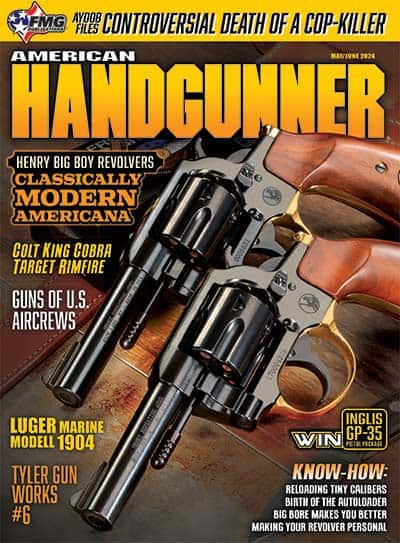

Pistols in the Wild Blue Yonder

Sidearms of U.S. Aircrews

America pioneered the aircraft, and shortly after Americans took flight, they took firearms aloft with them. And while machine guns captured most of the attention, growing ever larger in the amount and the caliber of automatic weapons fitted to flying war machines, airborne Americans never lost their fascination with handguns. From World War I through the Cold War, U.S. pilots chose to carry a pistol with them as they went out to fly and fight for their country.

olonel David Schilling, commander of the 56th Fighter Group, and sixth

leading ace in the 8th Air Force (22.5 victories). The modified full-auto

M1911 was apparently a design created by Schilling. Fellow pilot Hub

Zemke commented that it needed a forward grip as the weapon “sprayed

ammo all over” and that “many a barrel was burned out.”

