Colt .22 Service Model

ACE Pistol

A Family Heirloom Designed In ... Prison?

I met Joe and Reecy Ireland at a church in Fayetteville, NC, shortly after being stationed at Fort Bragg upon my return from Vietnam. The Irelands invited me to their home where I found their 17-year-old daughter Joyce a delightful companion. So delightful, after a few months I convinced them to sign the permission slip to allow her to marry me. This was in 1973. Through a miracle or two, I’ve managed not to run her off.

Joe and Reecy were married in 1946. A Navy ensign, battle of Midway veteran and combat patrol submariner, he was one of two USS Drum enlisted men selected to attend naval officer school. The training took Joe to GA Tech in Atlanta, where he later met Reecy. At the time of their marriage, Joe had been transferred to Norfolk, Va., where he was on the Admiral’s staff for the battleship USS Wisconsin.

Before CCW Was Cool

An elder relative gave the couple a monetary gift with which Reecy planned to buy silverware. However, Joe felt she needed a gun instead. She was a small, pretty, young girl who would live in a military town while he was away from home. Before they left Atlanta for Norfolk, Joe bought her a $45 gun from a small shop in downtown Atlanta. Joe took Reecy shooting on her family’s land and she hit the bullseye every time, which surprised and pleased him. He deemed her ready to carry. Reecy, who is now a spry 91-year-old, told us she carried the gun in her purse with her everywhere she went, which included frequent trips on a ferry between Portsmouth, where the couple lived, and Norfolk, where she did her shopping, attended church and took organ lessons. That’s amazing when you learn she only weighed 98 lbs. and the gun they’d chosen was a heavy Colt 1911, weighing 41.7 oz. plus 9.25 more for the holster. But wait; it wasn’t just any Colt 1911.

A Special Gun

I knew it was a special gun after getting a brief look at it during a visit to Reecy’s home shortly after Joe’s death in 2011. It wasn’t until later I learned of the gun’s value as a limited production, very unique .22.

As far back as June 1913, the U.S. Military was attempting to develop a .22 caliber rimfire handgun for training. Those earlier designs used blowback operation and didn’t provide the training similarities to the .45 1911 the military desired. Colt had some success with them on the commercial market, but it wasn’t until David M. “Carbine” Williams designed a floating chamber, the WWII U.S. Army contract Model 1911A1 “Service Model” Ace pistol chambered in .22LR duplicated the weight, feel and function of the original Model 1911A1 pistol. Total production of Service Model Aces was only 13,800.

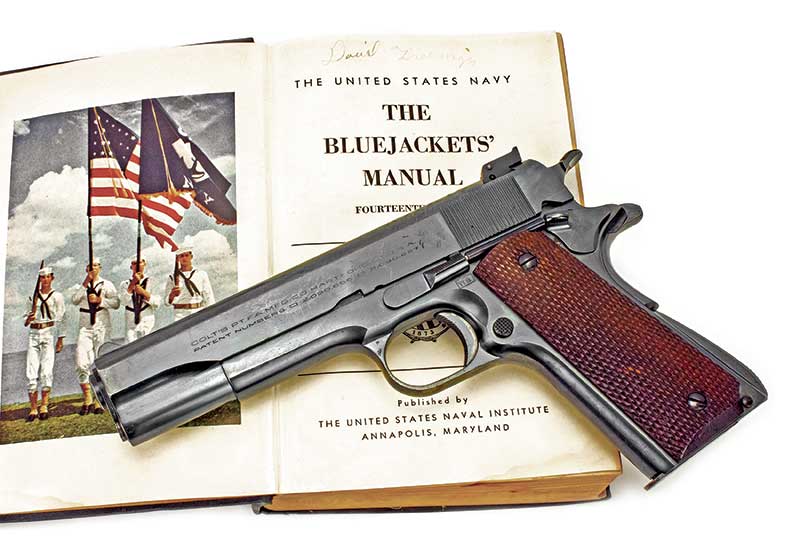

When I knew I would get the opportunity to handle, photograph and even shoot the Ace, I anticipated it might be in its original box along with the owner’s manual, perhaps even a receipt, but that wasn’t the case. It turns out Joe purchased it as a used gun. It’s in a GI holster and has a few minor scratches and a bit of pitting here and there.

I obtained a factory letter from Colt indicating this pistol was shipped to the Commanding General, Springfield Armory, Springfield, Mass., on December 16, 1941 in a lot of 60 guns, processed on Colt Factory Order #9966. It sure would be interesting to know how this military-owned gun was in civilian hands when Joe bought it five years later. It’s possible Joe picked the make and model because he had trained with one like it in the Navy. Then again, there weren’t a wide variety of handguns to choose from back in 1946.

Reecy’s pistol has a two-line Colt address with patent numbers on the left side of the slide with the Rampant Colt logo at the end of the markings. The right side of the slide is marked, “Colt Service Model ACE 22 Long Rifle.” The left side of the frame has a W.B. proof mark indicating the gun was inspected by Col. Waldemar Broberg, U.S. Army.

The ACE has an adjustable rear sight with target height front sight. The front strap is smooth, while the main spring housing is arched and covered with a checkered pattern. The hammer has a widened, checkered thumb pad and the trigger is curved and checkered. The grips are reinforced Colt wood grips with no markings or logo.

A Unique Design

The military desired a .22 training pistol that emulated the recoil of their larger .45 semi-automatic. Ammo cost was a major issue during wartime. The designer of the “Floating Chamber” which accomplished the desired goal was not a trained engineer working in a large manufacturing company but was a young man from the small town of Godwin, N.C., who worked out many of his design ideas while in prison.

After being released from the Navy for lying about his age, David Marshall Williams (“Marsh” to his friends) worked in a blacksmith shop while running a still on the side. During a raid on the still, Williams engaged the raiding officers with gunfire and killed a deputy sheriff. He was charged with first degree murder, which in North Carolina would have meant the death penalty, but they later changed the charge to second degree. Williams was sentenced to 30 years at the Caledonia State Prison Farm.

While serving his sentence, Williams spent hours sketching diagrams for various firearm mechanisms. As he gained the confidence of the prison superintendent, Williams was given access to the prison workshop where he spent his spare time repairing and maintaining equipment, including the guards’ rifles, and working on some of his firearm ideas. Friends and relatives campaigned to have the governor commute his sentence. These efforts proved successful, and Williams was granted parole in 1929 and released from prison in 1931.

Williams continued to refine his ideas and eventually filed four patents, including one for the floating chamber and one for the short gas stroke piston. Over his career, he worked at different times for Colt, Remington and Winchester and was responsible for several designs including the Colt ACE .22 and the M1 Carbine. Jimmy Stewart starred in the movie Carbine Williams, about David Williams’ life, making him somewhat of a legendary folk hero.

The floating chamber practically quadruples the recoil power of the .22 long rifle cartridge. The result is recoil that strongly reminds the user of the .45, though in fact it’s considerably less. It’s unnecessary to reduce the weight of the slide or the strength of the recoil or mainspring to build a reliable .22 on a 1911 frame.

When a Service Model Ace is fired, pressure on the front end of the floating chamber drives the chamber to the rear until a lug on the bottom strikes a corresponding lug on the barrel and stops the motion. As the floating chamber rests against the breech block, the motion is transmitted to the slide which is thrown to the rear against the action of the recoil spring, cocking the hammer and compressing the main spring.

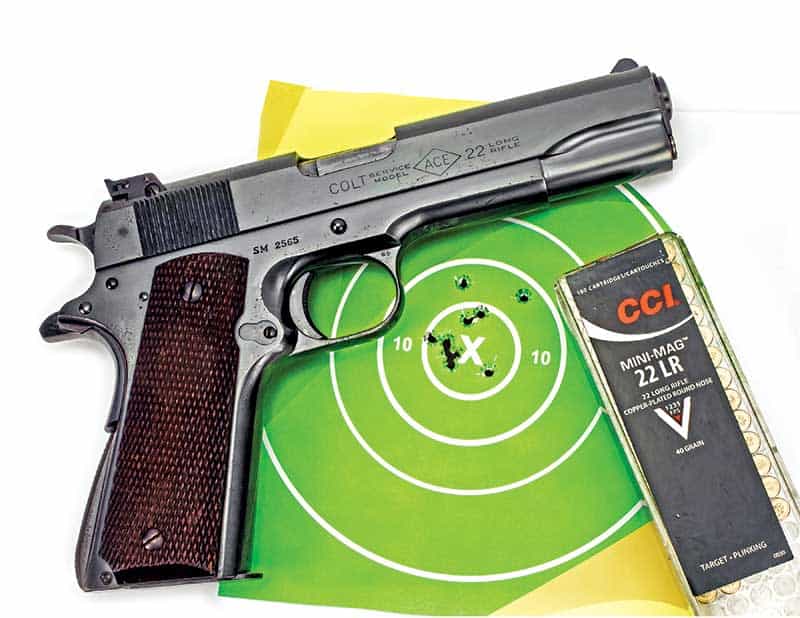

Does It Shoot Like A .45?

Since I have a much newer Colt .22 1911 made by Walther under contract, I figured it would be interesting to shoot the two pistols side by side for comparison. Ammunition for the mission consisted of 100 CCI Mini-Mag .22 Long Rifle cartridges. I shot 10 rounds in one gun, then 10 in the other, repetitively, until I ran out of ammo. I fired each 10-round magazine at a different target with the targets out at 10 yards.

Did the Ace feel much more like a .45? Not to me. I could see the muzzle flip, but I knew I was shooting a .22 the whole time. The Walther Colt’s muzzle flipped also, but it’s a lighter gun, weighing in at 36 oz. The trigger pull on both guns was similar at just over 5 lbs. I could have shot either all day except for the difficulty I had pulling the little button down against the spring to load .22 magazines. The Ace grouped inside of 3″ and the best inside of 1.5″. The Walther Colt grouped inside of 4″ across the board.

What an opportunity — to fire a unique WWII firearm and better yet, to know it’s in the family. Reecy has assured us it will be for perpetuity as the Ace has special memories for her of her husband’s love and concern for her safety.