For Want Of A Cavalry Colt

One Man's Quest For A Dream-Gun

For some unfathomable reason I’ve always had a deep interest in the history of the United States horse soldier, especially from the Indian Wars era of 1866 to 1890. In 1968 there were a few weeks between the end of my summer job and the beginning of my second year in college. While most of my contemporaries headed for places like Virginia Beach, Myrtle Beach, or points in Florida, I drove from West Virginia to Montana for the sole purpose of seeing what was then called the Custer Battlefield. Now politically correctly called Little Bighorn Battlefield.

While there I walked the ground above the Little Bighorn River to gain a sense of the fight, but when visiting the museum there happened a defining moment in my shooting life. On display were samples of the weapons used by both Indian warrior and cavalryman. Among the 7th cavalry’s items was what we call today a Colt Single Action Army .45 caliber revolver with 71⁄2″-barrel, onepiece walnut grips, and the (misnamed) black-powder frame. That particular display revolver was by no means in new condition. Instead it was covered with a dark brown patina as would befit a handgun nearly a century old that had been carried much in the outdoors. And I wanted one.

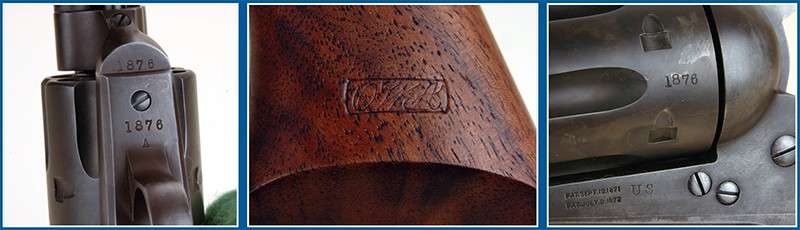

Top-left: Duke was lucky enough to get the serial number “1876” for his USFA Custer Battlefield .45.

The small “A” stands for Ainsworth, the government inspector at the Colt factory at the time the Custer Battle

single actions were manufactured. Middle: Ainsworth also stamped the walnut grips of each SAA

to leave the factory with his own personal cartouche.

Top-right: Note the U.S. stamp on the frame and the serial number also placed on the

cylinder. Both are authentic to Custer Battle era SAA revolvers.

Duke’s Itch

That wasn’t an easy itch to scratch. Colt introduced the Single Action Army and its .45 Colt cartridge in 1873 and the U.S. Army accepted it that same year for cavalry service. In fact, the 7th Cavalry’s 1874 summer expedition to explore the Black Hills area was delayed until the regiment’s new Colt revolvers arrived via railroad from the east. From 1873 until 1892 the Colt SAA .45 was standard issue for U.S. Army horse soldiers, and it actually remained in their hands for some time after the official adoption of a Colt double-action .38 revolver in the early 1890s. Many were returned to service for duty during the Spanish-American War and the Philippine Insurrection.

The standard Cavalry Colt SAAs were all of a theme. They were issued with 71⁄2″-barrels, one-piece walnut stocks, and color case hardened frame and hammer with the rest of the metal parts blued. Some finish variations are known to exist but in numbers so small as to be curiosities. It was a simple and rugged handgun as necessary for one intended for horseback carry. During that almost 20-year period when the U.S. Army was buying Colt .45 revolvers, the total numbers purchased were not large. According to A Study of the Colts Single Action Army Revolver by Graham, Kopec, & Moore the government bought only about 37,000 Colt .45s.

What makes original cavalry Colts even more scarce is the fact between 1895 and 1903 the Army rebuilt and altered MOST of the Colt .45s they had in storage. Their barrels were cut to 51⁄2″ and they were stripped down with the parts refinished or replaced as need be. Most were then reassembled from the refurbished parts with no attention to matching serial numbers. Today collectors commonly call these shortened cavalry Colts “Artillery Models,” but it should be stressed they were not issued only to artillery units after alteration.

