Field Trips with Dad

Washing the sleep from his eyes, the boy was excited. On mornings like this, unlike school days, he didn’t mind getting up early. No sir, today he was going on a special trip with his dad. After brushing his teeth and combing his hair, the freckle-faced boy slipped into Wrangler jeans and a plaid shirt with pearl snaps. Last came his boots and cowboy hat, just like dads.

His boot heels clip-clopped against the hardwood floors, skipping his way to the kitchen. Grinning, he smelled the aroma of frying bacon mingled with cigarette smoke. He loved days like this when it was just him and Dad getting ready for some kind of adventure or fun outing. Flipping the bacon with a fork, his dad asked, “You ready to learn something about Pancho Villa?” The excited boy responded, “Yes, sir!”

With the bacon done, his dad cracked four eggs into the grease as toast popped from the toaster. “Grab that toast and put in two more slices. These eggs should be finished so we can eat,” he said.

The Trip

Sitting in the warm pick-up truck with a full belly and anticipation surging through his body, the boy noticed they were headed south as Hank Williams played on the radio. “It’s only a half hour drive to get there,” his dad told him.

Pulling into a small village, he saw a small building. It was a museum. The boy’s eyes widened when he spotted the 3-inch artillery piece, along with an old wagon and some type of armored vehicle sitting out front. For a 10-year-old, it didn’t get any better.

“Son, I’m going to tell you the historical relevance of this place. You may not appreciate it now or quite understand it, but you will each time you visit here. Let me tell you how it all started …”

Battle of Columbus

The Battle of Columbus, also known as the Columbus Raid or The Burning of Columbus, began in the early hours of March 9, 1916, by the remaining soldiers of Pancho Villa’s Division of the North. The small town was three miles north of the Mexican border. The raid grew to a full-scale battle between the U.S. Army, joined by some townsfolk, against the Villistas. Villa’s men were driven back by the bravery and tenacity of the 13th Cavalry Regiment stationed there.

This surprise attack infuriated Americans. It caused a punitive military reaction, further complicating Mexican-American political relations. President Woodrow Wilson responded by sending General John “Blackjack” Pershing and his troops into Mexico. Called the “Punitive Expedition,” they invaded Mexico but failed to capture Villa.

Background

Pancho Villa was no fan of Mexican President Venustiano Carranza, fighting against him and his Army whenever possible. During the Mexican Revolution, Villa sustained his greatest defeat during the 1915 Battle of Celaya. Villa’s Army, The Division of the North, was now disorganized, wandering around northern Mexico, short on food, military supplies, money and munitions. To continue his war of opposition against Carranza, Villa figured raiding Columbus, New Mexico would be a good way to obtain needed supplies.

Villa planned the attack, camping his army of an estimated 1,500 horsemen outside of Palomas on the border three miles south of Columbus. The area was populated by about 300 Americans and about as many Mexicans, which fled north from the advancing Villistas.

Villa sent spies into Columbus before the raid and they mistakenly told him only 30 troops were in town. In reality, there were 12 officers with over 340 troops from the 13th Cavalry, of which 270 were combat troops. On the night of the attack, half the men were on patrol or other assignments.

The Attack

Villa divided his force into two columns, most approaching town on foot, launching a two-pronged attack at 4:15 a.m. on March 9. When the Villistas entered Columbus from the west and southeast shouting, “Viva Villa! Viva Mexico!” and other phrases, the town’s people, along with most of the garrison, were asleep. They woke to an army of Villistas burning their buildings and looting their homes.

Battle Stations

Despite being taken by surprise, the Americans quickly recovered. Soon after the attack, 2nd Lt. John P. Lucas, commanding the 13th Cavalry’s machine gun quarters organized a hasty defense around the camp’s guard tent, where the machine guns were kept under lock, with two men and a Hotchkiss M1909 Benet-Mercie machine gun.

Lucas was soon joined by the remainder of his unit and 30 troopers armed with armed with M1903 Springfield rifles, led by 2nd Lt. Horace Stringfellow, Jr. The troop’s four machine guns fired over 5,000 rounds apiece during a 90-minute fight, their targets illuminated by the fires from burning buildings. In addition, many of the townspeople were armed with rifles and shotguns.

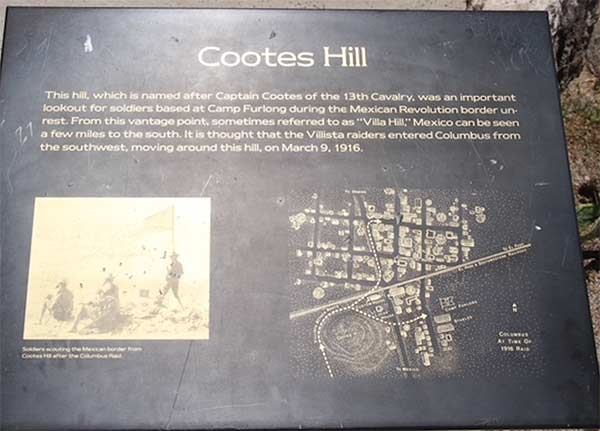

Villa’s men looted and burned several houses and commercial buildings while fighting civilians defending their homes. It’s not confirmed if Villa was with the actual raiding party at any time. Villa and his commanders took up position on Cootes Hill overlooking Columbus. From this location, they could observe the battle while some of Villa’s men acted as sharpshooters.

Aftermath

The raid left 18 Americans dead, both civilian and enlisted personnel. Outraged, President Wilson ordered the U.S. Army, led by General Pershing to hunt down Pancho Villa. National Guard units from all over the United States were called up. By the end of August 1916, over 100,000 troops were on the border. The Army used Curtiss Jenny airplanes for reconnaissance, along with trucks carrying supplies, both firsts for the Army, during the operation. They scoured portions of northern Mexico for six months for Villa to no avail.

Significance

With the use of Jenny airplanes, the raid is sometimes referred to as the birthplace of the U.S. Air Force. The raid resulted in the deaths of 70-75 Raiders, 10 Americans and eight soldiers. It also marked one of the few times foreign forces attacked the United States.

Real Time

The boy listened intently as his dad told him the history, stories about the men and Pancho Villa. They’d visit regularly after reading more about the raid and Pancho Villa himself. Naturally, they’d talk about the guns used by the men involved.

There’s a hill near the barracks providing a nice view into Mexico. The boy and his dad always climbed it, finishing their visit, looking south for signs of Pancho. It was the same hill from which Villa and his men watched the raid.

I first visited Pancho Villa State Park about 10 years ago when the very boy took me and Doc Barranti. The boy, now grown, was Bart Skelton — Skeeter Skelton’s son. It made the park visit more personal and interesting with Bart as our tour guide sharing his stories with us. After the tour, we climbed Cootes Hill, just as Bart always did, only now he shared the experience with Doc and me.

Southwest history is rich with stories like this one. Stories that entertain while teaching the lessons of rugged men living dangerous lives. They’re especially good when shared with a good amigo leading the way. Thanks for everything, Bart.