Lessons From A Gunfighting General

Situation: A senior officer personally kills 30 of the enemy on the battlefield … and some more people elsewhere.

Lesson: Great men often have great strengths and great weaknesses … and skill at arms can be as much a life-saver in the civilian world as in the military.

“There is much to dislike about Nathan Bedford Forrest; there is also a good deal to admire,” wrote Brian Steel Wills in his introduction to A Battle From the Start (p. xix), the more acclaimed of his two biographies of the Confederate general.

Another author, Jack Hurst, divided the five main parts of Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography according to what he saw as the stages of his subject’s life: Frontiersman, Slave Trader, Soldier, Klansman … and Penitent. He said, “What sort of man did all this? By most accounts, two different ones: a soft-spoken gentleman of marked placidity and an overbearing bully of homicidal wrath” (Hurst, p. 6).

Forrest being born in a log cabin, becoming man of the house and providing for his family when he was a boy, is a story better suited to Reader’s Digest than American Handgunner. That he earned great wealth young, becoming a millionaire in mid-19th century dollars in an occupation even most Southerners of the time held in low esteem, I’ll leave to Bloomberg Business. His involvement with the Ku Klux Klan in its formative years, and his vehement repudiation of what the organization had become (which consumed much of his last years) would fit better in a sociology journal than a gun magazine.

It is the middle ground, the years of the American Civil War, we’ll focus on here. In macrocosm, whether they called it The War Between the States or The War of Northern Aggression, friend and foe and impartial outside observers alike considered Forrest one of the all-time great battlefield commanders.

For our purposes here, in microcosm, we’ll focus what allowed him to survive personal combat against sometimes overwhelming odds, just as he defeated better-equipped Union forces twice or more the size of his own.

We’ll focus also on the fact he was the rare general who had been a gunfighter before he put on a uniform, and was an armed citizen not only before the war, but after, when he killed a man and was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

Before the War: First Blood

In 1845, a 24-year-old Bedford Forrest went to Hernando, Miss., to visit his elderly uncle, who was having trouble with a family named Matlock. In the town square near the uncle’s place of business, he encountered three of the Matlocks and one of their associates, who had plainly come to “settle the score.” Forrest explained it was none of his affair, but he wouldn’t stand idly by while his aged relative fought a lopsided battle with four angry younger men. The opposing party drew and opened fire on Bedford Forrest, one bullet missing him and killing his uncle as he stood in the doorway of his business.

A contemporary account in the Memphis area newspaper American Eagle said the young Forrest “immediately drew a revolving pistol and set it to work as fast as possible, shooting both of the Matlocks through; the younger T.J. through the shoulder and the upper part of the breast, and the other through the arm, which has since been amputated.” By all accounts, Forrest had only two cartridges loaded in his handgun, and after scoring with both and running dry, a sympathetic bystander tossed him a Bowie knife with which he charged what remained of the Matlock group, who fled.

Not long after, he was with lawyer James Morse when one of the latter’s enemies, James Dyson, shot and killed Morse with a single blast from a double-barrel shotgun. Forrest drew and cocked a handgun and leveled on Dyson saying “two could play the game.” The man lowered his gun and surrendered to face trial for murder, later saying he gave up because he didn’t think the one charge of buckshot he had left would be enough to keep Forrest from killing him. As a result, Forrest was later elected constable of Hernando and coroner of DeSoto County.

Against The Enemy

When the war broke out, Forrest enlisted at the rank of private and quickly rose in the ranks, initially perhaps because he used his own wealth and influence to recruit and equip a body of mounted troops, though his subsequent rapid promotions seem to have been due entirely to his battlefield performance. The fact he engaged in hand-to-hand combat alongside his men won the respect of the grunts and the Confederates’ supreme commander alike. After the war, when asked who he thought was the best general on either side of the conflict, Robert E. Lee answered, “A man I have never seen, sir. His name is Forrest.”

