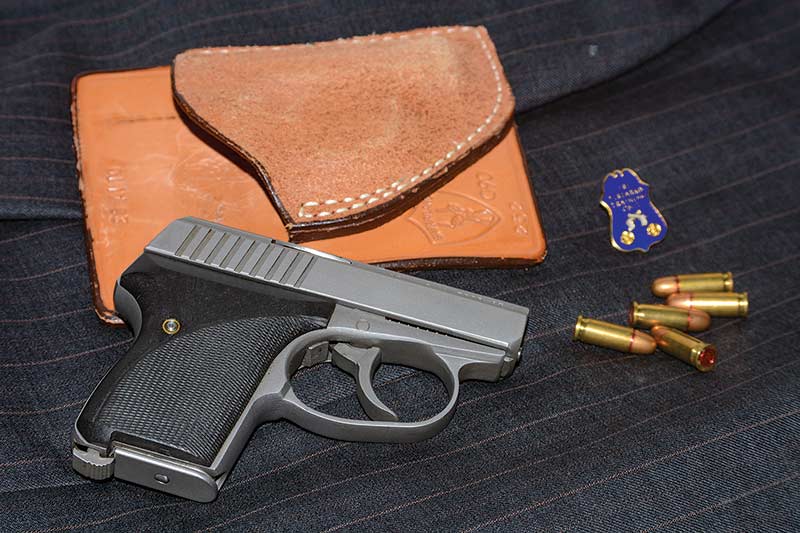

A Master Gunsmith's One-of-a-Kind: The Seecamp Compact 1911… Double-Action

When Wayne Novak tells you something is the best work he’s ever seen, you better listen. In this case, the gun he showed me was a compact M1911 with two slides and three barrels, capable of firing .45 ACP, .38 Super and 9mm.

The pistol started life as a full-size Colt Government Model, only to find itself cut down to compact dimensions. We’re all a bit spoiled now, but in those days before the Officer’s ACP, the only way to get a short Colt was to cut one into pieces and weld it back smaller. For those like me who nerd heavily on such things, George Nonte published a detailed description of how to do it in 1973 and it is fearsome.

Nonetheless, that’s precisely what was done to this gun, only so cleanly you can’t tell.

Elegant File Work

The frame was likely welded when shortened, as was the slide, but not where you might expect: The top corner of the thumb safety has been sliced off so the slide can be cycled with the safety applied. The corresponding notch in the slide was welded up. The alert reader will remember Charley Kelsey of Devel fame had a Hi-Power modified in that way and Devel 1911s often had matching bevels cut on the slide and thumb safety to accomplish the same thing.

The two slide tops were machined to create a low, flat rib lined with attractive serrations — bordered, no less — with a neat adjustable rear sight matched to a strikingly low front. All sharp edges have been flawlessly removed, and anyone who’s ever beveled a pistol can tell you how difficult it is to do this cleanly. Just aft of the ejection port, a pivoted loaded chamber indicator is installed — something Nonte also mentioned — and which he attributed to the French M1935-S pistol

Lockup Modifications

Almost all centerfire pistols 9mm and above fire from a locked breech, and modern ones use the square chamber area to lock into the slide’s ejection port. The 1911, however, uses locking grooves machined into the barrel forward of the chamber and which mate with similar lugs inside the slide. When you start shortening slides, those raised lugs limit how far back the slide can go, which is one of the reasons many compact M1911s use a flared muzzle; it allows clearance for the lugs to move past where the barrel bushing would usually stop them. On this pistol, the forward lug has been neatly removed from its Bar-Sto barrels, a solution that also appeared on the über-rare M15 General Officer’s Pistol manufactured at Rock Island Arsenal in the 1970s. The 1911 being as over-engineered as it is, this approach presents no safety problem and allows the critical amount of slide travel for the gun to function.

Double-Action?

And oh, it’s double action, which, for the cognoscenti, gives away the maker. Ludwig Wilhelm (“L.W.”) Seecamp is currently best known for his tiny stainless steel .32 pistol, the first hammer-fired double action only pistol made in the U.S. and the first stainless DAO pistol in the world. Leaving it at that breezes over too much, especially for a man whose work lives on in some of today’s most popular carry pistols.

