Customizing A Ruger Wrangler

Have We Lost Our Minds?

Hitting the “affordable quality” bull’s-eye is a target chased by most everyone who manufactures anything — if they’re smart, that is. Ruger’s launch of the $250 Wrangler single action in 2020 smacked that bull’s-eye dead center. Since then, sales have been strong and legions of plinkers, hikers, casual handgun hunters and anyone needing a rugged “working” pistol were drawn to the Wrangler like a 3-year-old drawn to a plate of Oreos.

I’ve had about a dozen or more Wranglers come through my hands, including the Birdshead models, and while they are all obviously built to a price point, I’d call them “utilitarian” — not cheap. Money normally spent by Ruger on final finish work, forged steel innards and wooden grips is saved, and this savings is passed on to us happy gun buyers.

I was chatting with Hamilton Bowen of Bowen Classic Arms about the Wranglers, and it seems he too finds himself drawn to them for the same reasons we do. How much fun can be had for around the $200 mark at many stores? Plenty if it says Wrangler on it. But Hamilton really got my attention when he said he was customizing one for a client. Huh? What? I confess I hadn’t thought of that — ever. I had taken one, slicked the action up a bit and even re-cut the muzzle crown, but a “full custom” on a Wrangler?

Then I realized it was a great idea. People put $1,500 into a $300 Ruger 10/22 for the same reason. Why not put some time and money into a Wrangler? I suddenly started to look at Wranglers as affordable “base” guns rather than price-point plinkers.

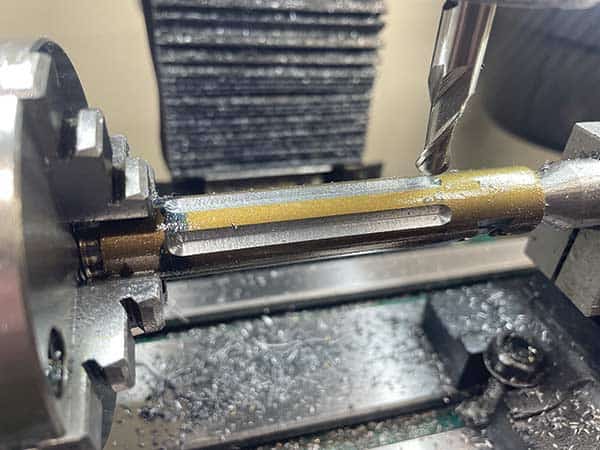

The result is a clean forcing cone and square barrel end. Roy followed

this up with some lapping with the correctly sized brass lap turned just

as the cutter was turned using a rod from the muzzle. Starting at 220 grit,

he then went to 400 and finally 600 grit compound. Likely overkill, the results were amazing.

Solid Bones

The Wrangler uses a machined cast aluminum alloy frame, zinc alloy grip frame and hammer-forged steel barrel and cylinder. The action parts are all MIM steel alloy but otherwise mirror the forged steel insides of the more spendy Single Six-style revolvers. The final gun is Cerakoted in silver, black or burnt bronze and, frankly, looks very good. Some limited runs by various distributors have offered other interesting colors, and of course, anyone could do their own gun over using Duracoat or Cerakote if they wanted something unique.

The twist rate of that barrel is 1:14″, and the ones I’ve examined with a borescope have shown sharp rifling. Sights are classic fixed, and the transfer bar means you can carry it loaded with six safely. The coil springs mean virtually no chance of a broken action spring of any sort, and the grip-frame shape offers the ability to take dozens of custom grips offered from the likes of Premium Gun Grips (like those on our sample gun here), Altamont, Eagle and even Ruger, to name just a few.

These mean the Wrangler is “all there” and an excellent base gun to customize. The affordable price also means it’s a great gun for a novice to practice on. You can start with some easy things first, like an action job, and then keep going as your skills develop. Keep in mind what I did to my gun could be done to just about anybody’s single action, while many of the techniques can be applied to a wide range of guns and work done to them. Don’t think of this as just customizing a Wrangler, but more of an idea pool for many of the guns you might have.

Fully disassembled, the Wrangler is ready for action work. Use hard

stones of several shapes and sizes to polish the bearing surfaces. Keep

in mind you’re not removing metal here, only polishing. See about reaching

into the frame area channels to work out any casting imperfections, burrs or

glitches. Don’t overdo things here — just a few passes with the hard stone

is likely enough.

Here’s the loading gate spring. The right-angled bit near the stone

rides against a cam surface on the bottom of the loading gate. Polish

both bits, but don’t change any angles. If you give the spring a gentle

squeeze, you can bend it slightly together, allowing an easier opening gate.

It doesn’t take much, so go easy and try it out. If you bend it too far, the gate

will be sloppy and loose, and you’ll need to bend it back some.

MIM parts are fine, but the flat sides of the hammer and trigger were

wavy, so Roy flattened them using a flat aluminum sanding block from

Harrison Design. You can use a flat metal plate, glass or anything similar.

Start at 180 grit and go to 220 for a nice, satin look. You can see the

flat area starting to form here.

The Tools

I’ll admit right off I used a medium-sized milling machine, a lathe and related tooling (cutters, clamps, indicators, etc.) as part of this build. But I also used a wide range of hand tools like files, stones, wet-or-dry abrasive papers, gunsmith screwdrivers, muzzle and forcing cone cutters, a Foredom tool (like a Dremel), diamond hones and various cutting fluids, lapping and polishing compounds and lubricants. I also used other tools like picks, a small level, borescope, vise, canned “air” to clean chips away, a magnifying visor, torque wrench and other tools I’ve collected over the years.

