The "Defensive" .22

Folly and Irony

When I first began shooting back in my early 20s, a lot of my trigger time was spent wrangling a GI-pattern 1911 in John Browning’s original caliber of .45 ACP. I didn’t want to admit it then, but I’m wise enough to acknowledge it now: It was too much gun for me. That old GI thumb buster didn’t tear my arm off or anything, but I certainly mashed the hell out of the trigger with each round I fired.

A few years later, I had the good horse sense to purchase a Ruger Mark II of my very own. I remember heading to the range and being downright stunned to find I could cluster the overwhelming majority of my shots inside of a silver dollar-sized target within seven yards. Quite truly, that Ruger helped build my confidence and stumble my way into an intermediate skill set.

The Big Question …

At about that point — and despite the ample volume of printed words I’d read attempting to dissuade me otherwise — an intrusive thought began to enter my brain. I would bet a number of our readers have entertained a similar notion. It goes a little something like this:

“If I can shoot my .22 fast, and if I know I can use it to make good hits,” I asked myself, “Why wouldn’t it be an acceptable choice for matters of self-defense?”

Today, I’m better equipped to answer that question for my past self. Not only do I find myself agreeing with conventional arguments against the idea now that I’m older and wiser, but I’ve formed a few thoughts of my own along the way

Traditional Cases Against

Understanding why nearly every expert will steer a user away from a rimfire pistol or rifle when choosing a defensive tool comes down, broadly, to two areas where the .22LR cartridge is questionable: reliability and efficacy.

We’ll start with reliability first. Obviously, there’s a fundamental difference in the way that rimfire and centerfire cartridges work. The heart of the centerfire cartridge is the primer. When struck, it will create a plume of flame that ignites the powder sitting just above it. You’re probably already aware of this.

In a rimfire cartridge, however, a priming compound has to be squirted into the case in liquid form, at which point the cases are spun so the compound ekes into the internal crevices under the lip of the cartridge rim. That compound then becomes impact sensitive once it dries. It’s a wonder the rimfire priming system works as well as it does; certainly, it’s a testament to the quality control of some of our favorite ammunition producers.

When comparing the inherent reliability of centerfire and rimfire systems in “real world” contexts, however, it’s not even close. I have to comb through my memory banks to think of the last time I had a dud centerfire round. Even in those cases, an unexpected “click” rather than a bang was due to an equipment malfunction or modification related to the gun itself. Weak springs are almost always the culprit, though a broken or out-of-spec firing pin is sometimes to blame.

By comparison, I encountered an uncooperative rimfire cartridge the second-to-last time I was at the range. When the impact of the firing pin failed to set the round off, I rotated the cartridge a half-turn in the chamber to give it a strike elsewhere on the rim — a process that becomes almost second nature to well-traveled .22LR shooters. That sent it.

Even seasoned rimfire shooters will tell you that a bad round, even from quality ammo makers, and when fed into excellent, well-maintained tools, is just flat out something that happens. That’s not an ideal quality in a defensive arm.

Let’s next address the question of efficacy. It’s certainly true that even a lowly .22 has the potential to end an assailant’s malfeasance. The problem lies in how well a rimfire projectile performs that task. Consider this: While a 40-grain, .22 caliber bullet travels at about the same speed as a 124-grain 9mm bullet (say about 1,050fps), it has a third of the mass and a third of the bigger object’s momentum and kinetic energy. Most .22 hollow points also tend to expand minimally, if they manage to at all.

It’s a little beyond the scope of our present discussion to get further into the weeds of the terminal performance of various rimfire loads. However, I’d invite our readers to explore the extensive ballistics testing performed by Chris Baker and the team over at LuckyGunner.com. Greg Ellifritz’s exploration of firearms’ stopping power, published online by the Buckeye Firearms Association, is further good reading.

The Skill Question

Let’s table all of the above for a moment and concentrate on the best case of the defensive .22: First, that all rounds fire without a hitch, and second, that all rounds are delivered rapidly and exactly where the shooter hopes to place them. Indeed, there are going to be a lot of our readers who know they can call upon their own rimfire handgun to dump six rounds into a head-sized target in about the time it takes a person to sneeze.

To those people, I say this: If you’re at that stage, you can probably shoot nearly as impressively and capably with a centerfire handgun.

Indeed, rapidly stacking rounds with a rimfire handgun requires not just good execution of the fundamentals, but also application of more advanced pistolcraft. In particular, the dudes who can pap-pap-pap three rounds into a softball-sized target already know how to get onto the trigger quickly and how to ride the reset. They’re going to be front sight or dot focused, tracking it through the recoil process, and touching the trigger off again when it settles. They’re also quite certain to have figured out the value of a good stance and shooting platform, which will allow them to drive the muzzle of the gun back on target.