An Airman’s Choice

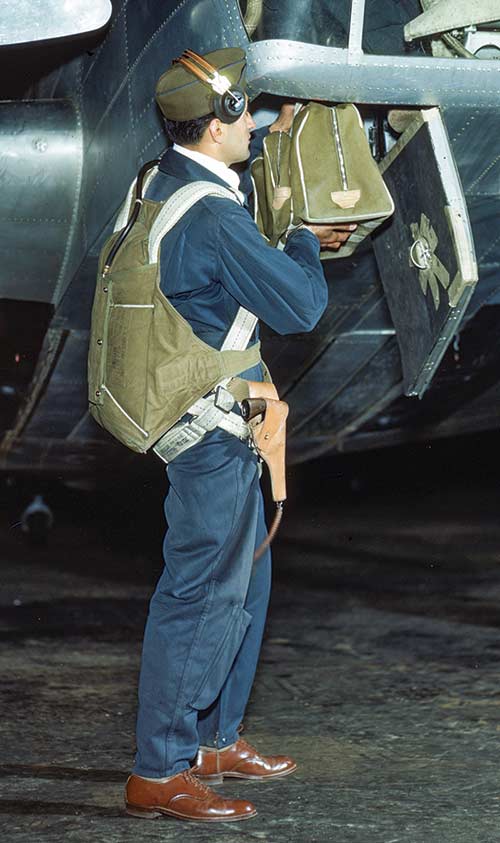

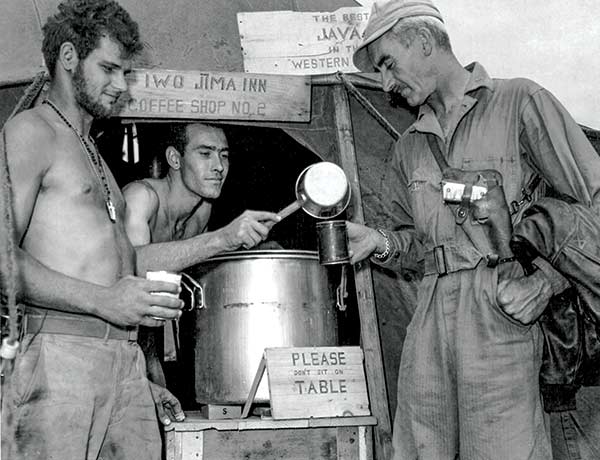

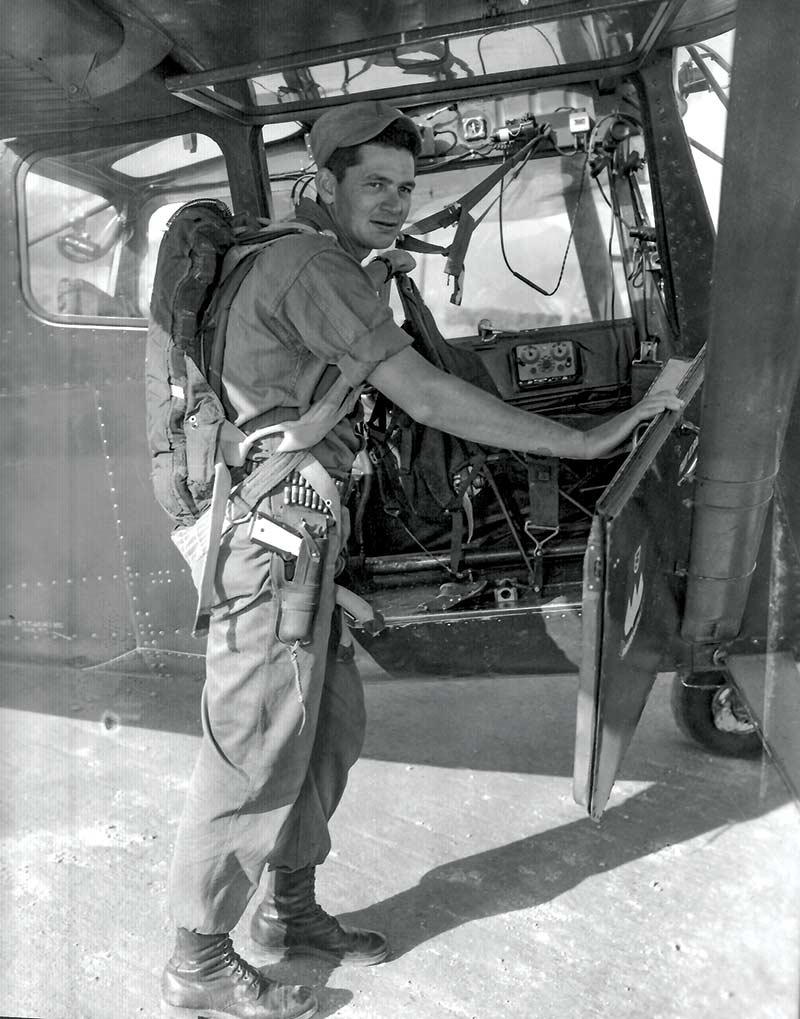

Throughout the 20th Century, U.S. pilots and aircrews were often issued handguns before combat missions or when flying over inhospitable territory — based on the perceived dangers from the residents in that region, human or otherwise. Ultimately, it was a personal choice. The cramped cockpits, turrets and fuselage positions offered little room for a man to maneuver, particularly with a handgun on his hip or over his shoulder.

By the time America joined World War I in April 1917, the pistol had been replaced as an air-to-air weapon, except in the most extreme circumstances. Even so, the U.S. M1911 had been specifically altered to serve as an aerial weapon. A rare modification to the .45 caliber automatic provided the big handgun with a 20-round extension magazine along with a curious cage-like spent-casing catcher. Intended for use with early “pusher” type aircraft with a rear-mounted engine, the cage prevented the spent cartridge from sailing back through the slipstream to strike the propeller in the rear. In those early days of military aviation, a man could even shoot down his own fragile aircraft if he wasn’t careful.

Limited Options

Officially, U.S. aircrews had few choices when it came to handguns. During World War II, a significant number of M1911 .45 caliber pistols were available to U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) personnel. M1917 .45 caliber revolvers are sometimes seen with USAAF men during the war, but this is rare. Both the .45 caliber handguns could be uncomfortably large and heavy in the tight confines of a cockpit, a bomber’s gun turret, or any of the close quarters of a WWII aircraft. The M1911 was available in far fewer numbers for Marine Corps and U.S. Navy aircrews. Naval aviators often flew with the S&W “Victory Model” revolver, chambered in .38 Special. The Victory Model (an S&W military contract version of their M&P Revolver) weighed just 34 oz. unloaded, and the lighter and shorter revolver proved to be a favorite for Navy and Marine pilots.

Some pilots preferred to carry small handguns they purchased privately or acquired via trade in the combat zone. These could be almost any make or model, but in the ETO, pilots (just like almost everyone else) were particularly keen to get a P08 Luger, P-38 Walther, or possibly a .32 caliber pistol like the Mauser 1914, Walther PPK, or the Sauer 38H. As desirable as the German trophy pistols may have been, a lack of familiarity with the firearm, as well as a ready supply of ammunition, kept most of them in the footlocker and on the ground.

Why Carry A Pistol?

With all the complexities of their job, carried out in a fast-moving but rather cramped environment, why would U.S. aircrews even bother with strapping on a handgun? One simple reason is that Americans like pistols, and they feel comfortable carrying them. There may be ample logic that carrying a pistol aboard a military aircraft is unnecessary — but that does not surmount the airmen’s emotional decision to carry for personal defense. My father was a WWII combat veteran, and his attitude about firearms answers the question pretty well: “Better to have it and not need it than to need it and not have it.” For those airmen who chose to carry a pistol, they believed it made a difference, and that difference might just mean their life.

Not all threats for a downed pilot came from human enemies — depending on where the plane came down. Snakes, sharks and various large predators made no distinction about the uniform a man wore. Some pilots, particularly in the Pacific Theatre, feared capture by the Japanese more than death. In that case, a pistol could provide a quick and painless end compared to inhumane captivity and brutal torture.