Sixguns To The Rescue

The M1917 In World War One

When America entered World War I in April 1918, the U.S. military found itself lacking in many areas, particularly in combat aircraft, tanks and machine guns. But when it came to handguns, American forces fielded the finest sidearm of the era, the .45 caliber M1911 auto pistol. Praise was heaped upon the massive Colt design, and deservedly so. From the very start of its service, demand for the M1911 was insatiable, extending to every branch of the armed forces. But Uncle Sam’s military planners could not foresee the production needs brought on by a World War. As the M1911 couldn’t be produced in the quantities required to meet the demands of the war’s timeline, U.S. Ordnance quickly pivoted to a tried-and-true American favorite: the revolver.

As luck would have it, S&W had recently produced a “New Century” heavy-frame revolver, chambered in .44 caliber for the U.S. civilian market, as well as nearly 70,000 chambered in .455 Webley for the British military. And while the rimless .45 ACP cartridge might have otherwise proved problematic for a revolver to extract, S&W offered a new three-round “half-moon clip” that made it all work out.

Half Moon Clips

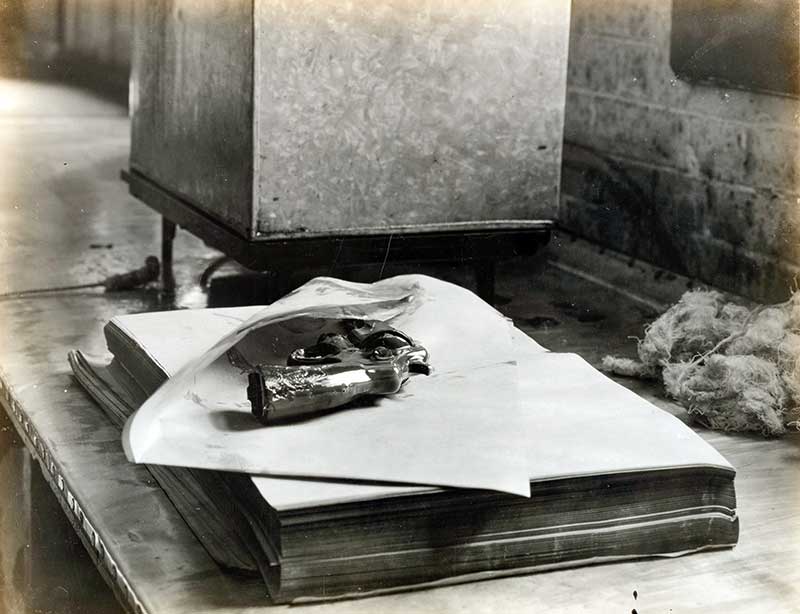

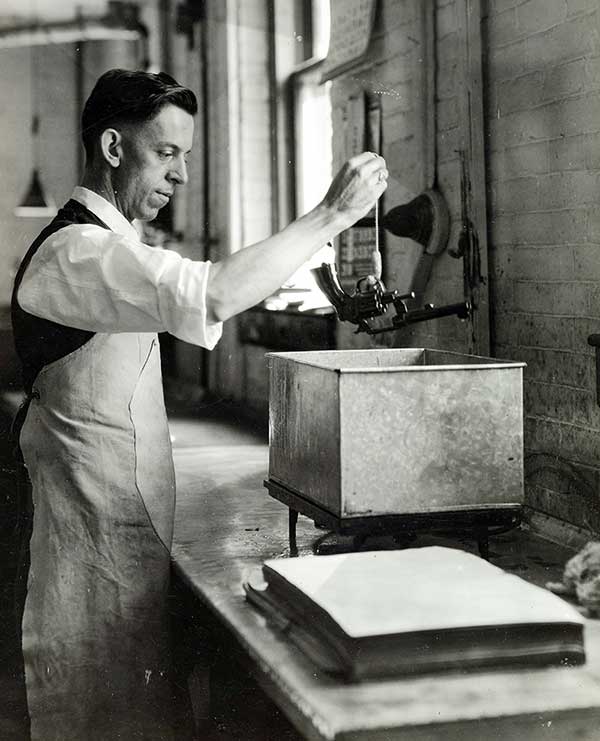

The M1917 revolver was designed to use the rimless .45 Government Automatic Pistol cartridge — at that time being made in large numbers for the M1911 pistol. While the use of the .45 ACP round eased logistical problems in one way, the rimless ammunition created a new challenge. Revolver cartridges usually have a rim that catches on the edge of the cylinder and allows the extractor to pull them out. The cartridges for an automatic pistol are usually rimless, so the rounds lay cleanly atop each other inside the magazine.