The Quest

According to the book mentioned above, most of the Colt .45s that actually saw service with the horse cavalry were among those altered. Many that escaped alteration had been lost or stolen during service. For instance, in the debacle along the Little Bighorn River in 1876, the 7th Cavalry lost well over 200 SAAs to the Sioux and Cheyenne victors. Also quite often deserters took their revolvers with them. And too, it’s well documented that some troopers (making $13 a month) sold their new pattern sidearm to civilians at scalper prices of up to $50 and then gladly paid the Army the $13 or so they were docked for “losing” them.

Back to my quest for a U.S. Colt SAA. So impressed was I with Montana on that 1968 trip I returned every summer break to work there, and then became a permanent resident after graduation in 1972. During those youthful years a genuine Cavalry Colt was far out of my budget. So I determined to build a facsimile. In the spring of 1975 when visiting family back east I wandered into a gun store in Prestonsburg, Kentucky. That store had a rather ratty looking Colt SAA .38-40, but what attracted me to it was the fact that it had the black-powder frame, and the triggerguard was marked with a tiny “.44 CF”. That latter point told me that the gun wasn’t original, so I would do it no great harm by building it into my long desired Cavalry Colt.

Back in Montana I ordered a 71⁄2″ .45 Colt barrel and cylinder from Christy Gun Works of California, and then had a gunsmith install them in the old SAA frame. An atrocious-looking set of onepiece walnut grips were cobbled together for it, and I joyfully set about shooting my cavalry Colt — with light .45 Colt loads in deference to its old frame. My initial impression was, “Boy, this long barrel must make those loads shoot harder. This gun kicks!”

Regardless, it was accurate and I fired several hundred rounds through it. Then one day I decided to slug the barrel. The resulting slug measured .429″! I slugged it again with the same results. Christy Gun Works had sent me a .45 Colt cylinder but a .44 caliber barrel. To say I felt stupid about not noticing it was an understatement, but I took solace from the fact that my gunsmith hadn’t seen it either. Duh!

There’s Still Hope

In 1976 Colt introduced the Single Action Army for the third time, and since I had been working lots of overtime on a road maintenance crew in Yellowstone National Park, I ordered a .45 with 7″ barrel. What a disappointment! It was poorly finished and assembled so badly none of the seams where grip frame and main frame came together mated evenly. It’s trigger guard even came with a crack when new-in-box. I soon sold that .45. And duh again!

By 1984 I was a full time gunwriter and beginning to focus much of my attention on Colt SAAs, so I was aware Colt had improved quality somewhat and was also again offering the black-powder frame. However, this was a time when they would accept no orders for the SAA unless they came with rather costly “embellishments.” That meant the buyer had to spring for additional things like presentation boxes, engraving, ivory grips, etc. so I sprang.

My order was for a 71⁄2″-barreled .45 with fancy box and ivory grips. As soon as it arrived the ivory grips were stashed away and I had a gunsmith fit it with plain walnut one-piece stocks. He was even able to put a facsimile of an inspector’s cartouche on the left grip panel just as the original U.S. Colts had. I was fairly happy with that gun, and even carried it in 1986 on a horseback ride that traced the 7th Cavalry’s path from where they spent the night of June 24th/25th 1876 right up to the battle monument near where Custer’s body was found after the fight.

Still Not Right

However, I still wasn’t completely satisfied in my quest for a “Cavalry Colt.” Mine didn’t have the “U.S.” stamp on the left side of the frame, its hammer wasn’t color case-hardened, and its sights weren’t the old-style fine ones of early Colts. Surely, that was nitpicking, but I was getting more affluent and could afford to be picky. By that time I perhaps could have even bought an original Cavalry Colt but that would have wiped out my ever-stressed “gunmoney fund.” Besides, I was a shooter more than a collector and even then was smart enough to know doing much shooting with something as valuable as a genuine U.S. marked Colt SAA wasn’t real bright.

Back in 1975 Colt had brought out a limited run of what I felt would be the perfect “Cavalry Colt” for me. Those were the Peacemaker Centennials in .44-40 and .45 Colt calibers. The ones chambered for the latter round were precise duplicates of U.S. Cavalry issue Colt SAAs — right down to tiny details such as the sights, markings and grips. The only fly in the ointment was that as commemoratives they had the logo “1873-1973” on the right side of their barrels. I could live with that.

The problem was in finding one. Colt built only 2,002 of them so they weren’t just languishing on dealer’s shelves. Indeed once in the late 1970s I even saw one at a gun store, and drove the 80 miles home to gather money only to return to find someone else had already bought it.

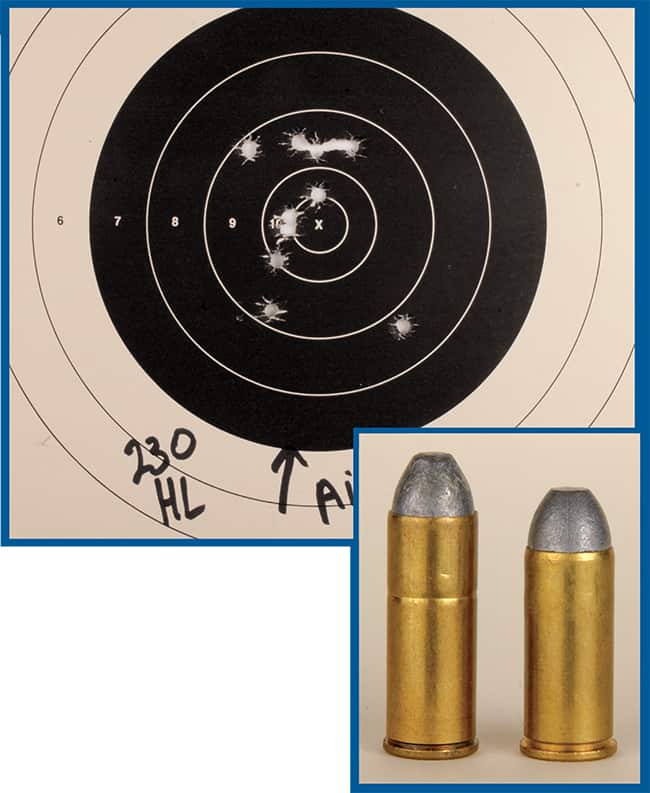

Above: Using Duke’s favorite .45 S&W handload his USFA Custer Battlefield revolver grouped

center at 25 yards with a six o’clock hold. Shooting was done from a standing position with one hand as was

taught to cavalrymen of the era. Right: Although the Colt Single Action Army handguns

shipped to the U.S. Army between 1873 and 1892 were chambered for the .45 Colt cartridge,

during most of its service life troops were issued with

the shorter .45 S&W “Schofield” cartridge.

Patience Wanes

Not until 1993 did I see another Peacemaker Centennial .45 for sale, and that was when a fellow walked up to my gun show table and set a brand new one down and said, “You interested in that?” Brother was I ever! Without quibbling I paid him his asking price, and after 25 years my Cavalry Colt itch was finally getting scratched. That big Colt .45 became one of my favorites; so much so it was one of the Colt revolvers shown on the cover of my first book, Shooting Colt Single Actions. I made such a fuss about it in print that in the year 2000 another fellow offered me a second one, so now I have a matched pair.

There’s More?

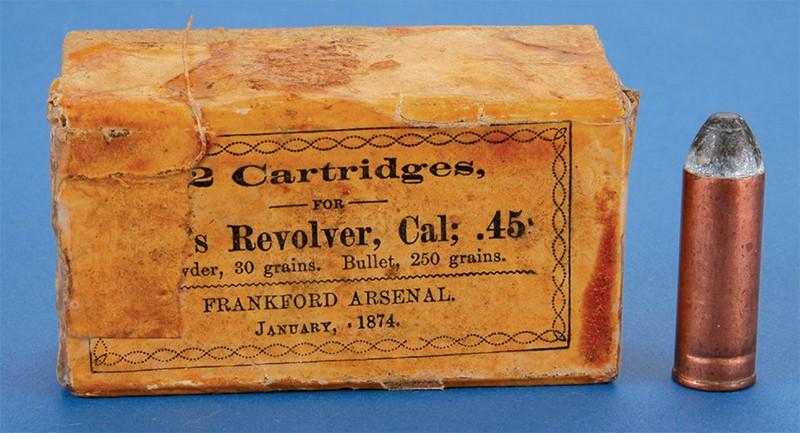

In cowboy-action matches I shoot them exclusively with black-powder loads, while doing my plinking and practicing at home with smokeless loads. Almost always I put those loads in .45 S&W “Schofield” brass, which is actually more authentic to the Indian Wars era than you might think. The Colt SAA was introduced in .45 Colt caliber, but by August 1874 the U.S. Army informed the government’s Frankford Arsenal to only build the shorter .45 S&W cartridge, which they did for the next 18 years.

Most cavalry units carried the shorter .45 S&W round in their SAAs, but modern archaeology has shown that Custer’s 7th Cavalrymen used the longer cartridges at the Little Bighorn. Anyway the difference in power wasn’t great. The government loaded the full-length .45s with 250-grain bullets over 30 grains of black powder. The shorter .45 S&W used 230-grain bullets and 28 grains of black powder.

At this point a normal person would be satisfied. But, what sort of “normal” person would become a gunwriter anyway? At SHOT Show 2005, I was visiting in the United States Firearms Manufacturing Company’s booth with their president, Doug Donnelly. My eyes fell on a Cavalry Colt in the display, and I had to ask, “Doug, what’s with that old Cavalry Colt mixed in with all your new guns?” His answer amazed me. “That’s one of ours” he said, “We’re offering a Custer Battlefield model, with antique finish.”

That did it. I ordered one on the spot, and in doing so I learned the buyer could even specify his own serial number as long as the number was in the range inspected by U.S. Army Ordnance Sub-Inspector Orville W. Ainsworth. That man inspected and stamped Colt SAAs at the factory in the era when they could have actually been issued to the 7th Cavalry prior to their fight at the Little Bighorn. Eagerly, I asked, “Has anyone taken the number 1876?” No they had not, and I got it!

At Last

A few days before this writing, my U.S. Firearms Custer Battlefield single action arrived. It’s all I had ever hoped for: the antique finish is dingy just like that original Colt SAA still on display at the battlefield’s museum. Sights, firing pin, ejector rod head and grips are perfect renditions of those items found on original “Cavalry Colts.” The “A” inspector’s stampings are precisely where they are supposed to be, as is the cartouche on the left side of the walnut grip, and the U.S. stamp on the frame’s left side.

Furthermore, it has that fantastic quality in regards to fit and lock-up the U.S. Firearms Company has gained such a positive reputation for. My only complaint about it is the bevels on the cylinder’s flutes are not quite as pronounced as with original 1870s vintage Colt SAAs.

Now at this point I’m supposed to describe just how tightly their test guns group. I’m not going to because I have never fired my USFA Custer Battlefield .45 for accuracy from a rest. There’s no reason since I intend to shoot it primarily as U.S. Cavalrymen did. That was with one hand because the other was needed for the horse’s reins.

Also it will almost always be fired with .45 S&W “Schofield” loads as most U.S. Colt SAAs were fired. Black Hills Ammunition makes a 230-grain .45 S&W factory load and I also handload 230-grain bullets in the .45 S&W cases over 5.3 grains of Hodgdon HP38. Both loads give about 730 to 750 fps from my USFA Custer Battlefield .45, and that’s precisely the power level given by original military loads. However, I should say that from 25 yards the USFA .45 prints groups about 4″ above point of aim and centered with my handloads, and about 2″ high and still centered with the Black Hills factory load. Remember that shooting was done from a one 2 handed standing position.

Interest in the horse cavalry of old has been a strong influence on my life. It even helped determine where I live and the types of guns I shoot. My onagain/off-again quest for a “Cavalry Colt” is over now, but it was sure fun during the nigh-on 40 years it lasted.

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: