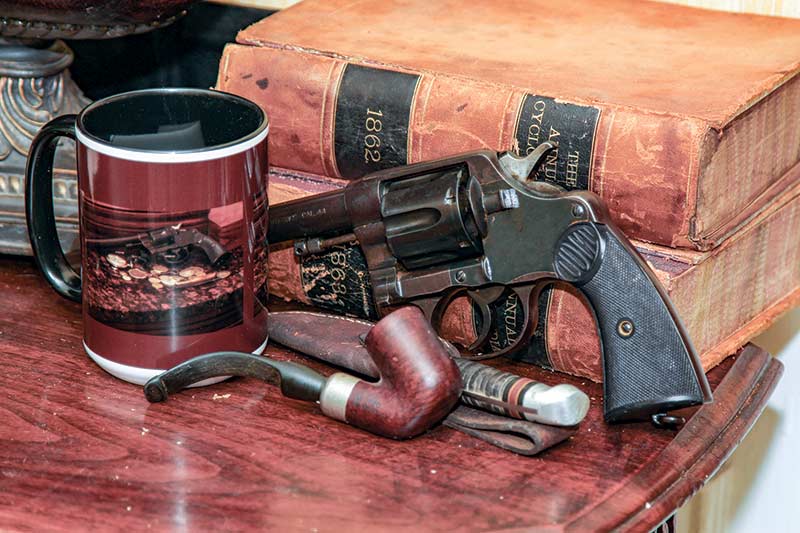

Rough History Reborn: Colt New Service Revolvers

The New Service revolver took the Western World by storm. Adopted by the Royal Canadian

Mounted Police, the U.S. Border patrol and other police and military organizations foreign and

domestic, it was chambered for the Black Powder era .45 Colt, the .38 and .44 WCF rounds

and various British large bore revolvers.

The New Service was introduced in 1898, 10 years after Colt’s first swing-out cylinder Army and Navy models. It was basically a large frame version of the earlier revolvers and shared the same lock work, including the small breakage-prone leaf springs that remained standard until replaced by coil springs a decade later. Even in its earliest form, the revolver won acceptance across the western world. Even early on, it was chambered for virtually every large-caliber revolver cartridge in America and Great Britain, later including the .38 Special and .357 magnum before being discontinued in 1942.

In 1962, I sent $22.50 to a Dallas mail-order house for a New Service model 1917 from The Great War. Chambered in .45 ACP, this model uses moon clips. A postal employee delivered it to the front door — happy with a 15-year-old’s signature.

It had the positive safety bar developed in 1907 and the device was so efficient it blocked the hammer even when the trigger was pulled. I removed it and tossed it away. The trigger pull was prodigious in weight with a long reach that must have challenged the average-sized shooter of the period. This was back in the day of the $2.50 per box 1942 steel-cased surplus ball that stuck fast to the chamber walls and had to be pounded out.

It was also the time of the “Poor Man’s Magnum” — a favorite subject in the pulp zines of the day that involved ladling in quantities of Unique or 2400 (!) behind cast bullets of 200–250 grains until the characteristic “BOOM” became a supersonic “CRACK” of nascent magnum-hood. Versions of these loads even made it into loading manuals. I shot the steel-cased ball and the Poor Man’s Magnum handloads and never blew the gun up. I can’t recall ever actually hitting anything with it and 57 years passed before I heard another New Service calling my name.

A Piece Of History

It occasionally appeared on a friend’s table at local swap meets and gun shows. It was an early .44-40 with an un-tapered 7½” barrel. It was made in 1906 when Theodore Roosevelt was President and the Panama Canal was under construction. If this revolver could talk … it would probably relate to a near-century abandoned on the floor of a barn be-pizzled and be-shat by cows and such. That is just how ugly the surface patina really was.

Flat springs do not wear well, and the action was “whocky” as anticipated. Still, held at a downward angle, it seemed to carry up to a tight lock-up, double or single action … some of the time. The positive safety block was not yet invented and the revolver might or might not go off if dropped on the hammer fully loaded.

The bore and chambers had survived corrosive primers and likely black powder cartridges and were free of pits. The underside of the gutta-percha grips bore three initials and the date 1915. The right-side panel had the near-universal missing piece above the bottom locating pin. Faintly visible was the revolver’s serial number scratched in a different hand. Despite the truly ugly patina, the address line, serial numbers, model designation and “.44 Caliber” were legible.

A Lick And A Promise

I ordered replica grips from GunGrips.com, then lightly corded the surface grimness with steel wool and followed up with multiple treatments of Birchwood-Casey Plum Brown and Super Blue until an even, dark finish emerged. The treatment doesn’t wear particularly well in a holster but is easily restored.

My friend Johnny Bates has won the respect of local collectors by restoring historic arms to working condition. He volunteered to fit the grips and held onto the revolver until they arrived. He quickly determined that while the flat handspring was present, it was not impinging on the hand. It looked like he might be able to cobble up a replacement from a percussion revolver part. His better idea led him to modernize the system via a ballpoint pen spring and J&B Weld. “The gun is working just fine,” he reported, “and I think it will last quite a while.”

Sure enough, the timing was perfect, the action was smooth and the cylinder locked up tight. It didn’t even require the extra shove from the advancing hand when the trigger is pulled — a characteristic so common with even slightly worn DA Colts and a major selling point in old Colt advertisements. The trigger pull reminds me of my old 1917 and weighs in at 8 lbs., 6 oz. on the scale. The double-action is long and heavy at 13 lbs., 6 oz. per scale and barbell plate.

Shooting

I got to the range with a box of MagTech 200-grain lead flat point rounds which, right in accord with suggested handloads, clocked 880 fps and seemed suitably mild for shooting in a century-old artifact. My first go was at a paper plate with a double-action shot from seven yards to establish zero. I followed that up with nine more, including a single miss from 15 yards. I was perfectly willing to stick with 15 yards with this relic, but by the time of my next visit, the range was under two feet of water. The 25-yard range was operational and the shooting results very instructive. I fired five single-action shots into a 6″ cluster, then another five double-action. The DA group was actually the better of the two. All were inside the nine-ring of the B27 target, with four well centered at about 4″. All shots were single-handed as shooters of the era generally considered using both hands to be excessively “precious.” Overall, the result of the project and the shooting results provide a gratifying excursion into the material culture of a bygone era.

The practical value of this venture into kitchen-table gunsmithing is severely circumscribed by the nature of the beast itself. The Colt double actions of 1889 and forward were a major component of 20th Century handgun development. Still, the utility of the delicate and complicated lock mechanism depended on highly skilled artisans now departed and a skill set completely at odds with economic realities and the evolution of production modalities. The New Service is best appreciated in the context of its historical milieu.

Subscribe To American Handgunner

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: