What's A Fitz Special?

Yesterday’s cutting-edge gun designs of tomorrow

In today’s world of readily available, off-the-shelf pocket pistols that are easy to conceal and convenient to draw, it’s hard to imagine a time when this wasn’t the case. In the early 20th century, one man made it his mission to fix this problem. The end result was a now-iconic modification bearing his name and, eventually, a new gun altogether: The Colt Detective Special.

John Henry Fitzgerald was a man of many talents. He was a police officer, competitive shooter, gunsmith, author, expert witness and an employee of Colt from 1918 until his death in 1944. During that time, he lamented the fact most revolvers on the market were built on large frames with long barrels. They were good for competition and police work, but didn’t lend themselves well to concealed carry and defensive use by civilians.

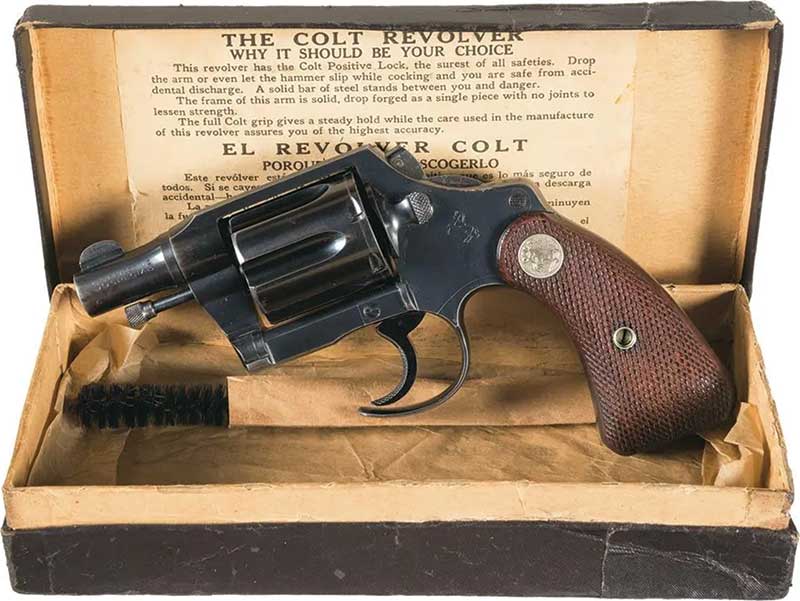

To make the large-frame revolvers so prevalent on his workbench at Colt more conducive to defensive use, he performed major surgery on the guns. This involved shortening the barrel to 2″ or less, bobbing the hammer, shortening and/or rounding the butt, shortening the ejector rod and removing the front of the trigger guard.

According to John, his gun was ideal in defensive situations. The bobbed hammer prevented snagging on clothing when drawn from concealment. If attacked while seated in a car, the short barrel cleared the steering wheel more easily. The most interesting claim, however, related to contemporary ammunition. Such a short barrel was unlikely to become blocked by a squib load, not an uncommon occurrence at the time due to lack of quality control.

Fitzgerald’s modifications soon became his hallmark, and the guns he modified were known as “Fitz Specials.” Originally done on Colt’s Model 1917 and New Service revolvers, John eventually began modifying the smaller Police Positive and Police Positive Special models, which lent themselves to the task more easily.

Eventually, the idea behind the modified guns was embraced and the Colt Detective Special was added to the standard catalog in 1927. It was the first revolver offered directly from the factory with a 2″ barrel that wasn’t a special order. In time, other manufacturers, too, began offering these new “snubby” guns with short barrels, bobbed hammers and rounded butts.

Keeping Perspective

When evaluating the merits of Fitzgerald’s design, we must be careful not to judge it by today’s standards. There’s no denying the benefits of a short barrel, bobbed hammer and a smaller, rounded grip. These are common features on many of today’s popular concealed carry revolvers.

The removal of a portion of the trigger guard is regarded today as unsafe, but this wasn’t the case when Fitzgerald began working on his guns in the 1920s. It has been noted some undercover officers from the era did this to their guns to enable them to fire more easily while wearing winter gloves and through coat or pants pockets. Therefore, what Fitzgerald was doing was not seen as unsafe

or unprecedented.

Factory records from Colt reveal at least two of these modified guns were sent directly to law enforcement. One to the Des Moines (Iowa) Police Department, one to the Lincoln (Neb.) Police Department and another to the Pennsylvania State Police.

The design relied on the long, heavy double-action trigger pull and the slight protrusion of the trigger guard beyond the end of the trigger to keep the gun safe while being carried and drawn. By this logic, the gun only fired when it was deliberately drawn and a finger had been placed on the trigger.

Some famous (and infamous) historical figures were known to have carried Fitz Specials. Colonels Charles Askins, Rex Applegate and Charles Lindbergh all carried one, as well as Clyde Barrow — Bonnie Parker’s beau. Askins wrote Fitzgerald a letter, praising the modifications, calling the Fitz Special the “grandest defense gun I have ever had … it was a whiz for the purpose intended.”

Because Fitzgerald modified the guns himself when he worked at the Colt factory, not all of them were documented in the factory records as having received the custom work. This means the exact number made by Fitzgerald will forever remain unknown and debated, with estimates ranging from as few as 40 to as many as 200. Regardless of how many he made, the number of known and surviving guns stands at less than 20.

With so few genuine Fitz Specials in circulation, they command a premium among collectors. Many guns dating to John’s time at the Colt factory have turned up in the Fitz Special configuration, but the only way to know if it’s genuine is with a factory letter — and that’s a roll of the dice. On average, you can expect to pay $6,000–$8,000 for a verified Fitz, but they can go much higher if associated with someone important, even if the work wasn’t done by John. For example, Clyde Barrow’s Fitz Special cannot be documented to John Fitzgerald, but because of the Bonnie and Clyde connection, it sold in 2014 for more than $48,000.

Subscribe To American Handgunner

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: