My Route To the Ruger Redhawk

My first handgun was a Ruger Service Six .38 Special, which I was issued as a rookie cop in 1985. This started my fascination with Ruger firearms. Our department armorer told us all the advantages of the investment cast gun, mainly that it is stronger than needed and robustly strong. He told us we’d never wear them out, and the more we shot them, the smoother the action would become.

He was right! After almost 10,000 rounds, the double action was buttery smooth. I learned a lot from that fixed-sighted gun. My gun specifically shot 2 inches to the right at 2 yards. When I brought this up to the same armorer, he grabbed my gun, tapped up a new target and sent it down range to the 25-yard line. He then shot a full cylinder worth and brought the target back. A small 2” group could be seen 2” to the right. He simply said, “aim 2 inches left.” And walked away.

It was here I developed my shooting philosophy, which was simple. Rather than complain about the gun, adjust yourself around the gun and continue. I did what he said, finishing second in my class for shooting.

Redhawk’s Away

After being on the department for a few years, I started getting interested in bigger guns. Don’t we all? Loving my Ruger Service Six, I was drawn to Ruger’s Redhawk, which was released in 1979. Looking like a beefed-up version of my Service Six and chambered in the .44 Magnum, I thought I had a dandy of an outdoorsman’s revolver. And I did! I went with the stainless 7.5” barrel version. At that time, the Redhawk had yet to be chambered in .45 Colt.

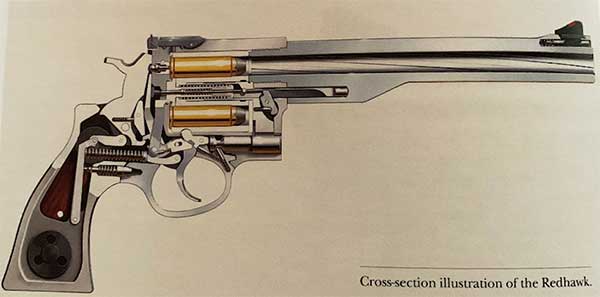

The frame is basically the same as the Service Six — being of solid one-piece design, with no side-plate — but the innards are different. Breaking down is still easy, as well as reassembly, which is good, especially for me.

By now, I was handloading and casting bullets, so ordered the dies and molds necessary to load ammunition for it. I really enjoyed shooting the gun and appreciated the sight radius the 7.5” barrel offered. It made hits much easier than my 4” Service Six at longer distances. Over time, several more Redhawks followed me home in different barrel lengths and chamberings, namely .45 Colt and .41 Magnum. I’ve yet to capture the elusive .357 Magnum Redhawk. But you never know.

Redhawk Advantage

I later learned that Redhawks have a major advantage over other double actions of different makes, mainly being the Redhawk cylinder is longer and larger in diameter. These larger dimensions allow handloaders to seat bullets further out than standard overall cartridge length (COL). Doing so increases powder capacity, allowing more powder to be added, while staying within the same pressures as other loads, but producing higher velocities. Molds from Lee Precision, Lead Bullet Technology (LBT) and MP Molds address this with some of their bullet designs having two or more crimp grooves.

Driving 300-grain bullets over 1,500 fps is possible when the .44 Magnum Redhawk is loaded this way. Spent brass extracts easily with the push of the ejector rod with a single finger. Redhawks in .45 Colt can drive 320-grain bullets over 1,350 fps when loaded the same way.

Ejector Erector

Bill Ruger also thought up the ingenious ejector of the Redhawk, where the rod is in the center of the cylinder but not in center of the axis of the frame. The ejector rod is offset and doesn’t rotate axially with the cylinder. This allowed more meat in the frame in this area, increasing thickness 100% and doubling the frame’s strength.

Redhawk Rectification

Some Redhawks have a bad reputation for light primer strikes, which can cause fail-to-fire (FTF) scenarios. If the mainspring hasn’t been monkeyed with, the solution is easy to remedy. Guns with transfer bars (TB) need to have a perfect meshing of parts, allowing proper ignition. As the trigger is pulled, the TB raises, covering the frame-mounted firing pin.

When the hammer falls, the hammer notch is filled with the TB and the energy from the hammer blow is transferred through the TB to the firing pin. It’s critical the TB and hammer notch are sized properly. If not, misfires occur. When the top of the hammer strikes the frame prematurely, it lessens energy transfer to the TB.

The solution is simple. Simply removing enough of the hammer face (around .20 inch) where the hammer contacts the frame allows the full force of the blow to be transferred to the TB for complete ignition of the primer. Not all Redhawks have this problem, but if yours does, it’s an easy fix.

Redhawk Reverie

I love my Redhawks and enjoy shooting them very much. I enjoy shooting double action with them, too! There is no better trigger exercise in the world than shooting double action revolvers. Once mastered, this skill transfers to all guns. While single actions still get the nod as one of my favorite handguns, the double actions come a close second, especially when they are robust Ruger Redhawks.

I’ve just scratched the surface about Redhawks. A more comprehensive article would be necessary to cover all the bases of this fine gun has to offer. Perhaps at a later date.