Striker Vs. Hammer Which Wins?

We really like sharing thoughts and conversations with Handgunner readers. Editor Roy suggested a column in response to this comment he got: “I’ve shot enough to know the difference between striker-fired pistols and hammer-fired, but what I don’t know are the pros and cons of selecting one type over another — John Ashjian.”

Interesting question, John, though I’m not sure there’s a definitive answer. Both designs have their attributes, and depending on intended use can be positive or negative. As a further complication there are variations of both basic designs. My Beretta 92D for example, has a hammer but no hammer spur and cannot be cocked.

In some striker-fired models, like the Glock, the mainspring is partially compressed when a cartridge is chambered. The trigger has to then move far enough to fully compress it before releasing the sear to fire. With others, like the Springfield XD series, the mainspring is fully compressed and requires only a short trigger movement to fire.

A hammer/sear design can be tuned and fitted to provide a very crisp, short, light trigger break. Examples are a cocked S&W revolver, S&W 41 target .22, or a tuned 1911 trigger. So is this an advantage or a disadvantage?

Most competition shooters and handgun hunters consider a crisp, short, light pull an advantage. For a defensive handgun likely to be used under high stress and the resulting loss of fine motor skills, it might well be a disadvantage.

With a design such as the 1911, if a trigger pull results in a “click,” possibly due to a light primer strike, the hammer can be thumb-cocked for a second try. Most current instructors feel this is a waste of time. Instead they teach a broad-spectrum drill. If the gun clicks, smack the magazine to ensure it’s seated and locked, rack the slide and fire.

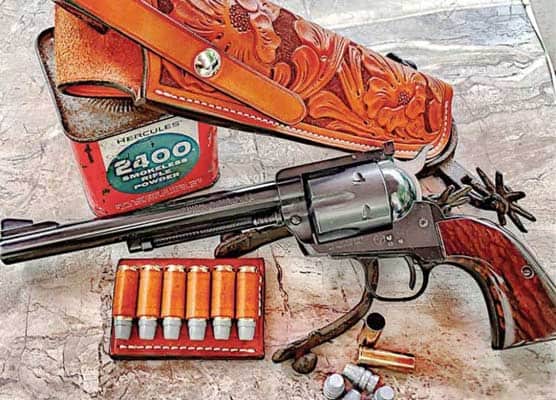

In a hammer design, the weight of the hammer provides considerable momentum to drive the firing pin, striking the primer a brisk blow, enhancing ignition. With some holster designs a safety strap can be snapped between the hammer and the frame, providing additional security.

If you want to store the unloaded pistol with the mainspring relaxed, the hammer spur provides the option of carefully lowering the hammer with the thumb. The hammer also provides immediate visual or tactile confirmation as to whether it’s cocked (though not, of course, whether there’s a cartridge in the chamber).

Some designs have several carry options: mag loaded/chamber empty, hammer down/loaded chamber, DA first shot, cocked and locked, etc.

There’s a risk the hammer spur can snag on clothes, especially if the handgun is being carried concealed. And, with some older designs, a sharp blow on an exposed hammer, such as from the gun being dropped, can cause it to fire. But training can help overcome this sort of thing.

Striker-Fired

There’s no hammer to snag on clothes, or to be struck should the gun be dropped. Trigger pull is consistent for every shot, although it may not be as crisp as many SA triggers. The manual of arms is simple: Insert loaded magazine, chamber a round, holster pistol and go about your business. Some do have the option of a manual safety you can engage after loading.

Since the striker is light compared to a hammer, the mainspring is usually stronger to help provide the energy for positive ignition. Many (not all) striker-fired pistols have no “second strike” option. A “click” means running the slide again to cock the striker. Many (again, not all) require the pistol to be dry-fired on an empty chamber before disassembly, or if the shooter wants to relax the mainspring before storing the pistol.

If I look at my most-used handguns the majority are hammer fired, mainly because I used 1911 pattern pistols in competition for years, and I also like revolvers, too. But, there are several striker-fired favorites as well. I must say, I really don’t worry about the issue one way or another.