Specialization Is For Insects

Does That Apply to Gunsmiths Too?

Actually, the quote is: “A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.” Robert Heinlein

What he says about being a jack-of-all trades is important, and not just in everyday lives — although it’s really important there too. Like many (most?) of you, I was a certified gun crank from my first taste of sentiency. My fingers naturally formed a make-believe pistol as I did battle with my classmates at recess (remember when we could do that?). Sticks became rifles, and soon a borrowed coping saw helped me turn planks into imaginary machine guns and mortars. Once I got my first “real” gun, a Remington Model 514 .22, I realized this was the real deal and acted accordingly, thanks to Dad’s instruction.

But right off, I kept thinking, “Hey, this thing needs one of those sling-things, and I wonder what else I could do to make it better?” Gunsmithing was truly in my genes from the beginning (remember that coping saw?) and I vividly remember amassing a small toolbox of my “gunsmith” tools when I was about 12 or so. Sorta’ broken screwdrivers, pliers, a small hammer someone gave me … you know the story. Each was cleaned, treasured and put to good use fussing and twisting screws on that Remington. That’s how I started to learn about guns and how they work.

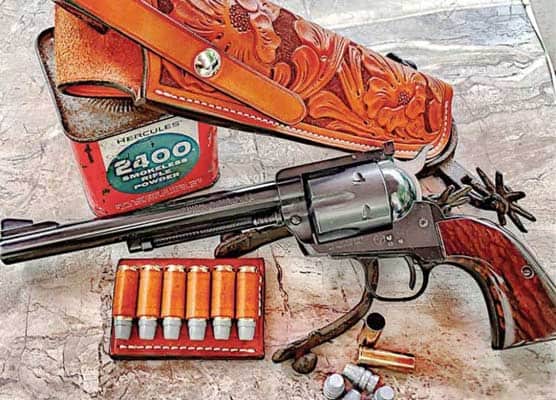

Time passed and the affliction grew, along with the toolbox. Dremels followed, and when a Unimat lathe arrived in 1975, there wasn’t an unthreaded rod lurking anywhere safe from my administrations. S&W revolvers were taken down, worked over (messed-up), broken, fixed, adjusted, tweaked, broken again, and the college of self-learning — and hard knocks — continued for decades. By the middle 1980s, I was getting fairly good, and simply because I didn’t have the luxury of a lot of money, I worked on whatever I could lay my hands on.

Word gets around fast in a gun community and soon people were finding me and asking me things like, “Hey, um, I heard you could fix a gun? I got this old .22, think you could fix it?” And what is it about old top-break revolvers that makes people think once the flat-springs are broken, grips are cracked, screws are missing and worse — it’s a good idea to get it fixed? To each it’s a treasure (“Grandpa’s old gun, I’d like to get it working if you can.”) so I couldn’t say no. But I learned a lot, constantly, and even today if you hand me a Trapdoor Springfield, or an early Iver Johnson .32, or a Mauser Broomhandle or a Marlin Model 60 or a malfunctioning Browning Auto 5 shotgun (usually they recoil spring bushings are put back in the wrong order) — I can generally get things to work again.

Nowadays I have a lathe and a milling machine and two rolling toolboxes of genuwhine gunsmithing tools of all kinds. And while we can joke hobby gunsmiths are a “real” gunsmith’s best friend (I’ve put my share of “bag-o-guns” back together for people), the reality is the competent general gunsmith’s days seem to be numbered. Like too many things today (think: doctors), we have specialists in 1911s, or Glocks, or Winchester lever actions, or sporting clays shotguns, or Colt SAA revolvers — and the list goes on. But it’s getting increasingly difficult to find someone who will smile as you hand him your Remington Model 742 or Colt Python or, dare I say, Marlin Model 60 .22, as you tell him “Um, it’s not running right, I think something’s wrong.” Plus, most people don’t want to pay what it’s really worth for a gunsmith’s time, especially when the gun in question is only worth $100. It’s a vicious circle, and people in need of basic gunsmithing are usually the losers.

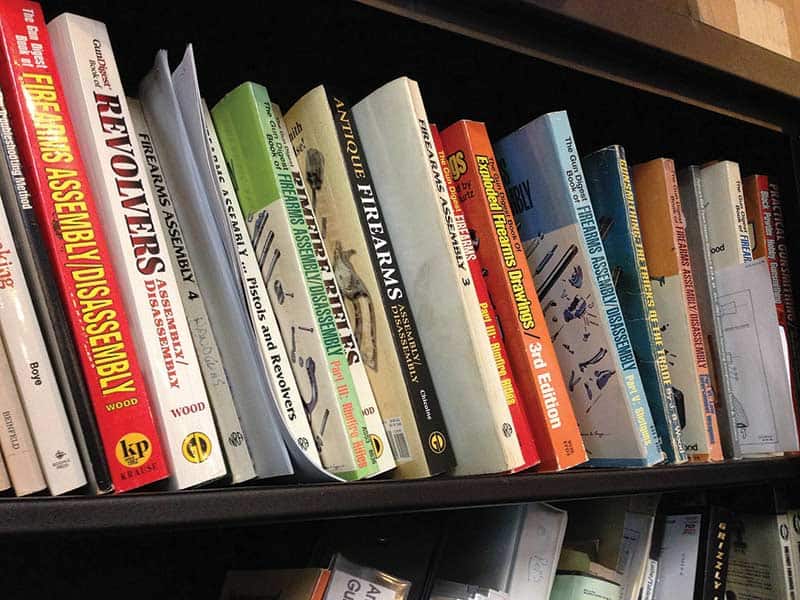

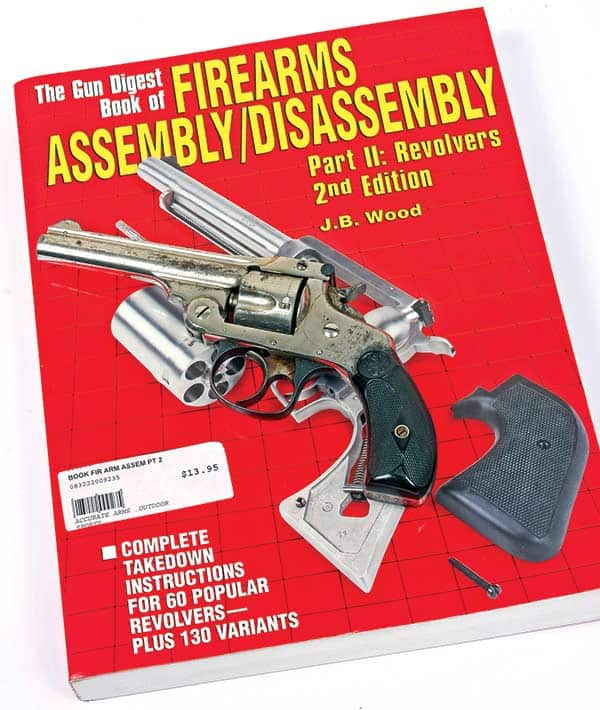

It’s always been a bit of a detective mystery to me when I’m handed a broken gun. “Hmm … what’s afoot? I’ve never seen one of these before. I’d better get my J.B. Wood disassembly books down to see if I can find it there. I wonder if Numrich will have any parts needed, or will I need to make them?” These days I only work on my own guns, and as a favor for my friends now and again I’ll help them out. I still get a kick out of the big smile as a buddy tries out a gun I’ve fixed for him. “Hey, this is great, it runs like a champ again. Thanks so much!” Who needs money?

I’m the first to admire the work of today’s custom ‘smiths and the marvelous talent they have. You only have to look in our pages to see it. But I wonder what do people with broken .22s, or old Walther .380s that won’t feed do? It’s getting tough for me to find a gunsmith to help them out. I’m not sure what to do, but can say one thing for sure. If you’re inclined to learn, get started now. Buy some books, get a Brownells catalog, read everything you can lay your hands on about guns and find some old broken .22s — and go to work.

Trust me, there are far worse ways to spend evenings in the garage. The first time you hear the sharp crack of a .22 from a gun that had been silent for years will remain etched in your mind. “I fixed that,” you’ll say to yourself quietly. And if you’re lucky, it will spark a need to know more and to learn what’s next. Pretty soon you’ll be hearing, “Hey, I hear you could fix this old top-break .38 S&W my grandpa had. Mind taking a look at it?”

If you’re serious about this — and I hope you are — start collecting the Assembly/Disassembly books by J.B. Wood (check www.amazon.com), go to www.brownells.com and start to learn about tools, and think of investing in some DVDs on gunsmithing from the likes of the AGI School of Gunsmithing (www.americangunsmith.com). If you’re lucky enough to know someone who is a hobby gunsmith or tinkerer, get them to teach you what they know.