Walther P38

The Most Influential pistol You Don’t Think About

The Walther P38 wasn’t the first 9mm: The honor goes to the P08 Luger which, like later German service pistols, mostly came to the U.S. in the rucksacks of returning GIs. Though its sleek lines still beguile, the Luger is a mechanical dead end while the P38 has shaped the modern service pistol.

Nor was it the first double action: The PP or the obscure .32 caliber Little Tom usually get credit for that. Walther’s pistols, though, starting with the blowback PP in 1929 and quickly followed by the smaller PPK, were the first commercially successful ones, and the P38 adopted by the Germans in 1938 was the first 9mm military handgun to combine DA/SA with a locked breech.

Action!

an the American M1911 whose single action trigger has always bedeviled the fool and incautious alike, the P38 was a far cry from the ridiculously hard to make toggle-action Luger. Among other things, it incorporated inexpensive stampings — groundbreaking technology pivotal to later guns like the HK G3/MP5 family.

Instead of the mechanism having to stay cocked to be ready to fire, as with single action or striker-fired guns, the hammer of the P38 stayed in the forward position until the trigger was pulled, which both cocked and then released the hammer, which was cocked by the cycling of the slide for subsequent shots. Hence the DA/SA name; double action first shot, single action thereafter. Applying the safety automatically dropped the hammer, returning the gun to DA mode.

2 Steps Forward, 1 Back

The heel magazine release securing the P38’s single-column, 8-round magazine was a step backwards from the pushbutton of the PP/PPK family, as was a safety change where the hammer falls onto a locked firing pin instead of the safety cross shaft on the PP family. Unfortunately, the square early firing pins were fragile, and one breaking when the hammer fell on a loaded chamber would be spectacularly dangerous, as the gun would likely dump its entire mag. Breaking one on an empty WWII-era gun is safer, but as I learned the hard way, expensive. The later round pins are stronger.

Like the PPK, P38 grips are wraparound plastic ranging in color from brown and green to black, and at times made of sheet metal due to the exigencies of war. We were, after all, bombing the foolishness out of any German manufacturing facility we could fly over at the time. With memories of trench warfare still fresh, the grips were grooved horizontally so they would readily shed mud, a calculus omitting how much slicker that makes the grip. Later ones are checkered.

The loaded chamber indicator of the pocket pistols was retained, as was the clever plunger-retained extractor debuted on the Walther Model 8.

Silencer Ready

Instead of the customary Browning-style tilting barrel, the P38 barrel slides forward and aft in recoil, with a locking block beneath the barrel that rotates up into locking notches on either side of the slide. Unique, and, like the DA system, one of a precious few handgun features not invented by John Browning. Mostly important for suppressed guns, this eliminates the cantilever effect where the added leverage of a suppressor’s weight keeps the rear of a tilting barrel locked up into place and unable to cycle.