But don’t let any of this scare you away. A few good files, screwdrivers, wet or dry paper, a few hard stones for action work, a modest vise and a clean, well-lit place to work can get you going. As you find yourself wishing for a particular tool to accomplish a job, then you buy that tool. They’ll gradually accumulate, and pretty soon, you’ll have a 25-foot workbench as I do!

The hammer spring can stand with some thinning to lighten it.

Don’t clip coils on any spring, as that changes the dynamics. Note

how the spring coils are slightly “flat” in the photo. Slip the spring onto

a metal rod and touch it against a spinning belt sander to reduce the diameter.

Don’t go too far, and don’t overheat things. Just flatten it a bit and try it.

Polish the guide it rides on too.

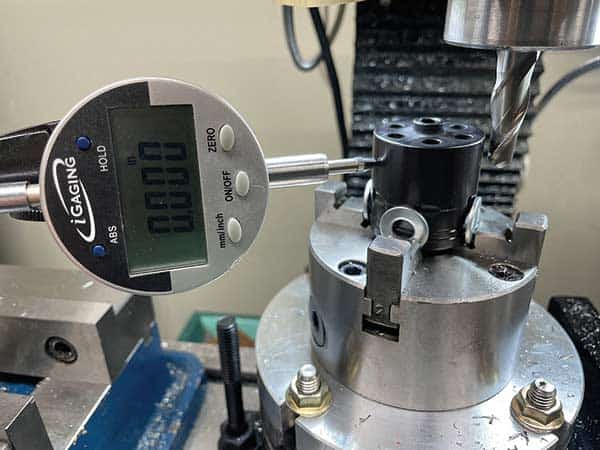

Prior to fluting the barrel in the mill, the barrel had to come off to

make things manageable. Roy found it unscrewed surprisingly easily

and was held on with some sort of Loctite or glue. Wrapping the barrel

in 220 grit paper and locking it in the vise allowed him to unscrew the

frame easily with the “hammer handle through the cylinder cut-out” method.

The Build

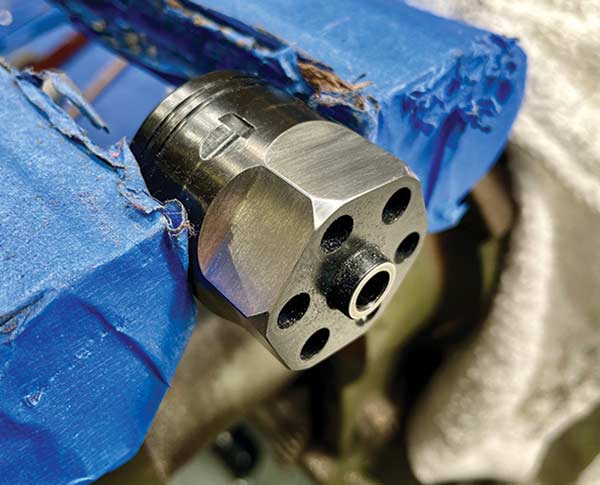

We’ll do this as a sort of step-by-step process so just follow the photos along, and they’ll be in rough order. Keep in mind much of this is more “just to show you” the steps than a detailed how-to-do-it. When I say, “I set up the cylinder in the rotary table,” there’s a lot of dialing-in and indexing, making sure the parts are clamped correctly, milling table square and locked, etc., which we don’t have space to go over. Fortunately, there are thousands of YouTube videos and resources online if you have specific questions about some details.

Feel free also to skip steps as needed. You can ignore the portion on cutting the flats on the cylinder, for instance, and go right to another step if you like. Most custom work shown can be done as a standalone modification. Also, I was working on black and burnt bronze guns, so you’ll see both colors in the steps.

For more info:

PremiumGunGrips.com;

Brandon’s Gun Trading Company (Cerakote): (417) 623-8787; Brownells.com (for tools);

HS-Custom.com

(Custom Wrangler work)

One of the final jobs was to carefully work out any casting lines

or imperfections using fine files and abrasive paper grits. The

Cerakote shop said to take it down to 220 to 300 grit as a final finish.

They would then do a light sand-blast to even things out. This step

removing the casting lines made a huge difference in the final look of things.

Ta-Da! Grips are from Premium Gun Grips, and a set of custom

grips really spices things up. Some like the two-tone look, some

don’t, but Roy does, and since it’s his gun, that’s what counts.

It’s very satisfying to have a project like this where you did the

work yourself. You could easily do this same sort of thing and

simply leave off the fluting. The rest would still make a handsome,

smooth operating Wrangler. HS Custom in Joplin can also do this

work if you’re not game to tackle it yourself.

Take your time and be aware you may have to remove a bit of

coating here or there to get things to fit. Lube as needed as it

goes together, and don’t force anything. The pins can be fumbly

but don’t be tempted to pound them in. They’ll slip in; you just

need to get things aligned “just right.” It’s exciting to watch it take shape.

Here’s what it’s all about. The “new” Wrangler at home in a Thad Rybka

field holster is ready for a day on the tractor, hiking, hunting or just sitting

on your desk to be enjoyed. Remember, you can start with simple jobs like

an action job and become more adventurous as your skills build. But don’t

be askeert to give it a try.