Grandpa’s Top-Breaks

Carrying concealed is not a recent idea. All the “B” Western movies would have us believe everyone went around carrying openly; this was especially not true in cities. Yes, folks were armed, however they did it discreetly. The first viable cartridge firing revolver was the Smith & Wesson Tip-Up, 7-shot, single action chambered in .22 Short. Before this little pistol arrived both Colt and Remington produced .31 single action percussion pistols. All of these were fairly anemic by today’s standards but were certainly well above having nothing. Henry Deringer’s single shot percussion pistol became infamous when used by John Wilkes Booth.

The first successful center-fire cartridge firing revolver was the Smith & Wesson #3 American, which was chambered in .44 Smith & Wesson as well as .44 Rimfire to mate up with the Henry rifle. From the 1880’s well into the 20th century several firearms companies produced Top-Break pocket pistols. Top-break pistols are called that because they are hinged at the bottom-front of the frame and unlatch at the back-top of the frame, swinging down for loading and unloading.

Notable names include Iver Johnson, Harrington & Richardson and most assuredly Smith & Wesson. With today’s emphasis on safety triggers, internal locks and even padlocks, one might think this is a somewhat recent phenomenon. Not so, as the pocket pistols my grandfather had to choose from were often fitted with safety devices. My own grandfather had a .32 Iver Johnson Top-Break which eventually came to me.

Roy Jinks in his book History of Smith & Wesson traces the history of the Smith & Wesson early pocket pistols: “Within the Double Action group of revolvers, there is a series of pocket pistols that are unique in that they do not have an exposed hammer. They are truly just double-action revolvers rather than a combination of single and double action models like those previously discussed.”

Development

Legend has it D.B. Wesson developed the Safety Hammerless model in a night-long session after hearing that a child had accidentally been hurt by cocking and pulling the trigger on one of the Smith & Wesson Double Action Revolvers. This legend cannot be substantiated, since factory records show a methodical development of the revolver. D.B. Wesson was a sensitive person and perhaps after hearing of this accident was inspired to work very closely with his son Joe to develop a revolver with the safety on the handle and a strong trigger requiring a long pull, making it impractical for a child to pull through and fire.

The development of this style also stems from the law enforcement officer’s requirement to draw his revolver from his coat pocket without the exterior hammer catching in the pocket lining. The development of the handgun was given to Joe Wesson as one of his first projects while working at the draft board. Joe Wesson had much of his father’s inventiveness, and on February 15, 1882, he completed his first drawings for a .38 Hammerless revolver. This revolver is strictly a double-action revolver in which the hammer was completely enclosed by frame. The design also included a floating firing pin rather than a firing pin located on the hammer.

That first revolver design was not accepted by D.B. Wesson and subsequently, in 1884, Joe Wesson designed the .38 Safety Hammerless revolver which had a lever along the back of the grip strap. Unless this lever was pressed positively by the gripping hand, the hammer was blocked from moving. This design was finalized in 1886.

Roy Jinks says: “When the revolver was developed in 1886, plans were made to produce it in three calibers: .32 S&W, .38 S&W and .44 S&W Russian. In fact, the first advertisement stated the revolver was soon be produced in all of these calibers. After producing a prototype of the No. 3 Hammerless, as the .44 caliber model was called, all production plans were stopped and it was only produced in the other two calibers.”

The .38 Safety Hammerless would go through five models and over 250,000 revolvers from 1886 until 1940, with models available in barrel lengths from 2″ to 6″ as well as blue and nickel finishes. Two years after the arrival of the .38 Safety Hammerless, Smith & Wesson introduced a slightly smaller .32 Safety Hammerless and just under 250,000 were produced by 1937.

All of these revolvers are not only known as the Safety Hammerless Model but also as the New Departure. In addition to the Safety Hammerless version, Smith & Wesson also produced over 500,000 .38 Double Action Models with an exposed hammer, and nearly one-third of a million .32 Double Action Models. Adding up all the production figures of the Top-Break revolvers from Smith & Wesson shows just how prevalent Smith & Wesson revolvers actually were. And remember this was in the day before CCW permits, so it’s obvious thousands of people carried in grandfather’s time.

Iver Johnson

Smith & Wesson produced a lot of top-break revolvers, as did Iver Johnson. The Norwegian-born Johnson combined with a fellow by the name of Bye to form a company, however Johnson eventually bought his partner out and the Iver Johnson Arms & Cycle Works based in Massachusetts produced both bicycles and firearms. The original Johnson died in 1895 shortly after the arrival of the revolver with the strange name of “Safety Automatic.”

There was no safety and it certainly wasn’t a semi-auto. What it did have was an internal transfer bar safety. This was nearly 80 years before Ruger pioneered the modern transfer bar. Just as with the Ruger of today the transfer bar on the Iver Johnson rode between the hammer and the cartridge and prevented the gun from discharging unless the trigger was depressed all the way, at which time the transfer bar would retreat. If the trigger was not pressed there was no way the gun could fire.

Iver Johnson used this in their advertising to great effect. Large letters proclaimed “Hammer the Hammer” and the advertising pictured an Iver Johnson held in one hand and a carpenter’s hammer being used in the other hand to smack the hammer soundly. I can guarantee if this is tried with traditional Single Actions, such as the original Colt or early Rugers, the gun will definitely fire if there is a round under the hammer.

By the time Iver Johnson brought out their Safety Automatic Revolvers more than a few shooters had probably shot themselves or others because they dropped Colt Single Actions which were fully loaded with a round under the chamber. Elmer Keith wrote of one cowboy who hit the hammer of his holstered Colt Single Action with his stirrup and the gun fired.

Iver Johnson also proclaimed their “Safety Automatic Revolver is not a revolver for you to make temporarily safe by throwing on or off some lever, but a revolver that we have made permanently and automatically safe by the patented exclusive Iver Johnson construction.” The Iver Johnson Safety Automatic sold for $6-$7 depending upon the finish.

Trigger Safety

Just as with the Smith & Wesson Top-Breaks, the Iver Johnsons were chambered in 5-shot versions of .32 S&W and .38 S&W as well as a 7-shot .22 Long Rifle. Just as with Henry Deringer’s pocket pistol, Iver Johnson’s version became infamous when it was used by Leon Czolgosz to assassinate President William McKinley, causing Theodore Roosevelt to become president.

Okay, so the transfer bar is not a new design, having been pioneered by Iver Johnson so long ago. At least the safety trigger as first found on the Glock is new, right? Nope, no new design here either. Long before Gaston Glock was born or even thought about producing firearms, Iver Johnson’s top-break pocket pistol was being produced with that funny little bar in the center the trigger. These were hammerless models so there was no hammer to hammer, however the safety trigger precluded it being fired unless positively pressed. Iver Johnson did not stop there. Some of the revolvers will have what appears to be a trigger stop behind the trigger in the trigger guard. This is not a trigger stop but rather another safety and the revolver will not fire unless the back of the trigger presses this little bar positively.

Smith & Wesson and Iver Johnson produced millions of these small pocket revolvers so you can bet a lot of folks went around armed. However, they are not the only manufacturers filling the pockets of numerous grandpas and grandmothers’ purses.

Other Makers

Beginning in 1880 Harrington & Richardson started producing top-break revolvers. Just as with the other makers, they chambered them in the two predominant pocket pistol cartridges of the time, the .32 S&W and .38 S&W. One thing we haven’t mentioned is how quickly top-break revolvers can be unloaded and reloaded. When the lock is opened and the barrel turned 90 degrees down, cartridges, whether fired are not, automatically eject, and it’s very easy to then reload. Harrington & Richardson took advantage of this by calling their revolvers “Premier Auto Ejecting” and “Automatic Ejecting.”

Another company producing top-breaks was Forehand & Wadsworth. Diamond Dot has one in her collection of top breaks and it seems to be a quality revolver all the way around. A company that did not have a reputation for producing the best quality was Hopkins & Allen. What is most interesting about this company is they were hired to produce the Merwin & Hulbert revolvers, which were some of the best revolvers ever produced. Hopkins & Allen also produced many of the Forehand & Wadsworth revolvers.

All of the above-mentioned top-break revolvers are antiques, with some being nearly 125 years old. They were mostly chambered in two low-pressure cartridges like the .32 S&W and .38 S&W. Currently Buffalo Bore produces these two cartridges, and very emphatically states neither one of these is to be used in any top-break revolvers for several simple reasons. These guns were originally produced in the black powder era, of an inherently weak design. Buffalo Bore’s .32 and .38 S&W cartridges are for use only in solid frame Colts, such as the Bankers Special, and Smith & Wesson’s Terrier.

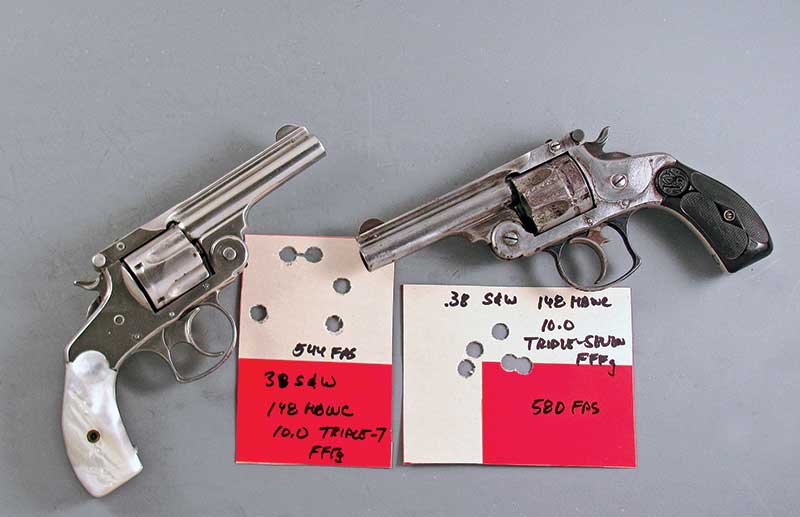

Top-break .32 and .38 S&W revolvers are currently being used in many side matches in Cowboy Action Shooting. If you happen to have one in excellent shape and wish to use it, please have a gunsmith check it first. You might also consider locating a chart of serial numbers which will shed light on which guns are black powder and which are intended for smokeless powder. I pretty much stay safe, using black powder loads in these old revolvers.