Killing Lincoln

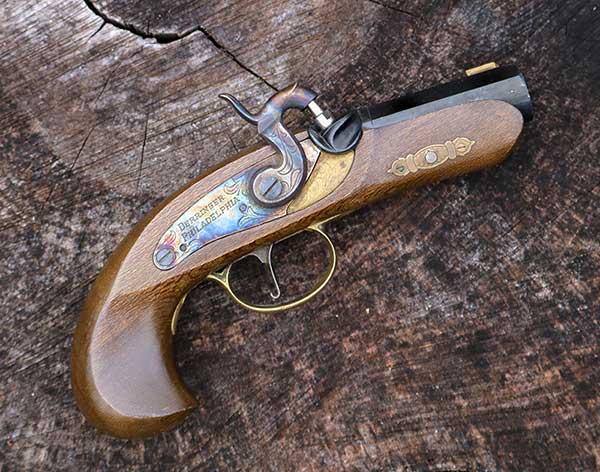

John Wilkes Booth’s Philadelphia Deringer

Is it just me, or does the American political landscape seem exceptionally acrimonious these days? One might be forgiven for thinking today’s schism between Left and Right so bellicose as to be without historical precedent. However, that’s not quite true. The vitriol back in 1865 made today’s political shenanigans look like a cordial Sunday School picnic.

The American Civil War was by far the costliest conflict in American history. Brother rose against brother, and places like Gettysburg, Shiloh, Chickamauga and Antietam were awash in blood. Nearly 620,000 Americans perished. Along the way, rancor in American politics reached levels not seen before or since. When folks get that fired up about something they tend to do stupid things.

The Players

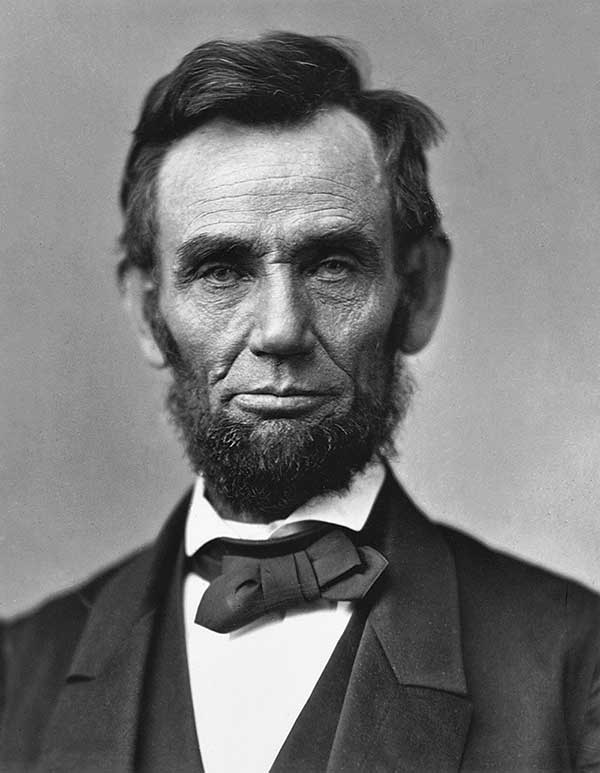

Abraham Lincoln was famously born in a log cabin in Kentucky in 1809 and was essentially self-educated. From these humble beginnings, he eventually ascended to the Presidency during the most tumultuous period in American history. Lincoln’s force of personality is what kept the Union together through four long, bloody years of war.

Lincoln’s personal life was fairly tragic. His wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, was mentally unhinged, and three of their four sons died young. The weight of having carried the Union through the Civil War exacted a profound toll.

At 6’4″, Lincoln was a veritable giant in his day. It has been postulated that he might have suffered from Marfan’s syndrome, a connective tissue disorder that generally leaves those afflicted extremely tall and thin.

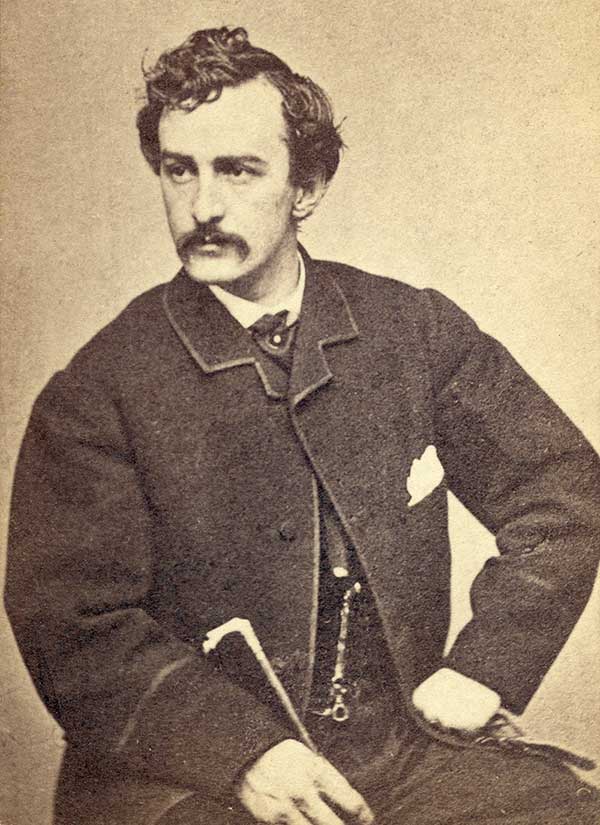

John Wilkes Booth was an accomplished actor and an old-school bigot. In the late 1850s, he was earning $20,000 per year, which is about $700,000 today. A rabid proponent of slavery, Booth fervently hoped the Confederacy would prevail. He saw Lincoln and his fellow Republicans as an existential threat to the sordid practice.

Theater critics extolled Booth as “the handsomest man in America” and a “natural genius.” One reporter described him as a “muscular, perfect man” with “curling hair, like a Corinthian capital.” Mix such unfettered adoration with a pinch of insanity and you have the recipe for some tragically bad behavior.

The Background

It was originally just supposed to have been a kidnapping. The idea was to abduct the sitting President of the United States and then exchange him for Confederate POWs. There wasn’t much of a plan past that. However, on April 9, 1965, General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox, and everything changed.

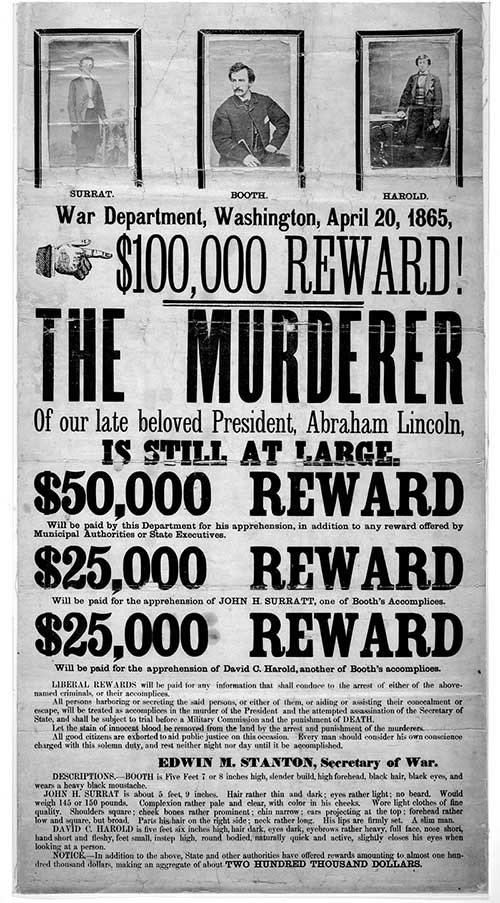

Booth still believed that a decapitation strike against the hated Union government might yet turn things around for the beleaguered Confederacy. As such, he and a few co-conspirators planned a simultaneous attack against Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward. Booth’s friend Lewis Powell stabbed Seward, though not lethally. Co-conspirator George Atzerodt got cold feet and spent the critical evening in a local pub rather than trying to assassinate the Vice President.

Booth’s fame as a thespian gained him unfettered access to Ford’s Theater during the showing of Our American Cousin on April 15th, 1865. Though Booth and Lincoln had never met, the President was well-acquainted with the famous actor, even going so far as to invite him to the White House on several occasions. Booth, for his part, forever declined.

On the fateful evening, the President and his wife were accompanied by Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée Clara Harris. General Grant and his wife had been invited but were unable to attend. The door to their private box was guarded by a local policeman named John Frederick Parker. During the play’s intermission, Parker stepped next door to a nearby tavern for a drink accompanied by Lincoln’s valet and coachman. This turned out to be a pretty significant decision.

The Hit

Booth knew the play by heart. He stood outside the President’s box and waited for a particularly uproarious bit knowing the audience of some 1,700 people would be laughing vigorously. He then quietly opened the door, stepped across the room, and shot President Lincoln in the back of the head with a single-shot caplock Deringer pistol.

The .44-caliber projectile entered Lincoln’s head behind his left ear, transited his brain, and flattened itself on the front of his skull after shattering the orbital structures along the way. Lincoln fell momentarily forward before spasming backward out of his chair. Major Rathbone then attempted to intervene. His tiny gun now empty, Booth stabbed the Federal officer twice for his trouble before leaping out of the box some 12 feet to the floor below. Booth injured his leg in the fall but nonetheless still made his way across the stage. The audience assumed this was all part of the production.

The Gun

Over the years, “Derringer” has become a proprietary eponym not unlike Kleenex, Band-Aid, Magic Marker, or Popsicle. Nowadays, all small single or double-barrel pocket pistols are called Derringers. However, the term has its origins with one Henry Deringer. Henry launched his single-shot Philadelphia Deringer pocket pistol in 1852, producing around 15,000 copies over 16 years.

The Deringer defensive pistol was phenomenally popular. As these were the days before meaningful copyright enforcement, everybody and their grandmother began producing copies all over the world. In many cases these knock-offs even had “Philadelphia Deringer” engraved across the side. Eventually, somebody somewhere added an extra “R” to Deringer’s name and “Derringer” became the new normal. Most of Henry Deringer’s original pistols sported rifled barrels and walnut stocks.

Trigger Time

I bought my Spanish-made .44-caliber copy of the Lincoln assassination gun for $86 in a small internet gun auction after a year-long search. As Booth killed Lincoln at contact range, accuracy really wasn’t a factor. The tiny little pistol pushes a 143-grain lead ball to around 250 feet per second when charged atop 25 grains of FFFG black powder. I used mine to shoot an eggplant, because I hate eggplant. The terminal effects were disappointingly tidy.

President Lincoln succumbed to his wounds the following morning. Booth successfully escaped but was cornered by Federal troops in a barn in King George County, Va., 11 days later. The Federals set fire to the barn and then shot Booth to death when he failed to surrender.

The authorities eventually arrested the theater owner, the guy who rented Booth a horse, some poor slob who had just been asked to mind Booth’s rental horse while he was indoors, and many others. All but eight were released. Of those eight, four of the conspirators were sentenced to death by hanging, including Mary Surratt, who owned the boarding house where Booth lived. These four were put to death eight days after they were convicted. The wheels of justice moved more quickly back then. Surratt was the first woman executed in United States history.

Major Rathbone never quite recovered from the trauma of that horrible evening. He eventually married Clara but then shot her to death in a fit of rage in 1883. He spent the rest of his days in an insane asylum. It all seemed a fittingly dark punctuation on the first successful assassination of a sitting U.S. President.