Nosedive And Feed Angle In The 1911 .45 ACP

Science Comes To The Rescue To Help

Explain This Frustrating Problem

You finally get to the range for some fun. You insert the magazine, rack the slide, and — it jams. The round has nosedived into the feed ramp and stopped dead

These types of malfunctions are frustrating, but can often be cleared with a whack to the gun. In severe cases, you have to drop the magazine and start over. But why do rounds nosedive? Don’t they feed at the same angle as the magazine’s feed lips? Nosedive is not limited to 1911’s and is common to pistols with single column magazines and some double column magazines. Let’s explore just why this is.

The Nosedive Gap

Nosedive stoppages usually occur with more rounds in the magazine. As the number of rounds diminishes, so do nosedive problems. This is because the angle of the rounds in the magazine is different depending on how many rounds are loaded. As more rounds are loaded, their angle changes and they don’t point as high, becoming more perpendicular to the back of the magazine.

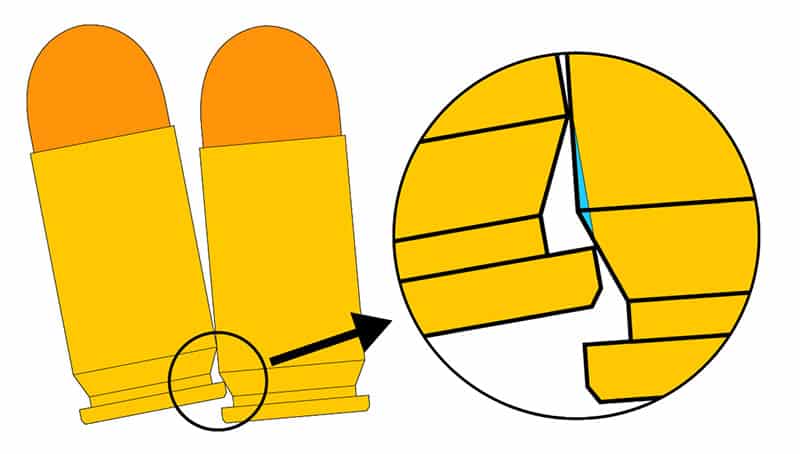

At some point, a gap appears between the front of the top round and the one under it because they take on different angles. This gap gets bigger as more rounds are added, at least in most magazine designs. The gap means the top round is free to pivot, which is what happens during a nosedive. The bigger the gap, the greater the potential nosedive.

Why does the nosedive gap form? The rounds are slightly offset because they lie at an angle. The rim of the top cartridge is positioned over the extractor groove of the underlying cartridge. The pressure from the magazine spring encourages the top round to tilt upward.

Mechanics of Nosedive

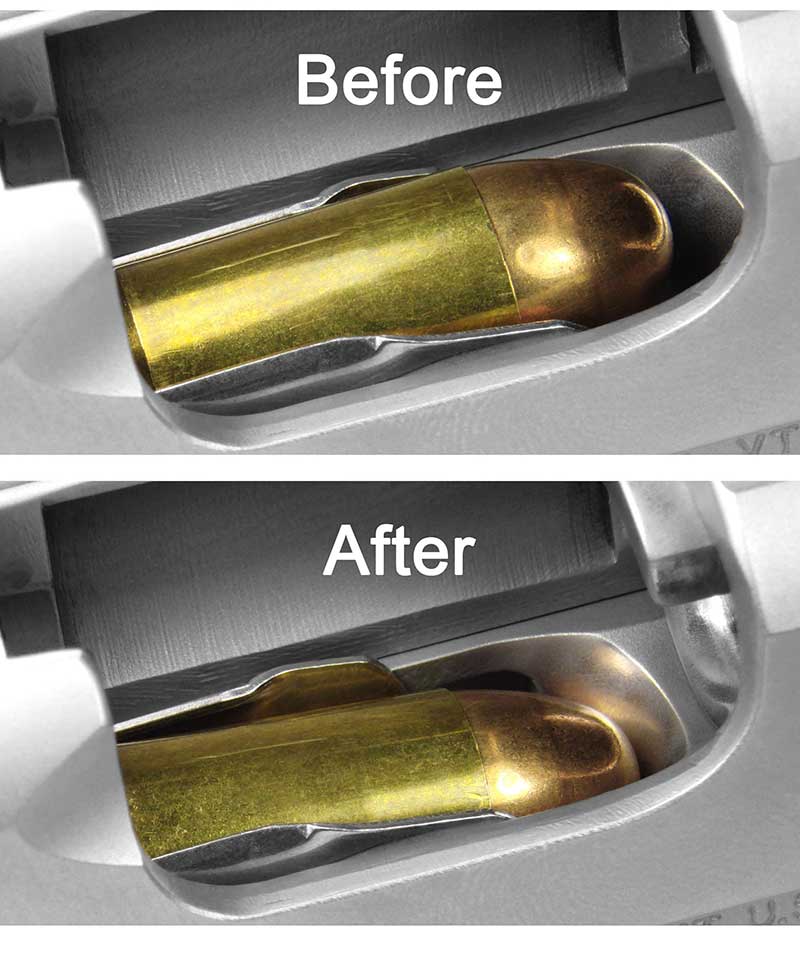

Several forces contribute to ensuring nosedive when there is a gap. First, the slide only pushes on the upper base of the cartridge since that’s the only portion above the frame. This lop-sided contact enhances downward tipping. Because the cartridge’s rim is in the underlying cartridge’s extractor groove, it would have to push the underlying column of rounds deeper into the magazine in order for it to move forward without nosediving. This would require considerable force since they are heavy and under spring pressure.

Instead, the rim increases drag and encourages the round to tip downward as it moves forward until it lies against the underlying round, or the bullet nose hits the feed ramp, whichever comes first. As a consequence, the round’s feed angle is close to the angle of the underlying round.

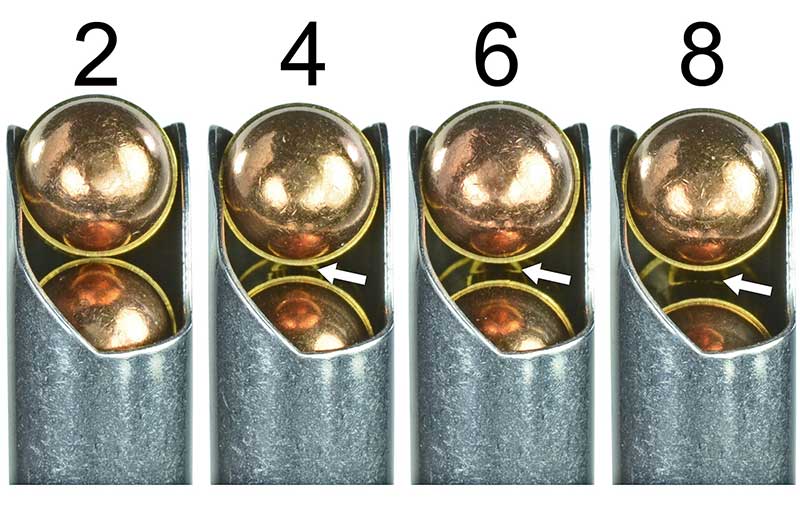

Here we see the size of the nosedive gap as the number of rounds increases (small white arrows

under top cartridges). The number indicates the number of rounds in the magazine. There is no gap

with two rounds, but a small gap is present with four rounds, and it gets larger as more rounds are added.

Note the underlying cartridge changes angle.

Feed Angle

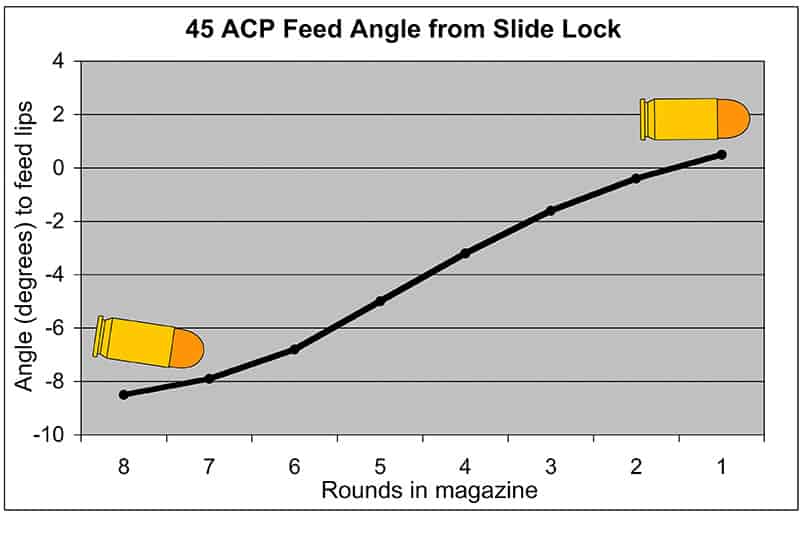

Since the size of the gap and the angle of the underlying round depend on how many rounds are in the magazine, each round feeds at a different but predictable angle. The first round out of a fully loaded 1911 magazine nosedives the most and hits lowest on the feed ramp because it has the largest gap. Subsequent rounds have smaller gaps and they hit higher and higher on the feed ramp as the round count wanes. The last round from the magazine feeds at the highest angle.

Cartridge feed angle was measured in the laboratory and at the shooting range in a single column 1911 pistol with Federal American Eagle 230 grain FMJ ammunition with an average overall length of 1.263″.

In The Lab

The gun (with the firing pin removed) was held in a vise and was video recorded with a high speed digital camera (1,000 frames per second) as ammunition was stripped from the magazine and chambered. All rounds from a fully loaded magazine were video recorded as the slide stop was released and the slide shot forward under recoil spring pressure.

Video of 186 rounds (24 full magazines) was analyzed for cartridge angle. Measurements from the video determined the round’s feed angle, which is its lowest angle prior to hitting the feed ramp. Magazines with 7- and 8-round capacities from Colt, Clark, Kimber, McCormick, Springfield Armory, Tripp and Wilson Combat were used.

Measured feed angles are shown in Figure 4. The left (Y) axis of the figure is the feed angle of the cartridge relative to the angle of the magazine’s feed lips. With eight rounds in the magazine (far left), the cartridge nosedives the most and its average angle is 8.5 degrees below the angle of the feed lips (-8.5˚). Subsequent rounds have progressively higher angles. The last round (round one) has an average feed angle of 0.5˚, which is only slightly higher than the angle of the feed lips (0˚).

If there was a nosedive gap, the round nosedived. Always. The change of angle closely matched the size of the gap. Sometimes it was less, sometimes it was the same, and sometimes it was more. Yes, there were clear examples of nosedive without a nosedive gap. The forces causing nosedive can be strong!

Live Fire

Feed angle was also measured at the shooting range. The gun was fired in a Ransom Rest and 155 rounds were video recorded.

Feed angle was about two degrees higher during live fire. Why? During live fire the top cartridge tends to be just forward of the rear of the magazine when it is pushed up to the feed lips. When the cartridge is farther forward, it does not have as much distance to travel before it hits the feed ramp. The round’s forward positioning could be due to movement from recoil and/or being dragged forward by the slide. The higher feed angle during live fire might help to explain why some people experience nosedive stoppages during hand cycling but not so much when shooting.

Summary

Nosedive is normal in single column magazines because of how rounds stack. As more rounds are added, cartridge angle changes, which ultimately affects feed angle. As a result, each round feeds at a different angle. Double column magazines are less prone to nosedive if they are properly designed to prevent the nosedive gap from forming.

Editor’s Note: We all know the 1911 platform can be very reliable. It’s important to understand there’s a need to experiment with different magazines to find which combination works best with your particular 1911, or other auto pistol. Live fire is an important part of that testing due to the many variables encountered during live firing versus hand-cycling. Chances are good, factory-supplied magazines may likely work best in a particular platform. Roy Huntington, Editor, American Handgunner

Resources

ANSI/SAAMI booklet Z299.3-1993. American National Standard. Voluntary Industry Performance Standards for Pressure and Velocity of Centerfire Pistol and Revolver Ammunition for the Use of Commercial Manufacturers. 1993. Sporting Arms & Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute, Inc., Wilton, Conn. USA.