Leading from the front can carry you into the enemy’s midst prematurely, Forrest discovered more than once, the first time on December 28, 1861 in Kentucky. Writes Wills on page 5, “Forrest suddenly became engaged in a desperate fight with three opponents — a private and two officers, Captains Bacon and Davis. As his horse carried him past, he shot the Union trooper and, leaning forward in his saddle, managed to elude the saber thrusts of the two officers. Riding on beyond them, he pulled up and swerved in the saddle.

As Forrest turned, a Confederate private, W.H. Terry, rode up to help him, drawing Davis’ attention. Terry’s action gave his colonel the precious seconds he needed, but cost Terry his life. Forrest then sped back, mortally wounding Bacon and disabling Davis when his horse collided with the Union officer’s, separating Davis’ shoulder.”

History repeated itself for the Confederate commander at the Battle of Shiloh, in April of 1862. Rushing ahead of his troops on horseback, Forrest again found himself surrounded by Union infantry. “One bold Union soldier pressed his rifle muzzle against Forrest’s side and fired. The ball penetrated Forrest’s side and lodged against his spine. But in an instant, the Confederate commander turned his horse and broke free of the pack of angry Federals. As he rode clear, he grabbed an unsuspecting opponent and hoisted him onto the horse behind him. With the soldier as a shield, Forrest rode back to his waiting men, dumping the hapless rider when he got out of range” (Wills, p. 70).

Some historians are skeptical of the claim the General swept a union soldier off his feet and used him as a human shield, though conceding every other element of the account is genuine. Others totally believe it, pointing out in all such versions of the story the Union soldier is an unusually small man, and Nathan Bedford Forrest stood a brawny six-feet-two and was described by all who knew him as being unusually strong physically, not to mention what adrenaline can do for an outnumbered combatant surrounded and under fire.

No one ever accused Nathan Bedford Forrest of being a slow learner, but even the most hard-earned lesson can be forgotten in the red haze of anger and vengeance. Early in 1864, Forrest’s beloved younger brother Jeffrey, who had ridden with him for most of the war, was killed by a Union bullet through the neck. Filled with grief and rage, Forrest galloped furiously toward enemy lines. The surgeon, Dr. J. B. Cowan, who accompanied Forrest on the battlefield, rode after him and Wills recounts, “He ‘came upon a scene which made my blood run cold.’ Forrest and part of his escort had plunged into a line of Federals who were attempting to form as a rearguard of sorts. Cowan could see them in the road ‘in a hand-to-hand fight to the death’” (p. 164). Wills continues, “according to one account (Forrest) personally dispatched three men in the few moments of close-hand fighting” (p. 165).

The final such incident occurred near the war’s end, at the Battle of Ebenezer Church, shortly before Forrest’s ultimate defeat at Selma and subsequent surrender. Biographer Hurst quotes a Confederate cavalryman, Capt. John Eaton of Forrest’s escort, on the Ebenezer Church fight: “Each of us was armed with a pair of six-shooters, and I emptied the 12 chambers of my two army-pistols … not … more than five paces from the Federal trooper at whom it was aimed.

It seemed as if these fellows were bent upon killing the general, whom they recognized as an officer of high rank. I saw five or six slashing away at him with their sabers at one time.” Lt. George Cowan said one saber slash “struck one of his pistols and knocked it from his hand. Private Phil Dodd spurred his horse to the general’s rescue, and shot the Federal soldier who was so close upon him, thus enabling General Forrest to draw his other pistol, with which he killed another of the group” (Hurst, p. 250).

In the course of that same battle on April 1, 1865, Forrest fought to the death with Union Captain James Taylor. Much later, he would tell Taylor’s commander, “A young captain of yours singled me out at Ebenezer Church and rained such a shower of saber strokes on my head and shoulders I thought he would kill me. While warding them off with my arm I feared he would give me the point of his saber instead of the edge, and had he known enough to do that, I should not have been here to tell you about it” (Wills, p. 309). Forrest killed Taylor with a one-handed shot from one of his Navy Colts. Wikipedia currently says Taylor was the last man Forrest killed, but Wills says this happened instead shortly thereafter in Selma, where “In this fighting, Forrest killed the last Federal soldier attributed to him — the 30th man he killed in personal combat during the war” (Wills, p. 310).

No serious historian disputes the count of 30 Union soldiers personally slain by Nathan Bedford Forrest, one-on-one, nor do they dispute some 29 horses were shot out from under him in heavy combat, nor that he was wounded himself several times. Rather, the number 30 — always applied to blue-clad combatants — understates the number of lives he personally ended.

At times, Nathan Bedford Forrest killed men wearing butternut gray as well as Union blue.

Killing His Own

The first authoritative biography of Nathan Bedford Forrest appears to have been written by a fellow Confederate cavalryman, and published in 1899. In That Devil Forrest, John Allen Wyeth wrote, “To his mind the killing of one of his own soldiers now and then, as an example of what a coward might expect, was a proper means to the end. At Murfreesboro, in 1864, he shot the color-bearer of one of the infantry regiments which stampeded, and thus succeeded in rallying the men to their duty. At Brentwood he did not hesitate to do the same thing in the effort to check some panic-stricken Confederates” (Wyeth, p. 571).

At the Masonic building in Columbia, Tennessee on June 13, 1863, he was shot by Confederate Lt. Andrew Willis Gould, who the previous April 30 at the battle of Sand Mountain, had left behind a cannon when forced to retreat. Forrest had considered it cowardice and ordered him transferred. (One of the general’s trademarks was “flying artillery,” a horse-drawn cannon that rode with his cavalry, and he had proven it to be a decisive battlefield strategy.) The two men argued over this in Columbia; witnesses said Gould fumbled for a gun in his pocket and it discharged, perhaps through the pocket, striking Forrest above the hip. Forrest grabbed Gould’s now-drawn gun and, with his other hand and his teeth, opened a folding pocket knife and drove it into Gould’s side. The Lieutenant fled.

Other officers hustled the general into the office of a nearby doctor, who told him an abdominal wound in the heat of summer was likely to turn mortal. Forrest was heard to shout, “No damned man shall kill me and live!” Seizing two revolvers from one or more subordinates, he tracked the badly hurt Gould to a nearby tailor shop and chased him outside, firing. He missed, and a ricochet wounded a bystander. Gould collapsed outside. Witnesses said the general contemptuously prodded the downed lieutenant with his boot, then turned and strode away. Further examination proved Forrest’s wound to be relatively minor, but Gould died of his knife wound two days later. In the interim, legend has it General Forrest went to Lieutenant Gould’s deathbed, where they tearfully apologized to one another.

In the one case, the Gould killing was clearly self-defense, and treated as such. The other? Today, an officer shooting one of his own soldiers fleeing a battle would result in a court martial, notwithstanding the fact contemporary Confederate cavalryman Wyeth seemed to feel the end justified the means. But let’s look at two other shootings imputed to Forrest. From Wills, on pages 76-77: “The record clearly indicates Forrest personally killed one black man at Murfreesboro, although his biographers have presented the story with various degrees of detail and accuracy. The earliest of these biographers, Thomas Jordan and J. P. Pryor, described the incident more clearly. According to them, as Forrest rode through the camps of the Minnesota troopers, a ‘negro camp-follower’ fired at least five times in an effort to kill the Confederate officer, before Forrest shot his assailant ‘with his pistol at the distance of 30 paces.’”

Justifiable under the circumstances? Few could argue otherwise. But consider this, from the same source: “ …Union Major General D. S. Stanley suggested to readers of the New York Times Forrest was involved in another more cold-blooded killing at Murfreesboro. Stanley attributed the story to ‘a rebel citizen of Middle Tennessee, a man of high standing in his community, who had it from his nephew, an officer serving under Forrest.” The account read, “A mulatto man, who was the servant to one of the officers in the Union forces, was brought to Forrest on horseback. The latter inquired of him, with many oaths, what he was doing there. The mulatto answered he was a free man, and came out as a servant to an officer, naming the man. Forrest, who was on horseback, deliberately put his hand to his holster, drew a pistol, and blew the man’s brains out” (Wills, pages 76-77).

If ever a set of circumstances would allow for a murder indictment, it would have been this one. Even in the 19th Century, there was no statute of limitations for murder, and Forrest being as hated as he was by victorious Northern forces, the absence of such an indictment indicates the “I heard it from a guy who heard it from his nephew” element was not taken seriously by authorities North or South.

But Forrest himself famously said “War is killing,” and we can’t talk about him and killing in the same breath, without discussing what history remembers as the Fort Pillow Massacre.

Fort Pillow

On April 12, 1864, Forrest’s forces surrounded Fort Pillow, 40 miles north of Memphis and when the Union commanders did not surrender, attacked. His men overwhelmed the fort and a massive slaughter ensued, after which Forrest himself said the river by the fort ran red with blood for 200 yards. Roughly half of the garrison was black Union troops, a disproportionate number of whom were killed, and there were claims many if not most were slain while attempting to surrender. It became a national scandal of similar proportions to the My Lai incident in Vietnam more than a century later, and blame was laid squarely on Forrest.

However, there was also credible testimony some among the slain were shooting at the Confederates when the latter returned fire, and the Union commanders had not, after all, surrendered. There was also testimony Forrest himself ordered the cessation of shooting, and at one point stood between his own forces and the Union troops with revolver in one hand and saber in the other. One account even has him shooting a Confederate soldier who disobeyed his order to cease firing. Suffice to say even though the mood of the times would have had Forrest swinging on a noose like a Nazi war criminal after the Nuremburg trials 80 years later had proof been there to convict him, he was never brought to court for anything to do with Fort Pillow.

After The War: Last Kill

At the end of the war, Forrest returned to a plantation where black subordinates were remunerated workers instead of slaves, he having freed his own slaves before the Confederacy’s surrender. It came to his attention one of those men, Thomas Edwards, was viciously beating his wife. Forrest went to Edwards’ cabin and told him such behavior would not be tolerated on his property. Edwards replied he would beat his wife whenever he wanted, and drew a knife; Forrest, apparently unarmed, grabbed a broomstick and hit Edwards with it; Edwards, according to testimony, came at him with the knife, inflicting a minor wound; and Forrest picked up an axe in the cabin and struck Edwards once in the left side of the head, killing him instantly. Forrest was tried, charged with murder, and on March 31, 1866, was acquitted on all counts by the jury. It was his last armed encounter. He died in bed of natural causes on October 29, 1877 at the age of 56.

Much later, a biographer would write, “General Richard Taylor, in his entertaining book Destruction and Reconstruction, says, ‘I doubt if any commander since the days of the lion-hearted Richard killed as many enemies with his own hand as Forrest’” (Wyeth, p. 570). We cannot help but note he was an armed citizen in his first gunfight at age 24, and an armed citizen in his last justifiable homicide once the war was over.

Lessons

We don’t learn morality lessons from a slave-trader and avowed racist, but combat survival lessons can be learned from Nathan Bedford Forrest.

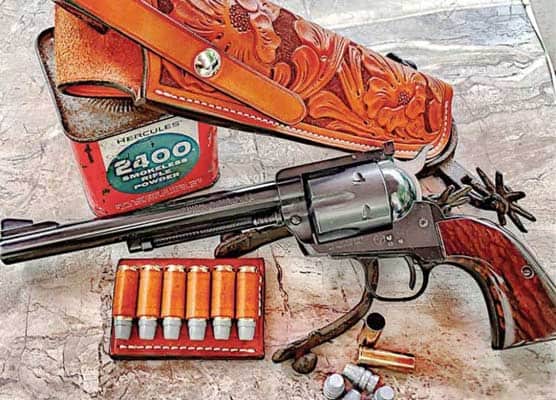

Choose your weapons wisely, and develop skill with them. Albert Castel, writing the foreword for the current edition of Wyeth’s biography of Forrest, wrote on p. xxi: “Although he hacked down a large number of antagonists with his razor-sharp sword, thanks to his strength, size, and ferocity, he considered revolvers far more effective for hand-to-hand fighting and so retained sabers in his command only for officers as a badge of rank.” Wyeth himself says the General’s favorite weapons were .36 caliber “Navy sixes,” and records show on July 20, 1861 he purchased from his own pocket a large consignment of weapons and accoutrements for the troops he had assembled including “500 Colt’s navy pistols.”

