into position prevented this but added complexity and cost. They’re absent from most models, appearing on some but not all of the manufacturers’ better guns.

Solid-frame revolvers universally lacked loading gates. Meaning, if you were aiming up, a cartridge could fall out of the cylinder chamber when it rotated past the opening in the recoil shield and possibly jam the action. Of course, adding a loading gate added complexity and cost to the product. At their price point, the lack of a loading gate was clearly not a deal-breaker for consumers.

A characteristic nearly all these guns share is nickel plating. It served a practical purpose in that it protected the underlying ferrous metal from rust and wear. The main reason it was applied is because it was the easiest way to make a cast iron frame look presentable. Cast iron doesn’t take bluing well. Hopkins & Allen eventually broke from the pack and began using drop-forged steel frames and barrels, but they continued the tradition of nickel plating their revolvers, mostly because they were extremely efficient at electroplating. They actually charged extra for blued guns.

Mass Market Appeal

The popularity of low-priced pocket revolvers seems to run contrary to the contemporary thinking of learned gun people regarding best practices for defending yourself with a handgun. How could this be? I suspect most of the people who bought these guns weren’t gun enthusiasts at all. They just needed to protect themselves, and they didn’t have a lot of money or time to spend on the problem.

Somehow they managed — armed only with a revolver with less than 40% of the power of a .380 ACP, lacking a comfortable, well-designed, inside-the-waistband holster providing both retention and a speedy draw, without advanced self-defense bullet types like the Hornady FTX jacket hollowpoints or Black Hills HoneyBadger and without any training or even range practice. How was it even possible? I’d say because owning one of these little guns addressed the first and most important rule of gunfighting, which is to have a gun! It also happens that these guns were ideally small for concealment and ease of carry, which made folks more likely to carry them instead of leaving them at home. Like all revolvers, they were simple to use —point and pull the trigger. Finally, they were chambered in a caliber that was very easy to shoot well because of its low recoil and as lethal in the long run as heavier-hitting bullets in a time when secondary infections were as deadly as the bullet wound itself. The .32 S&W was a pipsqueak compared to its centerfire peers, but I expect it packed just as much deterrent as a .45 Colt when pointed at a bad guy.

Get more carry options content every other week!

Sign up to receive the Carry Options newsletter.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact