Cancer-Curing Chemical Weapons

December 2, 1943, was a Thursday. Allied troops worked feverishly in the freshly-liberated Italian port of Bari on the heel of Italy, offloading the ammunition and supplies required to support the ongoing fight against the Axis. Italy had capitulated three months before, but the Germans still fought like lions.

The port was fat with ships from America, England, Poland, Norway, and the Netherlands. On this very Thursday, British Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham, commander of the Allied Northwest African Tactical Air Force, stated, “I would consider it as a personal insult if the enemy should send so much as one plane over the city.” He would live to regret that.

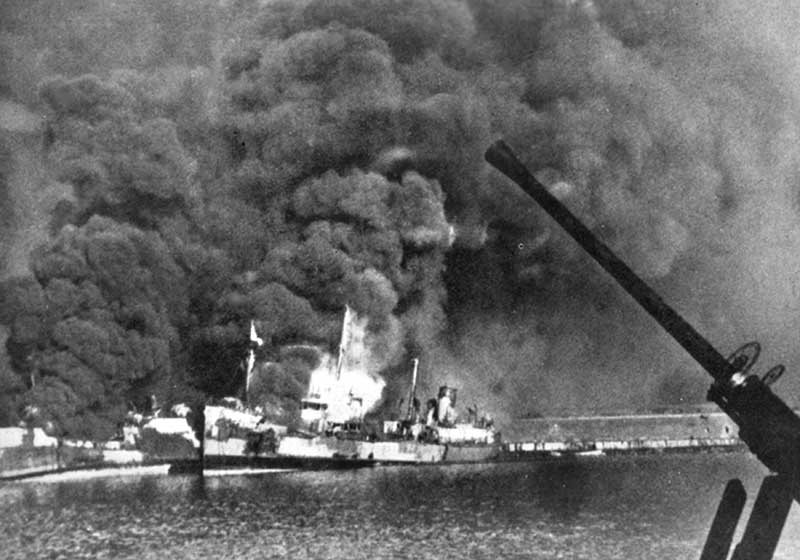

The Germans attacked with 105 Ju-88 A-4 bombers from Luftflotte 2 and achieved complete surprise. The raid spanned about an hour. The attacking Luftwaffe raiders sank 27 cargo ships in the harbor. More than 1,000 allied troops, sailors, and merchant seamen perished alongside roughly the same number of civilians. The Germans lost but a single plane.

That would be bad enough, but survivors pulled from the oily water also began to manifest horrific skin burns. Massive blisters formed on their flesh. Six hundred twenty-eight military patients were hospitalized, suffering from these ghastly injuries. Eighty-three of them eventually died.

At first, there was a suspicion that the Germans had attacked the harbor with chemical weapons. However, the truth was something potentially far worse. The details were immediately suppressed, but we had just inadvertently exposed our own troops to mustard gas.

Among the 27 sunken vessels was a Liberty ship called the SS John Harvey. Its top secret cargo included 2,000 M47A1 mustard bombs to be used in the event Hitler first employed chemical warfare agents on the European battlefields.

During the Luftwaffe attack, these diabolical weapons had broken open, and the mustard agent had mixed with the fuel oil spilled into the harbor’s waters. The results were predictably horrifying.

Adolf Hitler was likely among the top five worst people who ever lived, and the experience he had with chemical agents during World War I kept him from using these dreadful things in World War II.

In the face of such an epic tragedy, Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Francis Alexander, a chemical warfare specialist on Eisenhower’s staff, was sent to Bari to investigate. He immediately identified mustard gas exposure. Alexander’s “Final Report of the Bari Mustard Casualties” was predictably classified.

Lt. Col. Alexander’s superior officer at the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) was Colonel Cornelius P. “Dusty” Rhoads. This was a citizen Army drawn up for the global conflict, and these guys came from all walks. In his previous life, Dr. Rhoads had served as head of the Treatment of Cancer and Allied Diseases Department at New York’s Memorial Hospital.

Col. Rhoads had an unprecedented opportunity to study hundreds of victims of mustard poisoning. He observed that the mustard agent suppressed cell division. Using his experience in oncology as a basis, it occurred to him that mustard agent might be used to inhibit the rapidly reproducing malignant cells that drive cancer.

Every day the human body creates around 330 billion new cells. Almost all of these cells demand that the entire genome be reproduced. Each of these packets of genetic information includes around 3.2 billion base pairs. Given that astronomical volume, mistakes are inevitable.

God designed us with proofreading mechanisms that catch most of these mistakes and destroy the aberrant cells before they can do any damage via a process called apoptosis. However, if one of these cells is almost but not quite normal, it can slip through that net and morph into cancer. These cancer cells typically multiply faster than normal cells and in an uncontrolled fashion.

Col. Rhoads became convinced that the active ingredient in mustard gas could be used, in very small doses, to attack rapidly-metabolizing cancer cells.

After the war, he approached Alfred Sloane and Charles Kettering to fund the Sloan Kettering Institute for Cancer Research (SKI). These two men had made fortunes off of war production through General Motors. The resulting cutting-edge research facility was manned by scientists no longer needed for the advancement of war goals. They proceeded to synthesize mustard derivatives into the first effective medications for cancer. Nowadays, we call this chemotherapy.

In 1949, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Mustargen (mechlorethamine) as the first experimental chemotherapy drug in America. It was used to successfully treat non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. This effort planted a seed that became the flourishing field of oncology today.

Thanks to this serendipitous discovery and a lot of hard work, cancer is no longer the death sentence it once was. Today, chemotherapy agents specifically target rapidly-metabolizing malignant cells while selectively sparing the healthy stuff, but there is still some overlap. That’s why many patients undergoing chemotherapy lose their hair because hair cells metabolize quickly as well.

The attack on the Bari harbor in 1942 cost some 2,000 lives. However, the American Cancer Society has since described the Bari attack as the beginning of “The Age of Cancer Chemotherapy.” Millions of people have had their lives saved or extended due to research that spawned from that terribly dark day.