His skill in wielding all of those weapons is made obvious by history. In one battle near Memphis, Forrest came upon a Union man about to kill a Confederate who had run out of ammunition, and he saved his comrade’s life by nearly decapitating the Northerner with a swing of his saber. I can find but one case in which Forrest killed an enemy with a long gun: In February of 1862, he spotted a Union sniper in a treetop and, commandeering a Maynard rifle from a nearby Confederate trooper, sent the sniper tumbling to the ground dead with a single shot.

Be armed and ready. It’s amazing a warrior like Nathan Bedford Forrest was unarmed in time of war (albeit in what he thought was a secure place) when one of his own disgruntled subordinates shot him. It is surprising when he went to confront a man he knew to be a violent wife-beater, he wasn’t carrying a gun. The bullet he took from his lieutenant and the knife wound he sustained from Edwards in his last death battle are timeless lessons for us all. The pocket knife he’d been using to pick his teeth shortly before the first such example, and the axe he was lucky enough to reach in the last, may not be there for the rest of us if and when we face such attacks.

“Get there the fustest, with the mostest.” This saying attributed to Forrest in the rural Southern dialect of the day, actually seems to track to something General Basil Duke wrote of his mentor General John Morgan’s interview with Forrest: “Morgan wanted particularly to know about his fight at Murfreesboro, where Forrest had accomplished a marked success, capturing the garrison and stores and carrying off everything, although the surrounding country was filled with Federal forces. Morgan asked how it was done. ‘Oh,’ said Forrest, ‘I just took the short cut and got there first with the most men’” (Wyeth, p. 568-9).

The opposing side got off the first shots in Forrest’s first gunfight in 1845, and it cost his beloved uncle his life. He appears to have taken the lesson to heart and adopted it in the military strategy that made him famous. In line with this …

Intimidation can prevent bloodshed, but it also has to be explainable. An older and wiser Forrest might have simply shot James Dyson instead of taking him at gunpoint in his second, early civilian encounter. As a battlefield general, Forrest’s habit of offering written terms of surrender to the enemy — stating in essence, if you give up you’ll be safe and treated with respect, but if you don’t, we’ll put you all to the sword — allowed his forces to capture more enemy personnel than they killed in many of his battles. However, the same terminology came back to haunt him after the Battle of Fort Pillow, when his men apparently did kill some helplessly surrendered troops and he spent the rest of his life accused of being a racist butcher. His explanation did, however, keep him from having to go to trial.

Be a good wizard, not a bad one. Even his enemies called Nathan Bedford Forrest a “wizard of the saddle,” but his becoming the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan would be remembered forever after his death, even though he spent the last eight years of his life disavowing the sheetheads. He’s seen today as a quintessential racist, even though the “Freedmen’s Bureau” of the post-War time chastised him for allowing blacks who worked for him after the Civil War to own and carry firearms. (See any hypocrisy there?)

The bottom line? Great men tend to have great strengths and great flaws. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s life experience tells us we should all learn from the former and assiduously avoid the latter.

Partial Bibliography:A Battle From the Start: the Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest by Brian Steel Wills, 1991, Harper-Collins, NYC; That Devil Forrest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest by John Allan Wyeth, first published 1899, current edition Louisiana State University Press, 1989; Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography by Jack Hurst, Alfred A. Knopf Publishers, NYC, 1993.

[Note: Correct purchase info for “Self-Defense Laws For All 50 States” (Ayoob Files, May/June 2016) should be: www.amazon.com.]