Lessons From the

Battle of Adobe Walls

Situation: You are surrounded by a huge enemy force that wants to kill you…but you have cover, guns, ammo and shooters both skilled and highly motivated.

Lessons: The ensconced defender has some significant advantages. Firepower counts, especially when outnumbered. The ability to hit under pressure cannot be overestimated.

In October of 2023, Hamas terrorists attacked Israeli communities with machine guns and grenades. The communities that were not armed were savaged, with helpless women, children and men slaughtered or kidnapped. However, early reports indicated that at more than one kibbutz, where the residents were armed, the residents fought off the attackers and killed many of them with few or no casualties on their own side.

It was a repeat of a dynamic we have seen in the past and will undoubtedly see again in the future. A classic example of this principle was recorded in the United States in the Old West.

In June of 1874, in what is now Hutchinson County, Texas, some 29 people were besieged by a force of native American warriors generally estimated to number 700. The siege lasted for days.

Famous people would be involved. The chief of the Comanche attackers was already well-known. Among the buffalo hunters who stood against them were a young man destined for future fame and another who would earn heroic notoriety right there.

When it was over, only four of the defenders had died, and half of those had been lost in the opening part of the fight when caught unaware. Estimates of the dead on the attacking side ran between 100 and 150.

Twenty-five-to-one odds to start, favoring the attackers. If we split the difference between the postulate of 100–150 dead Indians and call it 125, that’s a 32.25-to-1 death rate favoring the defending side.

There are lessons to learn from a conflict that ends with figures like that.

Prelude

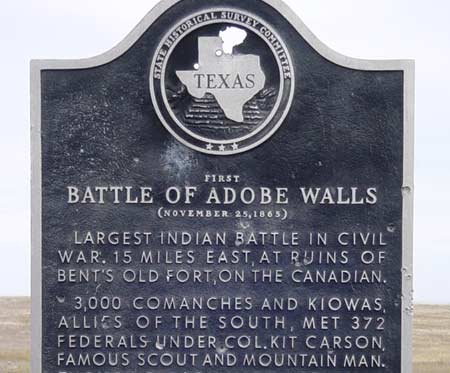

Adobe Walls. When many people speak of the conflict there, they don’t realize they’re talking about the Second Battle of that name.

A famous man of his time was present at the First Battle of Adobe Walls. His name was Kit Carson. The celebrated Indian fighter was leading a task force. In Kit Carson at Adobe Walls, Clay Coppedge says of Carson, “ … he was sent to Texas in 1864 to find and punish, with extreme prejudice, the Comanche and Kiowa who were making life miserable and death a real possibility for wagon trains on the Santa Fe Trail. Carson followed the Canadian River onto the Llano Estacado, or Staked Plains, where no one, not even the Texas Rangers, had ever ventured in pursuit of Comanches, the fear being that they might actually find them.”

Carson and his men had some initial success, but it didn’t last long. They would soon be grateful they had brought along two howitzers. Their opponents gathered reinforcements rapidly. Coppedge writes, “The subsequent Comanche attack was relentless and, Carson noticed, aided in no small part by a steady stream of reinforcements riding into the fray from a much larger Comanche village that he and his scouts could now see clearly. By afternoon, some 3,000 warriors had joined the battle.”

Historian Coppedge adds, “This was similar to the blunder that George Armstrong Custer would later make at the Little Big Horn, the difference being that when Carson’s scouts told him he should leave that place or die there, he listened. The troops retreated, but the Comanches now outnumbered Carson and his men by 10-1. Carson again unleashed the howitzers, and that weapon alone allowed Carson and his soldiers to make good their escape under cover of darkness.”

The Second Battle Begins

The scene was a trading post in the Great Plains. Adobe Walls consisted of a couple of stores and a saloon. The 29 people who would face the assaults included one woman, a storekeeper’s wife and a few people who staffed the place. The remainder were buffalo hunters: Men who lived by their skill with their heavy caliber rifles.

The approaching horde of Comanches was led by Quanah Parker, the son of an Indian chief and a kidnapped white mother who had adapted to tribal life. Among the hunters was a young man named Bat Masterson, who, many years later, would become one of the most famous American lawmen of all time. There, too, was one Billy Dixon, generally accepted as the best shot among all the marksmen present on the defending side. Before the fight was over, he would perform a shot that would live in song and story thereafter.

Early on the first morning of what would be a five-day siege, stealthy Comanches crept up on two brothers who made the mistake of sleeping in their wagon outside the stockade. They killed and scalped both men and their dog, a big Newfoundland. The attack had begun.

Inside Adobe Walls, a roof support beam had broken with a loud crack, and the awakened hunters hastened to fix it. It is believed this is why they were awake and ready to respond instantly when the attack came.

Most of the hunters wisely barricaded and returned fire from behind cover. One did not. Moving between buildings, he took a Comanche’s bullet through the chest and became the third defender to die.

