"It’s a Blow- Back Auto”

Yeah, But What Does That Mean?

Esteemed and worthy editor Roy forwarded a message from Handgunner reader Mike Quill: “There are terms I run across which make me feel like a third grader in a post-doctoral physics class… perhaps you could persuade or induce one of your technical geniuses to do an article explaining what are the differences between various firearms terms?”

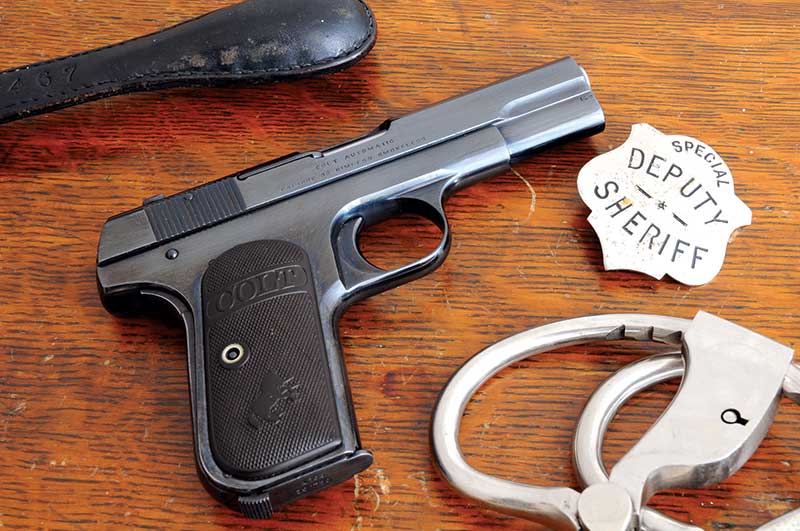

While not a genius, Mike (just ask His Editorship), I’ll give it a shot, as it were. One of your questions concerned the difference between blowback and locked-breech designs. With a blowback action, the slide (or bolt, as in the Ruger Mark series of .22’s) is not locked to the barrel. The face of the slide is held against the chamber end of the barrel by the compression of the recoil spring.

When the cartridge is fired, expanding gases build pressure in all directions, but is contained in the chamber. Pressure on the base of the bullet begins accelerating it down the bore. Pressure on the interior of the case head pushes it against the face of the slide, which accelerates in the opposite direction. Since the bullet is much lighter it accelerates much more quickly than the slide. In addition, as the slide moves back it has to compress the recoil spring. The net effect? As the bullet exits the barrel, the slide has only begun to move.

Once the bullet exits the muzzle, gas pressure in the bore and chamber is released. The momentum imparted to the slide keeps it moving back. There is enough residual gas pressure to extract and eject the fired case from the chamber.

No Extractor?

Most blowback semiautos do have an extractor, its purpose is to remove unfired cartridges from the chamber for unloading. When cartridges are fired, there’s enough residual pressure that fired cases extract and eject without needing a mechanical extractor. Beretta has made blowback semiautos with no extractor at all; the barrel is hinged near the muzzle so the chamber end can be lifted to remove an unfired cartridge.

The basic blowback design is simple, and compared to more complex designs relatively easy and inexpensive to manufacture. Extraction and ejection of fired cases is brisk and reliable. The relatively heavy slide and strong recoil spring impart a lot of momentum to the slide as it moves forward, making for reliable feeding of the next cartridge.

Many blowback designs have the barrel fixed to the frame, a feature that enhances accuracy. Some of the small pocket automatics such as the Walther PPK are surprisingly accurate, within the limitations of their short sight radius and often heavy trigger pulls. Blowback .22 semiauto target pistols are superbly accurate.

On the negative side, with centerfire blowbacks the slide is moving fast when the frame stops its full rearward movement, accentuating recoil. Most designs have a fairly strong recoil spring, making it more difficult to manually retract the slide for loading or unloading. Although often touted for those with smaller, weaker hands and arms, the blowback .380’s aren’t really always the best choice.

Locked-Breech

The trend with currently manufactured .380’s has been to locked-breech designs. With these, slide velocity is lower and felt recoil is less. Recoil springs don’t need to be so strong either, making the slide easier to retract. A locked-breech .380 is much more pleasant to shoot compared to my blowback autos.

The main objection to blowback design is (with some exceptions) it’s limited to low pressure, low power cartridges such as .22 rimfire and .25, .32 and .380 ACP. Blowback pistols in 9mm and .45 ACP have been — and are — made and used successfully, however. Sometimes these were made as part of a war effort since the relatively simple design can be produced quickly and at moderate cost. The issues of felt recoil and heavy recoil springs are even greater than with lower-powered cartridges. These days the blowback design is seen most often with .22 rimfire pistols and rifles, but the popular Hi-Point line of semi-autos are also blow-back, in 9mm, .40 and .45 ACP.

Blowback designs proved semi-auto pistols worked, and handgunners liked them. But as always, handgunners wanted more power, but without a lot of added weight and recoil. And human ingenuity being what it is, a series of brilliant designers came up with not one solution, but several. Which is another story!