S&W developed a unique half-moon clip that allowed three .45 ACP cartridges to be loaded together. The steel clips lock the cartridges into the chambers securely, and with them, the M1917 revolvers can be loaded quickly, and the spent casings ejected easily. Without the clips, the .45 ACP rounds can be loaded one at a time, and unfortunately, they must be removed individually and with some difficulty — the empty cartridges needed to be pushed out manually with a pencil or dowel as the revolver’s ejector would not remove them.

Although Joseph Wesson patented the half-moon clip, S&W complied with a U.S. Army request and allowed Colt to use the clip design for free with their M1917 Revolver design. A big benefit of the clips in the early Colt M1917s was that the ammunition was properly seated and did not slip too far forward into the chamber. The S&W M1917 has a shoulder machined into its cylinder that allows the rimless cartridges to headspace properly.

A special three-pocket ammunition pouch, able to hold six half-moon clips, was issued in late 1917. Images of this pouch worn in the field are somewhat scarce, and it seems many Doughboys who carried the M1917 revolver improvised other ways to carry the clips.

The M1917 In Combat

More than 50% of American troops in France during 1918 were equipped with a handgun. Initially, the U.S. military intended that M1917 Revolvers would be carried by second-line and support troops, but the Doughboys’ enthusiasm for handguns meant ample numbers of the revolvers saw combat service. But while the M1917 Revolvers were important arms and issued in significant numbers (with a little more than 300,000 made in total), stories of their use in World War I are not common.

One reason for this is that the M1917 did not compare to the M1911 pistol in terms of popularity among the Doughboys, and consequently its use was not as widely celebrated. However, that does not mean the S&W and Colt .45 ACP revolvers were disliked — in fact, their ballistic performance and accuracy were essentially the equal of the M1911, and the weights of the revolvers and the auto pistol were close as well. If the Doughboys had disliked the revolvers or if the sixguns had not functioned well, we would have ample statements to that effect, and that is not the case. The relative quiet regarding the M1917 revolvers shows they did their job as a substitute for the M1911 well — the backup on a winning team is still a winner.

Meritorious Service

I did a little digging to find some stories of the M1917 revolvers in combat. What I found came from two U.S. Army Medal of Honor citations — offering ample evidence of the power of the M1917 revolver, and the qualities of the brave Americans who carried them.

First Lieutenant Woodfill: October 12, 1918 in the Meuse-Argonne region, near Cunel, with the 60th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division.

While First Lieutenant Woodfill was leading his company against the enemy, his line came under heavy machine gun fire, which threatened to hold up the advance. Followed by two soldiers at 25 yards, this officer went out ahead of his first line toward a machine gun nest and worked his way around the flank, leaving the two soldiers in front. When he got within 10 yards of the gun, it ceased firing, and four of the enemy appeared, three of whom were shot by Lt. Woodfill. The fourth, an officer, rushed at Lt. Woodfill, who attempted to club the officer with his rifle. After a hand-to-hand struggle, Lt. Woodfill killed the German officer with his pistol.

His company thereupon continued to advance until shortly afterward another machine gun nest was encountered. Calling on his men to follow, Lt. Woodfill rushed ahead in the face of heavy fire from the nest, and, when several of the enemy appeared above the nest, he shot them, capturing three other members of the crew and silencing the gun.

A few minutes later this officer, for the third time, demonstrated conspicuous daring by charging another machine gun, killing five men in one machine gun pit with his rifle. He then drew his revolver and started to jump into the pit when two other gunners, only a few yards away, turned their gun on him. Failing to kill them with his revolver he grabbed a pick lying nearby and killed both of them. Inspired by the exceptional courage displayed by this officer, his men pressed on to their objective under severe shell and machine gun fire.

Second Lieutenant J. Hunter Wickersham (deceased), 353rd Infantry, 89th Division: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty in action with the enemy near Limey, France, 12 September 1918.

Advancing with his platoon during the St. Mihiel Offensive, Lieutenant Wickersham was severely wounded in four places by a bursting high explosive shell. Before receiving any aid for himself he dressed the wounds of his orderly, who was wounded at the same time. He then ordered and accompanied the further advance of his platoon, although weakened by the loss of blood. His right hand and arm being disabled by wounds, he continued to fire his revolver with his left hand, until exhausted by the loss of blood, he fell and died.

Wickersham wrote a poem, The Raindrops on Your Old Tin Hat, the day before he died and posted it in a letter to his mother in Denver, Colo. It contained this verse:

“When you step off with the outfit to do your little bit,

You’re simply doing what you’re supposed to do,

And you don’t take time to figure what you gain or lose,

It’s the spirit of the game that brings you through.”