But the rest of the defenders held their cover and focused on careful shooting. They faced an intimidating foe. Billy Dixon later wrote, “There was never a more splendidly barbaric sight. In after years, I was glad that I had seen it. Hundreds of warriors, the flower of the fighting men of the southwestern Plains tribes, mounted upon their finest horses, armed with guns and lances, and carrying heavy shields of thick buffalo hide, were coming like the wind. Over all was splashed the rich colors of red, vermillion and ochre on the bodies of the men, on the bodies of the running horses. Scalps dangled from bridles, gorgeous war-bonnets fluttered their plumes, bright feathers dangled from the tails and manes of the horses, and the bronzed, half-naked bodies of the riders glittered with ornaments of silver and brass. Behind this headlong charging host stretched the Plains, on whose horizon the rising sun was lifting its morning fires. The warriors seemed to emerge from this glowing background.”

“Excitement gave place to cool resolution and unerring precision of marksmanship,” according to researcher Edward Campbell Little. Little cites the following quote from Bat Masterson, who was 20 years old at the time: “Directly, I saw Mr. Indian backing my way, getting out of range of fire from Bob Wright’s store. I commenced getting a bead on him. As he backed an inch or two more, I let fly, and Mr. Indian bounded in the air about three feet, dropped his rifle and fell dead. I turned around to Shepherd and said, ‘Shep, I got him the first crack.’”

Most of the heavy combat occurred in the first two days of the battle. Quanah Parker was among the wounded on the Comanche side.

Each time the mounted warriors charged, they were met with deadly, accurate fire. The hunters made a point of picking off the obvious leaders, which is how Quanah Parker got wounded. By the third day, the gunfire was tapering off, and the Comanches were keeping their distance. Meanwhile, a couple of hunters had escaped Adobe Walls and ridden for help.

The decisive turning point came on the third day. Seeing 15 or 20 of the Indians gathered nearly a mile away, Billy Dixon ventured a shot … and one of the braves toppled from the saddle.

The effect on the raiders was understandably profound. The charges ceased. By the end of that third day, reinforcements had arrived at Adobe Walls. Day five saw the native Americans retire completely from the battlefield.

Only when the battle was over was the fourth of the defenders killed — by a shot to the head from his own weapon when he fumbled with it while descending a ladder.

So, Who Won?

Most of us see the outcome as a decisive victory for the defenders. Still, different historians have different takes on who won and lost. In Quanah Parker and the Battle of Adobe Walls, author Richard Hummell opined, “The outgunned Comanches were eventually forced to give up the fight, and this battle had a profound impact on Quanah as he made future decisions to ensure the survival of his people.”

Historian H.W. Brands had another view of who could be perceived to have won what in the Second Battle of Adobe Walls. He wrote, “Perhaps the Indians decided they didn’t want to tangle any longer with hunters who could shoot like Billy Dixon. Perhaps they had already concluded they’d made clear the southern plains would not be safe for the buffalo hunters. This was the purpose of the attack. Quanah Parker and the other Indians didn’t have to kill all the hunters; they merely had to disrupt the hide trade before the hunters killed all the buffalo. Dixon and the other hunters were in the business to make money, not to become heroes. Simply by raising the cost of securing and delivering hides — by requiring guards around their camps, compelling the pack trains carting the hides to Dodge City to enlist armed escorts — Quanah might make the hide trade unprofitable and thereby force the hunters to abandon it.”

The Weapons

In The Second Battle of Adobe Walls: Quanah Parker and Isa-tai Against Billy Dixon and the Buffalo Hunters by Richard Duree, we find the following: “ … in the store were cases of Sharps rifles — ‘Big Fifties,’ that could kill a 2,000-lb. bison at a thousand yards with their 600-grain lead bullets. There were cases of over 11,000 rounds of ammunition. Every man was also armed with sidearms and many had Winchester repeating rifles. Archaeological excavations a century later revealed several Colts with Richards conversions, some S&W Americans and even a brand-new Colt SAA, in addition to several rifles in .50-70, .50-90 and at least one .45-70, which were also new at the time. The post was not only well fortified, it was well armed.”

On the other side, the Comanches had rifles and revolvers, too. Something like 50 of their bullets would later be found lodged in the namesake adobe walls.

The Last Campaign: Sherman, Geronimo and the War for America by H.W. Brands contains an excellent account of the battle, what led up to it, and how it affected the course of subsequent events. Brands writes, “Dixon had lost his Sharps .50. He said, ‘The only gun at the Walls that was not in use was a new .44 Sharp’s (sic), which was next best to a .50. This gun had been spoken for by a hunter who was still out in camp; he was to pay $80 for it, buying it from Langton who was in charge of Rath & Wright’s store. Langton told me that if necessary, he would let me have the gun, as he had ordered a case of guns and was expecting them to arrive any day on the freight train from Dodge City, and he probably would have them in stock before the owner of the gun came in from the buffalo range.’ … Dixon took the gun and purchased a case of ammunition.”

Brands offers cogent comments from Dixon himself to show the cool state of mind and focus on purpose that characterized him and his comrades during the fight. Brands quotes Dixon, “We were keenly aware the only thing to do was to sell our lives as dearly as possible … We fired deliberately, taking good aim, and were picking off an Indian at almost every round.”

Again from Brands, “‘The Indians would ride toward us at headlong speed with lances uplifted and poised, undoubtedly bent upon spearing us,’ Dixon said. ‘Such moments made a man brace himself and grip his gun.’ Each time, though, Dixon or one of the others would put a bullet into the leader of the charge, and the others would peel away. The charges gradually grew less frequent.”

The Famous Dixon Shot

Alongside Quanah Parker at Adobe Walls was the medicine man Isa-tai, who had assured the braves his medicine would make the white man’s bullets impotent. It would be interesting to know what the survivors had to say about that after their comrades’ corpses had been counted. That final shot by Billy Dixon had shown the warriors just who had the strongest “medicine.”

Most historians put the distance at some 1,500 yards for that spectacular shot. Who was the man who directed that fateful bullet? According to historian Brands, “Dixon displayed a knack with a rifle and was promoted to chief provisioner of the camp. ‘I always attributed my skill with the rifle to my natural love for the sport, to steady nerves, and to constant, unremitting practice,’ he said. ‘Where other men found pleasure in cards, horse racing and other similar amusements, I was happiest when ranging the open country with my gun on my shoulder and my dog at my heels, far out among the wild birds and the wild animals.’”

Here, Richard Duree envisioned it from the Comanche side, “The final blow was to come as a small band of warriors rode out to take a hard look at the post, hopefully to envision a new course of action. As they watched, a puff of smoke burst from one of the store windows. Curious, they watched. Again, another puff. And a third. As they watched this curious thing, a loud thud was heard, and one of the warriors suddenly threw up his arms and fell backward from his horse — dead with a .50 caliber bullet from Billy Dixon’s borrowed .50-90 Sharps buffalo gun, perhaps the most famous shot fired in the Old West.”

And here is an addendum to Duree’s work, which mentions American Handgunner’s own Mike Venturino: “In tests conducted by the U.S. Army using highly sophisticated radar equipment, the .50-90 Sharps fired a 675-grain bullet at a 35-degree angle, with a muzzle velocity of 1,216 fps, a distance of 3,600 yards. An angle of 5.5 degrees achieved a ‘Billy Dixon shot’ of just over 1,500 yards. A 458-grain bullet, with a muzzle velocity of 1,416 fps and 35-degree elevation, traveled 2,585 yards, indicating the effect of bullet weight. The tests were viewed and recorded by no less a personage than Mike ‘Duke’ Venturino, armaments tester and author.”

Dixon himself modestly attributed the feat to luck. He called it a “scratch shot.” That was probably too modest. The buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls had earlier made a habit of betting each other for the best shot at an outcropping some 1,500 yards away … pretty much a dress rehearsal for the shot that made Billy Dixon famous.

That fame would grow. A few months later, at another Indian fight, the Battle of Buffalo Wallow, Dixon acquitted himself with such courage and skill that he was awarded a Medal of Honor.

Lessons

The ensconced defender has a very strong advantage. Behind cover, the defender is a very difficult target, particularly for opponents bouncing on horseback. The Comanches had to come at the buffalo hunters, totally exposed and terribly vulnerable.

Shooting skill is important. As with the David and Goliath model, the ability to deliver death from a distance was crucial here. These men made their living killing large, potentially dangerous animals from a distance, “one shot/one kill.” They had long-range weapons and the opportunity to brace them over or against their cover for additional solidity of aim. They employed those weapons and skill to great advantage.

Use the optimum force multiplier against the given threat. Those magnificent warriors riding across the plain, as Dixon described, coming straight at them so they didn’t even need to lead their targets, were easy meat for the long-range rifles of the buffalo hunters.

Let’s go back to that First Battle of Adobe Walls. Said historian Coppedge, “One advantage that Carson had on this expedition was a pair of howitzers, large caliber cannons that worked essentially like a huge sawed-off shotgun, spraying hundreds of .69 caliber cannon balls with each shot. Howitzers could turn a large crowd of warriors into a small gathering of survivors in a matter of minutes. The Comanche would call it ‘the gun that shoots twice.’” Coppedge added, “The U.S. military claimed the battle as a rousing victory, but Carson didn’t quite agree. Without the howitzers, he said, ‘few would have been left to tell the tale.’ This was to be the last battle Kit Carson would ever fight. Despite what the official report said, Carson would say, ‘The Indians whipped me in this fight.’ As usual, he was right.”

Don’t sacrifice cover. All three of the hunters killed by the raiders would have lived had they taken cover. The brothers, who were the first to die, apparently thought the danger was sufficiently minimal to sleep outside the compound, and it cost them their lives. The man who exposed himself to go to another spot, leaving cover, paid for it with his life.

The Second Battle of Adobe Walls took place a century and a half ago. As recent events in Israel prove, the lessons from that fight are timeless. The clothing, the weapons, and the conveyances that bring the combatants to the fight may change, but the essential dynamics of lethal human violence remain constant through the ages.