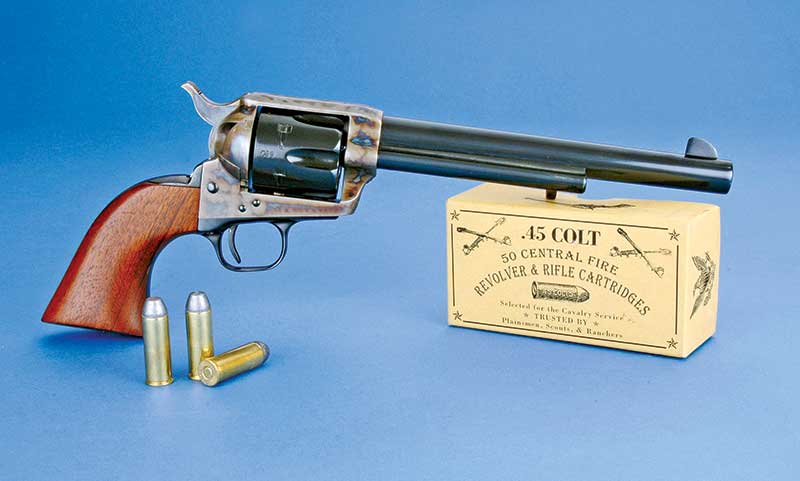

The .45 Colt

History And Surprising Facts About This Iconic Cartridge

About a decade ago I caused a considerable stir in Handgunner’s pages by writing I didn’t particularly like the .45 Colt as a smokeless powder cartridge. And I still don’t. The .45 Auto-Rim is better with smokeless in standard-sized revolvers.

I have nothing but respect for the .45 Colt as it was developed originally in the black powder era. For the purposes for which it was intended nothing beat it back then. Be sure of this, the .45 Colt and its introductory revolver were developed with one purpose in mind: to be the sidearm of horse-mounted troops. Its big bullet was intended not only to knock down human adversaries but also for putting their horses out of commission.

To that end the government testers developed a cartridge case longer than any other made before. It was 1.29″ long as opposed to 1.10″ for the .44 Colt or 0.91″ for the .44 S&W American. Those two are used as examples because between 1871 and 1873 the US Army purchased 1,000 Smith & Wesson Model #3 and 1,200 Colt Richards Conversion revolvers chambered for their respective companies’ .44’s. Both of those rounds used about 210-gr. bullets (sources vary) over 23 to 28 grains of black powder (again sources vary).

For decades, many firearm magazines have listed 40-gr. of black powder as the .45 Colt military load used. Except that’s not true. In developmental testing, some 40-gr. charges were tried but proved too much for the wrought iron frames of early Colt revolvers. The .45 Colt loads produced by the US Government’s Frankford Arsenal used 30 grains of black powder. Also commonly written is that early .45 Colt loads used 255-gr. bullets. Wrong again. They were 250-gr. conical bullets with two lube grooves and a hollowbase.

More Errors

Here’s something else commonly written: “Colt initially named this new handgun the Single Action Army.” Oops … not so. In the beginning it was called the New Strap Pistol — the strap being the top strap connecting the two parts of the frame. I’m hoping someone is mentally asking, “Why did Colt begin incorporating a topstrap with this model?” It was because the big .45 bullets whacked into barrel forcing cones so hard they actually bent the front of the frames. The top strap stopped the bending.

Those early Frankford Arsenal .45 Colt loads were made with copper cases — not brass. Primers were centerfire, but held inside the case. Due to those two factors government .45 Colts were not reloadable. Early in the 1880’s the switch was made to brass for cases, and changed to outside priming. After that the army began assembling and issuing reloading kits to troops so they could actually have enough ammunition for meaningful practice.

All government-purchased Colt .45’s were the same: color case-hardened frames and hammers with the rest of the metal blued. All had 71/2″ barrels, grooves down the topstrap for rear sight and a rather small blade front. Grips for all were one piece — truly cut from one piece of walnut. The grip frame consisted of two pieces, the backstrap and the triggerguard, and the wood inletted so those items fit around it.

The backstrap and triggerguard were held to each other and to the main frame by six screws. And that’s probably the reason each New Strap Pistol was sold to the government with a screwdriver as part of the purchase price. You can beat a Colt single action every which way and it will still work, but those six screws have to be kept tight.

Army Inspectors

US Army officers served as inspectors, stationed at the Colt factory. They were equipped with sets of gauges, plugs and measuring instruments. Somewhere during manufacture, revolvers intended for the government got a “US” stamped on the frame’s left side under the cylinder. That did not automatically mean the Colt was accepted. When one was deemed good enough the inspectors stamped a “cartouche” containing their initials into the left side of the walnut grip.

There exist early Colt .45’s with the “US” stamp but with nickel-plated finish and ivory grips (one piece also). The story there is inspectors were very finicky about what they stamped their initials into and Colt considered some of their rejections as viable sales items. Thus they were finished and fitted with grips and then sold on the civilian market.

Changes

Just when the US Army had gotten things just right — an outstanding handgun with new powerful cartridge — they went and made things “more better.” There were behind the scenes shenanigans going on too lengthy to detail here, but the upshot of it all was in 1875 the army adopted another .45 revolver. It was the Smith & Wesson Model #3 with the addition of a Major Schofield’s patents. Part of the shenanigans was that Major Schofield’s brother was a serving Major General.

The cylinder of an S&W Model #3 “Schofield” is 17/16″ long. Colt .45 cartridges are too long to fit, and also the .45 Colt’s negligible rim would not work with the Model #3’s star extractor. (That lack of rim was why early lever guns were not chambered in .45 Colt as it would not work reliably in the action.) So Smith & Wesson developed their own .45 cartridge with a 1.10” case and 0.020″ wider rim. As loaded by the Frankford Arsenal this .45 carried a 28-gr. powder charge under a 230-gr. bullet. The case was still copper and the primer was still inside it.

This enticed the bright lights serving on the US Army’s Ordnance Board to adopt Smith & Wesson’s new .45 as “substitute standard.” Like the Colt, those S&W’s sold to the army were all alike. Barrels were 7″ long, the finish was blue except for the triggers and hammers, and the grips were two-piece walnut. They were also inspected and “cartouched” like Colts although rejection rates were much lower at the S&W factory.

At the time, US horse soldiers throughout the country could have been armed with two distinctly different .45 handguns, and supply officers had to keep sorted which units had which handguns so they could send the proper cartridges to them. Longer .45 Colt rounds would only fit in Colts’ revolvers, but Smith & Wesson’s shorter .45 would work in both. It was a no-brainer which one would stay and which one would go. At least that was the situation until the early 1880’s when Smith & Wesson revolvers and their ammunition were dropped entirely from government service.

Every company making “large-frame” revolvers in the late 1880’s offered them as .44-40’s. No other company made their sixguns for .45 Colt. Remington did make a few test guns but they were not cataloged.

As with most firearms and their calibers adopted by the US Army, Colt’s .45 became immensely popular on the civilian market. It was the handgun and cartridge by which all others were judged.