Lessons from Mike Plaxco

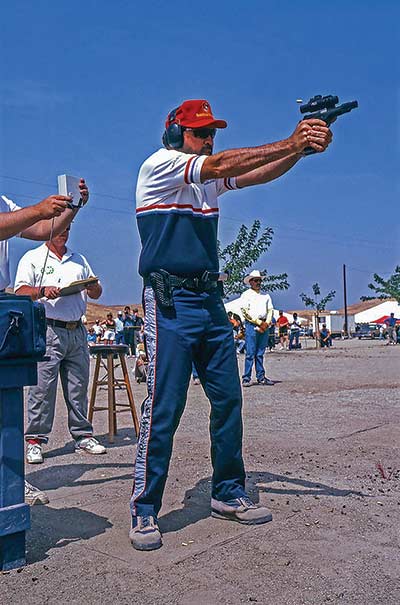

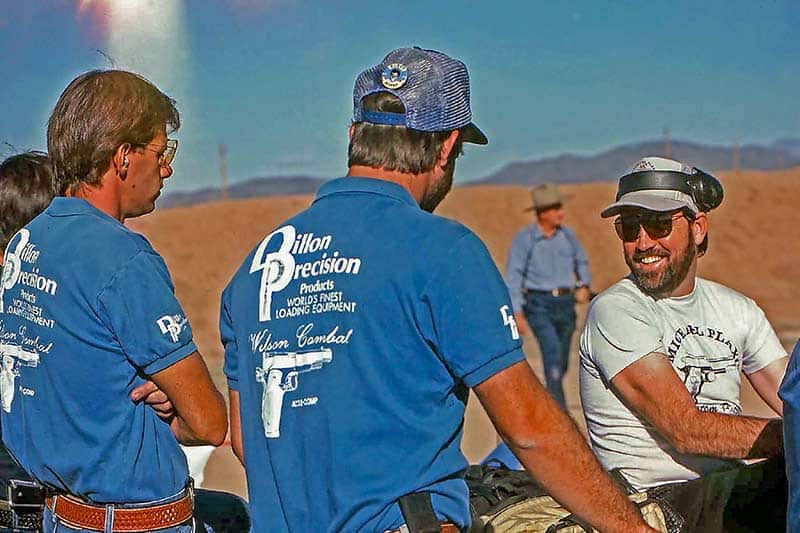

J. Michael Plaxco died recently, too young, a few months short of his 70th birthday. Mike was one of the early superstars of practical shooting competition, winning the IPSC National Championship (pre-USPSA) and the Steel Challenge in the early 1980s. There was little industry sponsorship for even the best shooters in those days. Mike mostly paid his way by building competition pistols, designing the Plaxco compensator (one of the first expansion-chamber comps), teaching classes and writing.

The best money I ever spent learning to shoot was on instruction from top shooters such as Plaxco and Rob Leatham. I’d encourage anyone who really wants to become a good shooter to do the same. I know. Training costs money. But without some kind of guidance, your time and money will produce results slowly at best. At worst, you’ll spend years learning bad habits.

In 1985, it was a humbling lesson to see Plaxco shoot a match at a level far beyond anything I had ever seen. I took a three-day seminar from Mike the same year, and by good fortune, it was a small class, so each student got lots of attention. Mike was a very upbeat, enthusiastic, cheerful person who liked people and liked seeing them improve.

Plaxco was also a highly intelligent and articulate person. He had an analytic mind, he could figure out what worked and why, and he could communicate his ideas. I don’t think he had any formal training as a teacher but he seemed to understand the basics of effective teaching, one of which is repetition. He expanded his teaching notes into an excellent book, Shooting from Within.

Four Basic Requirements

In that seminar long ago, he repeated what he then considered the four basic requirements for learning to shoot. It’s a tribute to his teaching I remember them clearly after nearly 40 years.

1. Accuracy takes precedence over speed. The foundation of good shooting is the ability to hit the target on demand. Speed comes from smoothness and develops naturally over time. If you focus on speed, the accuracy will never come. The old gunfighters expressed the same concept in pithy phrases: “Speed’s fine, but accuracy is final.” And, “Take your time, fast.”

Mike suggested around 200 rounds per training session. Fifty rounds are barely enough to maintain skills. On the other hand, most shooters lose focus if they shoot too much. Break training days into morning and afternoon sessions of 200 rounds each.

He advised beginning and ending every session with 10 or 20 slow-fire, precision shots striving for maximum accuracy. Doing so improves sight focus, trigger control, hold and stance consistency, and mental discipline. He once commented that few shooters have the mental discipline to fire 20 straight A-zone hits — at any range. Mike also taught that whatever skill one is practicing, one should always be scoring 90% of the available points.

2. The sight picture dictates the cadence of fire. In bullseye and precision shooting events, only the perfect sight picture is acceptable. In practical shooting, there are an infinite number of acceptable sight pictures depending on the difficulty of the shot. You should be shooting as fast as possible while maintaining an acceptable picture. The cadence of fire is very different for a full target, five-yard shot than for a partial or moving target at 25 or 50 yards.

3. You must learn to recognize an acceptable sight picture for the shot required. At three yards, a glimpse of the top of the slide may be acceptable; at 10 yards, you might need to see the front sight clearly on target; at 50 yards, the perfect picture of the front sight framed in the rear sight notch. Moreover, what is acceptable can vary with each individual.

When Jerry Barnhart was winning multiple national titles, his speed was simply phenomenal. After he had smoked a tough stage, I recall someone asking Barnhart what sight picture he saw while shooting so fast. Jerry thought for a moment and then replied, “I saw what I needed to see.”

4. Until the sight picture is acceptable, do not break the shot. Again, it relates to discipline — knowing what you are doing. Plaxco was a great believer in calling the shot based on the sight picture as the shot broke. He said, “If you tell me the shot was a D at 9 o’clock, and the bullet hole is a D at 9:00, you are learning. If it’s an A and you don’t know how it got there, you haven’t learned anything.”

Mike left us with one last lesson: “When all else fails, align the sights on target, take up the trigger slack and press the trigger straight back.”