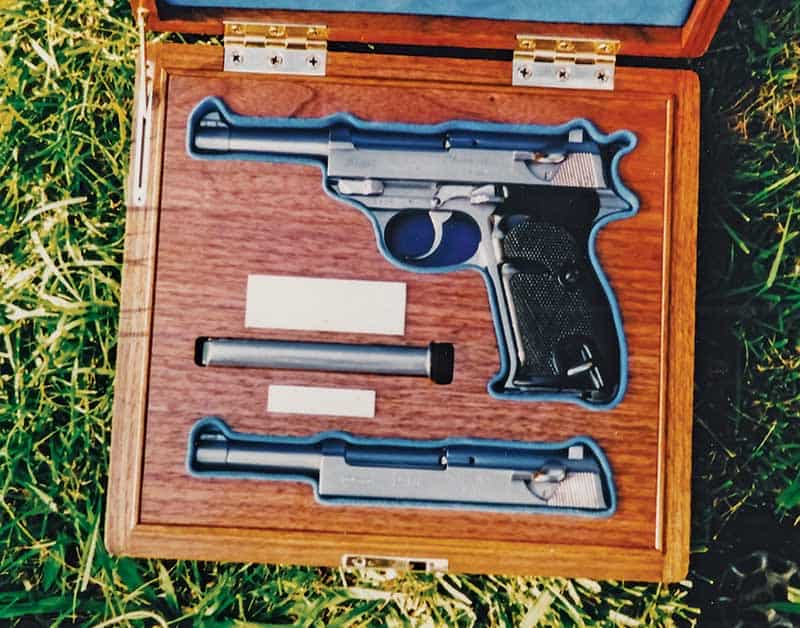

Walther produced suppressed versions of the P38s, some with an added latch to keep the slide shut during firing, as well as the slightly shorter P4 and snubnosed P38K (both of which omitted the problematic slide top cover), and the alloy-framed P1 adopted by the West German Bundeswehr and the closed-slide P5 and P5 Compact. Given the Germans’ well-founded fascination with subcaliber conversions, the P38 was made in .30 Luger and .22 LR, with conversions in .22 LR and 4mm. The 4mm was available until recently from Lothar Walther, the still active barrelmaker founded by Carl Walther’s son.

Inspirations

Walther wasn’t the only one riffing on their proven design. British stalwart Webley & Scott promptly made a DA 9mm in 1952, as did S&W, whose Model 39 appeared in 1954, followed by the hi-cap 59 that later morphed into the hugely successful 5906. A rare military version of the 39, the Navy’s Mk 22 Mod 0 “Hush Puppy,” was equipped with a suppressor very similar to Walther’s, further revealing the gun’s inspiration.

Nor was that the end of the P38’s influence: The Army’s General Officer Pistol program supplied distinctive sidearms to flag officers as a sign of rank. Originally using Colt pocket pistols in .32 or .380, the supply was depleted by 1972. Two of the four proposed replacements were the P38 and M39, already in use by Air Force Officers. A third contestant was a 9mm Colt Commander. While the test was won by the M15 arsenal-shortened M1911 .45 — the only one that wasn’t a 9mm — the pistols under consideration make it clear what was on the military horizon.

Beretta Derivations

Beretta’s first riposte to the P38 was in 1951 with the M51, also known as the 951 and produced elsewhere as the Helwan Brigadier. It included the P38’s wraparound grooved grips (as did the roller-locked CZ52) and locking block. Other than in Beretta and its Taurus copies, the über rare Korth semi-auto and a couple of stray Llamas, this locking system appears virtually nowhere else, leaving no question where the idea came from. Visually, the 951 combines the Beretta 1934 and sleeker, Mossad-famous Model 70, including their single action triggers, scooped-out slides and the low grip-mounted magazine release of the 70. Not an unattractive pistol, the 951 is primarily interesting as a transitional piece between the P38 and its most triumphant progeny, the 92.

Adopted by the U.S. Army in 1985 as the M9, the 92 arrived in 1976, replete with a P38 locking block and DA/SA trigger mated with the high-capacity magazine first seen on the Browning Hi-Power P35. One could be forgiven for saying the 92 is a P38 with a P35 magazine. The inspiration is clear, and while it won’t latch, a 92 mag manually held in a Hi-Power magwell will feed.

P38 Legacy

While the peerless John Martz produced stunning custom P38s, including cut-down “Baby” versions and .45 ACP and .38 Super versions painstakingly created from two pistols each, P38’s true legacy is the service pistols inspired by its combination of DA/SA trigger and 9mm chambering. This pairing set the standard for the 92 as well as other police and military pistols including SIG, HK, Ruger and the other Wondernines that ruled the roost through the ’80s and ’90s.

Not to mention the caliber, arguments continue, as they have for the century-plus since Thompson and LaGarde first tested the 9mm versus .45. The 9mm is currently the chambering for military, police and increasingly, concealed carry. The Luger started it, but let’s not forget when the Luger was under consideration by the Army, Ordnance insisted it be in .45 ACP. It’s the P38 and its progeny that popularized 9mm in the U.S.

With over a million produced during WWII, not counting pre- or post-war guns, there are plenty around, including the reasonably priced alloy framed P1 versions. A vast library of books covers the P38, from the two-volume Walther: A German Success Story to Maj. George Nonte’s fascinating little manual that includes helpful field expedients such as how to urinate through the action (“vigorously”) to rinse debris from it, an indignity the old warhorse doesn’t deserve.