The Seecamp Story

L.W. Seecamp was trained as a master gunsmith in pre-WWII Germany, a grueling process that could involve having to make your own gun — barrel and all — from raw steel with a file. John Lachuk’s description of the decade or so it took Augustus Pachmayr to become a master gunsmith is enlightening, especially in our current world where melting divots in a plastic gun is considered “gunsmithing.” Seecamp immigrated to America in the late ’50s and worked as a gun designer at Mossberg for a dozen years before retiring in 1971 and turning his attention to carry pistols.

There were few such guns from which to choose: the Browning Hi-Power was an option, as were the S&W M39 and Walther P38, all of which were 9mm (and the last two double-action), but the 1911 still loomed large. While he liked the 1911, Seecamp had fought — how to put this delicately — on the P38 side of WWII, and his combat experience had convinced him of the value of double-action pistols. He started converting 1911s to double-action by machining away part of the right side of the receiver, generally having to move the serial number, and adding a drawbar and pivoting trigger so the pistol functioned as a traditional double-action, but with the usual thumb safety and no decocker. In effect, it was the first double-action .45 anywhere, and Seecamp converted just under 2,000 pistols in the course of a decade until other competitive pistols appeared in the marketplace.

Pocket Pistol Diversion

He then pivoted to pocket pistols, the market for which had been dramatically limited by the Gun Control Act of 1968, which restricted the importation of most small handguns, such as the beloved PPK. Seecamp’s finely crafted .25 led the way in 1981, followed about four years later by a .32 and a .380 version in 2003, all of which are the same size externally. The second of those is the famous one: Basically, a .25 that just happened to be chambered for .32 ACP Silvertip hollowpoints; there was nothing like it on the market. The wait for one was in the years, and when you saw one for sale (generally, you didn’t), they could be several times the MSRP of $300 or so. This unicorn-like status held steady until competing .32 (and then .380) pistols appeared from NAA, Kel Tec, Ruger and others.

In the process of making little guns, especially ones that shot large-for-platform calibers, Seecamp learned a thing or two about recoil. This he distilled into a telescoping recoil system for which he received a patent in 1980. A substantial improvement on early dual-spring systems such as that used by short gun trailblazer Detonics, Seecamp’s telescoping recoil system was used in compact pistols by GLOCK, Colt, Kahr, Kimber and others.

Grip Safety ... Irrelevant?

Back to this little gun. In addition to the double-action mechanism, the mainspring housing and grip safety have been replaced by a single piece (much like the fully machined Novak Answer backstrap), the top of which is shaped into a wide, downward-swept beavertail. I understand eliminating any safety is a controversial issue. Modern shooting technique, however, creates a bit of a hollow in the shooting hand where it should contact the safety (hence the addition of all those bumps at the bottom) and causes the hand to put pressure on the underside of the beavertail, levering it back out to the “safe” position. At one time or another, most of us will miss it, and the safety won’t let the gun fire. It happened to me in a match, where I lost a little time. It’s a much greater risk on a carry gun, and eliminating it entirely is a solution few people (even those who have done it) are willing to write about, but that goes back as far as the Texas Rangers. On a double-action gun, it makes even more sense.

Bob Angell’s Gun

The most unusual part of this gun isn’t technically the gun at all: It’s the holster and the letters “R A” engraved on the bottom of the gun may give us a clue about why this is. This pistol was made for Robert “Bob” Angell, who surfaces in both the gun and custom knife worlds in the ’70s and ’80s. Angell worked with pioneering concealment holster makers Chic Gaylord and Paris Theodore of Seventrees (and ASP pistol) fame and was reportedly involved early on in using Kydex for knife scabbards and holsters. It’s hard to find much detailed information on Angell: He’s mentioned in Knives ’83 as the designer of a fixed blade and matching shoulder harness, but other than that, even the internet doesn’t have much to say about him. If you do, please email me care of this magazine, as I’d like to know more.

While I have no definitive information on it, it seems likely to me it was Angell’s idea to replace the top left grip screw of the Seecamp auto with a snap so the matching shoulder holster’s thumb break, rather than wrapping around the gun, snaps directly to it. Very clever, and the gun even came with a spare grip panel and snap insert.

After a century-plus, the idea of what a custom 1911 should look like is fairly crystallized. In the earlier days, though, imagination and craftsmanship created some very interesting pistols many of us have never seen, and this one is a prime example.

Special thanks to Wayne F. Novak and Anthony Lombardo.