The Long Vs. The Short Of It

In a letter to Handgunner reader Jens Jensen commented, “Roy … I read the book he (John Taffin) suggested, The Secrets of Double Action Shooting by Bob Nichols. Nichols kept raving about the prewar long action vs. short action S&W revolvers.” Jens went on to suggest he’d be interested in an explanation of the difference between the two. Here goes, Jens.

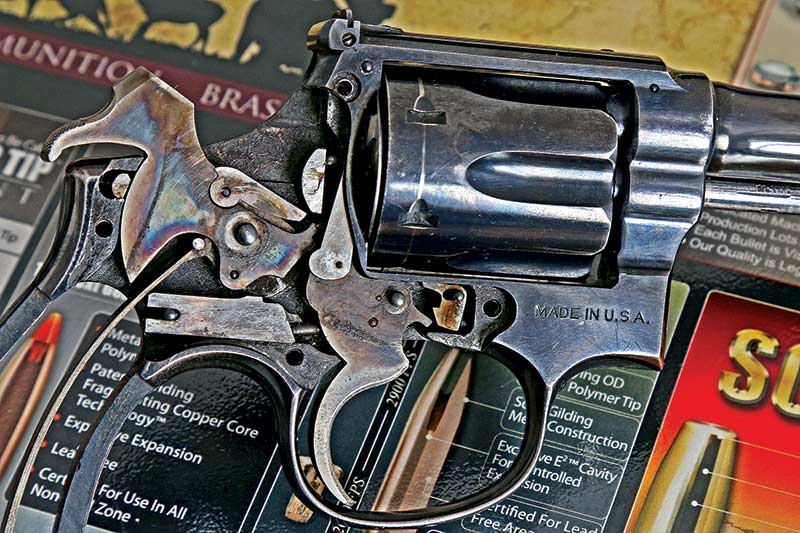

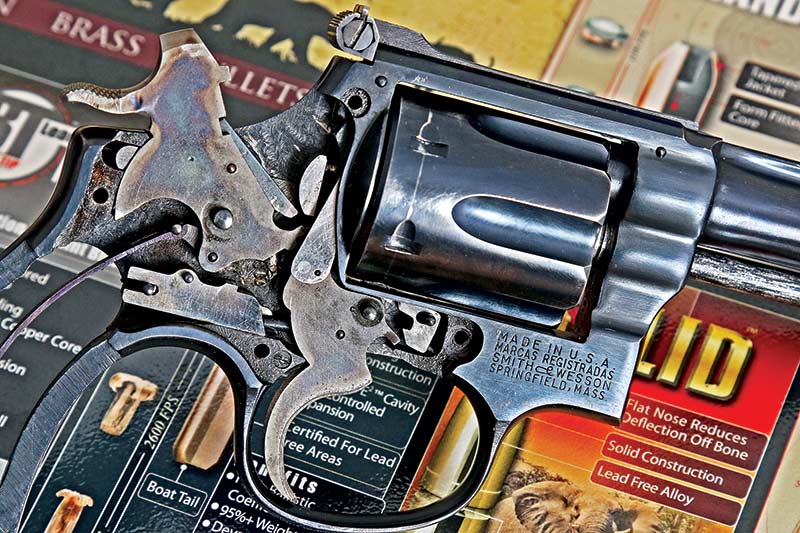

Short vs. long action refers to the arc swung by the hammer when cocked and fired. The long action hammer moves slightly farther back when cocked, and swings through a slightly larger arc when fired. Seems hardly enough to get excited over but in the early post-war era the topic generated many a heated argument.

S&W began contemplating the redesign in the 1930s. Bullseye shooting was virtually the only competitive handgun sport. Shooters competed in three categories: .22 rimfire, “Any Centerfire” which in practice meant .38 Special, and .45 ACP. While there were some quality .22 autos at the time (e.g. Colt Woodsman and High Standard) they weren’t very popular with target shooters.

The “Any Centerfire” category was dominated by S&W K-Frame and Colt Official Police frame .38 Special revolvers. I wasn’t there at the time but I knew someone who was, the late Col. Charles Askins Jr. In The Pistol Shooter’s Book (1953) Askins wrote, “The more popular target sixgun is the Colt … for many years the S&W company produced a revolver too light and poorly balanced. Too, the model was hard to cock when shooting rapid fire … it was difficult for many shooters to cock the weapon smoothly and quickly.”

If your centerfire revolver is a Colt it makes sense to use a matching Colt in .22 LR. The Colt Officer’s Target model .22 was very popular. I own an example made in 1937 and it is indeed a superb revolver. S&W was rightfully proud of the quality and accuracy of the new K-22 introduced in 1930–’31. Often referred to as the “Outdoorsman” (take that, Colt Woodsman!), it sold quite well despite the Depression, with 17,117 produced from January 30, 1931 to December 28, 1939 (from History of Smith & Wesson by Roy G. Jinks).

S&W Pushes Back

Having archrival Colt dominate competition no doubt irritated S&W and they began redesigning the K-22 to answer shooter concerns. January 25, 1940 they released the K-22 Masterpiece with a newly designed click adjustable rear sight and a new short action intended to improve lock time, make cocking easier, and allow cocking without the shooter having to alter his grip. Then a little matter called World War II intervened. According to Jinks only 1,067 of the revised model were made. Production ended December 12, 1940 as S&W diverted all its efforts to military production.

After the war S&W reintroduced the short-action K-22 with a heavier ribbed barrel, with sales beginning December 13, 1946, followed by the K-32 and K-38. In 1948 the Military & Police transitioned to the short action, followed by the N-Frame revolvers around 1949.

The merits of long vs. short action for DA shooting were hotly debated for years — and still are — 70 years after the last long action S&W was made. LA enthusiasts argue the longer fall of the LA hammer provides reliable ignition with a lighter mainspring. Another LA claim is the mainspring is compressed over a longer rotational arc. As a result the LA can provide a lighter and smoother DA pull.

After shooting both styles fairly extensively I can’t say I find either system notably better. Trigger movement and especially trigger reset are key factors in fast, accurate DA shooting. Trigger travel is the same with either design. It’s my belief a light pull is of no advantage when it comes with a sluggish trigger reset.

Great Care Wins Out

A strong argument for LA superiority is observation. S&W revolvers made in the 1930s often had splendid DA pulls out of the box. The best examples, such as the .357 Registered Magnums, are considered by many the best ever made. The LA design seems to have gotten much of the credit.

I think the brutal economics of the Great Depression were the main factor. Firearms demand was low; there was no incentive to cut corners and speed production, quite the opposite. Workers wanted to keep their jobs; managers didn’t want to lose their highly skilled and trained employees. Workers could take time, for example, to pick through hammers and triggers to find an exceptional match. Great care could be lavished on fit and finish.

I’ve noticed the same dynamic with other makers such as Colt, Savage and Winchester — virtually custom-made, hand-fitted quality at production prices. It was really just a rare moment in time, a fluke of circumstance. I suppose it is human nature to forget the misery and hardship of the Depression and remember the few bright spots.