Irony

And therein lies the irony, to me, of the “defensive rimfire” pistol: Anyone capable of using it as an effective self-defense tool would be better served by applying all of those skills to a centerfire handgun if a serious situation arises. The time to make a first-round hit is going to be virtually identical, and while a skilled shooter’s split times might be a bit worse going from rimfire to centerfire, they’re not going to be that much worse.

As a case in point, my own split times with a .22 handgun are about 0:22 seconds between shots. That’s if I want to be sure I’m placing my rounds as fast as I can into a generally “A-zone” sized target at seven yards with zero misses. If I switch to most of my 9mms, that increases to about 0.33 seconds. At least that’s the data from my last range trip; some days I’m a little slower, and some days I’m a little faster, but that’s usually the amount of time I need.

Now, you could look at that as an astonishing 50% increase in my split times, jumping from a .22LR to a 9mm handgun over two seconds. It’s the difference of getting another three hits on target between the smaller caliber and the larger. But, comparing the 40-grain and 124-grain bullets being launched, centerfire yields a 106% increase in the payload dumped into a particular target in the same amount of time. Food for thought.

What’s additionally interesting is exploring the notion of the “defensive .22” from the bottom of the skill ladder, where someone of limited hand strength and expertise desires a handgun for self-protection. This is a person who will likely be landing fewer shots in a given amount of time and placing them less accurately. In that context, wouldn’t it be a generally better idea to ensure that each of those rounds was as effective as possible?

But Could It Work?

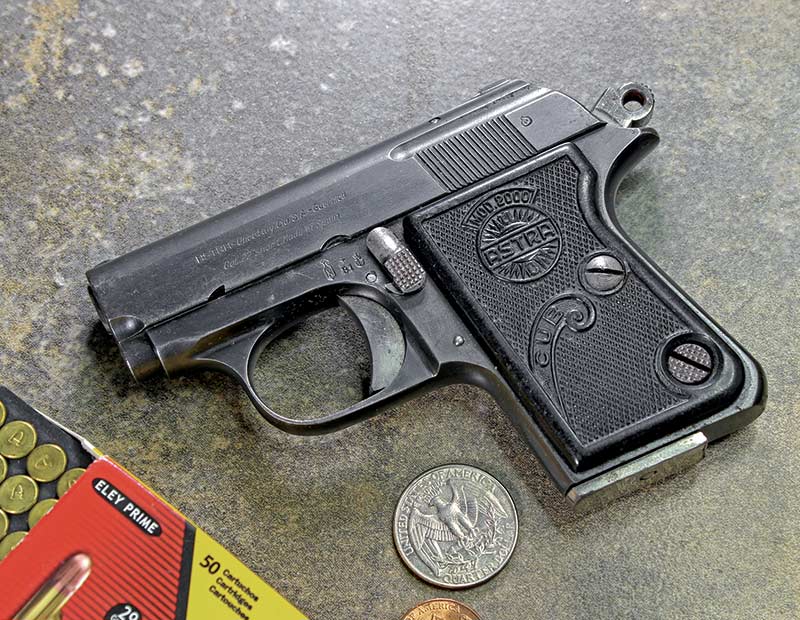

Certainly, a .22LR or .22 Magnum handgun has the theoretical benefit of size in its favor: The diminutive caliber permits firearms to be designed much smaller and lighter than an equivalent, CCW-intended gun in a centerfire caliber like 9mm or .45 ACP. My Astra Cub in .22 short is not what I would want to rely on to stop someone determined to do me physical harm. However, it can be stored in the fifth pocket of one’s jeans. Guns like this allow someone to go armed in contexts where it might not otherwise be possible.

A number of our readers may also point to a varying number of “tactical” .22s that have proliferated the market. Almost all of them are of similar size to their centerfire counterparts, and have very little similarity to the .22 target pistols of yesteryear. It’s easy to look at this class of firearms and conclude they were designed for some measure of defensive utility.

That said, I would wager most of us here at American Handgunner would argue the purpose of these guns is to serve as understudies for the big boys: With the low cost of ammo, it’s a lot easier to practice drawing, firing, reloading, and other actions requiring various “reps,” and then translating those skills to a more serious and similarly sized pistol. You’re more likely to practice on a platform that doesn’t beat your hands and wallet up.

As the saying goes, any firearm — even a mousegun or one in a rimfire caliber — is better than harsh words and has the potential to defend life and limb. There are, however, almost always better choices. Today, it’s hard for me to visualize any kind of shooter who would be best served by a rimfire firearm in any kind of defensive context. Especially and including people who can wield one very fast and accurately.