Old West Pistol Power

A Baffling Experience

A gunfight breaks out in a saloon, and one of the gunslingers up-ends a card table to fight from behind it. Bullets fly, usually from Colt Peacemakers, and hit the table — but fail to penetrate. I DON’T THINK SO!

Old West handguns may have fouled up quickly from blackpowder. They may have been slow to reload, and they may have had the most rudimentary of sights. But brothers, let me tell you something. They were nothing you’d want to hide behind a card table from, or a water trough, or a wagon box, or even a thin wooden wall. Someone would have shot you dead, neat as a pin.

Old West cartridges gave plenty of impact and penetration on the receiving end. Much of the real Old West happened before the advent of cartridge revolvers, so cap & ball types ruled for decades. Many of their users loaded them with simple round balls, which are about the lightest projectile you can have for any caliber. Still, they shouldn’t be ignored.

Duke Gets An Idea

Recently, while reading the book U.S. Firearms 1776-1875 by David F. Butler, I discovered some very interesting information. Butler says the U.S. Army’s 1874 Ordnance Manual listed ballistics for the .45 S&W cartridge as fired in the Colt Single Action Army revolver — which, incidentally, had just been adopted for cavalry service. That manual said the load launched a 230 grain bullet from a 7.5″ barrel at 730 fps, but that it would penetrate 3.5″ of white pine at 100 yards. Butler also said the Ordnance Manual notes that penetration of 1″ of white pine correlates to a dangerous wound.

It so happened my wife’s stepfather, Frank Eggers, was visiting us at the time, and no more handy fellow exists. So, I bounced off of him the idea of building a baffle box. The next morning he got to work, and the pleasing result was an easily-portable box taking replaceable 1×12″ white pine planks spaced 1″ apart. The boards are 18″ tall so that either the box can easily be hit from distance, or many different bullets can be spaced about it at closer ranges. Armed with that baffle box and my collection of both original and replica Old West revolvers, it was time for the fun to begin.

Baby Gun

Most of Sam Colt’s early revolvers like the Walker and various successions of Dragoons were behemoths. They weighed over four pounds and took powder charges rivaling the army’s rifle/muskets. Such handguns were meant for saddle holster carry, not tucking into your pocket. Early on, though, old Sam realized there was a huge civilian market for “pocket pistols.” In 1848 he brought out the Baby Dragoon, a .31 caliber, five shot revolver weighing only 22 ounces with 4″ barrel.

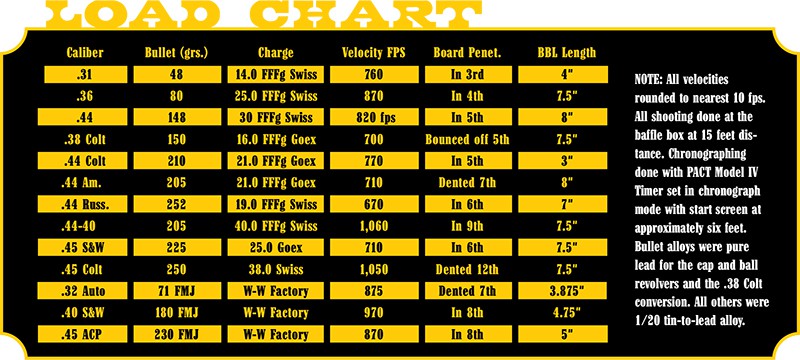

My guess is when the first frontiersmen looked at the 48 grain round ball and 14 grain powder charge normal for a Baby Dragoon they thought, “Give up my Bowie knife for that? Yeah, right.” But; the tiny .31 surprised us in actual tests. From 15 feet, that charge of Swiss FFFg blackpowder pushed the 48 grain .323″ diameter ball to 760 fps. It also lodged in the third pine board. Maybe, just maybe, a card table would stop that one, but I wouldn’t count on it. And neither should you.

Bigger is Better

Soon Sam Colt realized men needed more powerful revolvers, but ones still easily carried in belt holsters. Thus the “Navy” Colt was born. Today called the Model 1851, it used .36 caliber (actually .375″) pure lead bullets, which still only weighed 80 grains in round ball form. Powder charge was increased to 25 grains, which gave 870 fps. To our surprise, the .36 Navy only gave us one more board of penetration. Nevertheless, it served Wild Bill Hickock good enough in his several gunfights. Worth noting though is that Jesse James carried a .36 caliber ball in his torso for over 15 years with no apparent ill effects. Tough guy, that Jesse.

The epitome of the Colt cap & ball revolver was the Model 1860 Army, so named because the Federal government adopted it just before the outbreak of the Civil War. It used the same basic frame of the Colt Navy, but caliber was increased to .44, with powder charges running in the 30-35 grain range. A .457″ pure lead round ball weighs 148 grains, and the Swiss powder pushed it out of the 8″ barrel at 820 fps. It lodged neatly in the fifth pine board.

With the Colt Model 1860, easily portable handguns were getting what, even today, we’d consider adequate power. And just so you know, John Wesley Hardin favored a Colt .44 Army until the advent of cartridge guns.

Then What?

By 1870 metallic cartridges were becoming common. However, Colt had literally hundreds of thousands of cap & ball revolver parts on hand. Should they chuck them in the trash, or find a use for them? They were smart and figured out a way to build “conversions” of cap & ball revolvers. Essentially these “conversions” used cartridges based around the conical projectiles designed for the cap & balls, but carried in metallic cases.

They were either .38 or .44 caliber, with bullet weights of 150 and 210 grains respectively, and muzzle velocity for both was in the 700 to 750 fps range. It’s interesting to note the .38 Colt eventually evolved into the .38 Long Colt, which was considered a dismal failure as the U.S. Army’s handgun cartridge some years later.

Converting the .36 and .44 caliber cap and ball guns into cartridge firing revolvers didn’t make them significantly more powerful. The 150 grain .38 Colt bullet bounced off the fifth board in our tests. The 210 grain .44 Colt bullet lodged in the fifth board, but in all fairness it should be pointed out it was fired from a 3″ barrel, whereas the .44 cap and ball’s barrel had been 8″ long. What’s up with the 3″-barreled Colt conversion? In the 1880s, El Paso city marshall Dallas Stoudenmire carried one in a leather-lined hip pocket. I had a modern day gunsmith build one just like it. Just because.

High-Tech

Smith & Wesson pioneered the use of metallic cartridges, and by 1870 they had developed their Model #3, initially introduced chambered for the .44 Henry Rimfire. The U.S. Army told them some contracts might be forthcoming if they altered the ignition system to centerfire. They did this with little other change to the cartridge. Eventually the round gained the name “.44 American.”

The government was as good as their word and bought 1,000 S&W Model #3s with 8″ barrels. They were issued to cavalry regiments around the frontier, and saw much service. In fact, modern archeology has proven that no less than four Smith & Wesson Model #3s in .44/100 caliber were fired during the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

The Russians liked S&W’s new revolver, but not its cartridge. They redesigned it, and then proceeded to order hundreds of thousands of revolvers chambered for it during the 1870s. As things turned out the Russian design was superior to S&W’s, and the .44 American was soon dropped. The .44 S&W Russian cartridge became the father of the .44 S&W Special and the grandfather to the .44 Remington Magnum.

According to a Winchester catalog dated 1899, they loaded the .44 American round with a 205 grain bullet over 25 grains of blackpowder, and the .44 Russian with 255 grain bullet over 23 grains of the same. Modern manufactured brass does not hold that much blackpowder, but by using FFFg instead of FFg granulation I was able to duplicate the original velocities of those two cartridges. My 252 grain .44 Russian bullet lodged in the sixth board, while the 208 grain .44 American bullet dented the seventh. Maybe they were small, but those two cartridges packed some punch.

The Big Boys

By packing a .44-40 case full of Swiss FFFg and cramming in a 205 grain bullet, I about duplicated the original Winchester factory load, and even surpassed it a bit. It consisted of a 40 grain charge with a 200 grain bullet. Also, by scrounging through my old brass stash, I came up with 10 .45 Colt balloon-head cases. They easily held the 38 grain charge Winchester used in 1899 with 250 grain bullets. I included the fine old .45 S&W cartridge too. It was loaded with 25 grains of Goex FFg with a 225 grain bullet.

Now the fun part. With a muzzle velocity of 710 fps, the .45 S&W bullet lodged in the sixth board, giving it almost identical penetration with those other S&W cartridges, the .44 American and .44 Russian. When Jesse James was killed, he supposedly was wearing a S&W Schofield revolver and supposedly Bob Ford killed him with a shot to the head with a S&W .44 Russian.

But it was the .44-40 and .45 Colt cartridges that amazed us. The former hit 1,060 fps from a 7.5″ barrel, and the latter 1,050 from the same length. When they were touched off, you truly felt like there was a thunderstick in your hand! The 205 grain .44-40 bullet lodged in the ninth board, and the 250 grain .45 Colt one put a severe dent in board #12. Board 12, mind you!

Gunhands of the Old West wanted manstoppers. Little wonder then at the famous OK Corral shootout, it’s known Billy Clanton was packing a Colt Frontier Six Shooter (.44-40) and the Earps and Doc Holliday had Colt .45s.

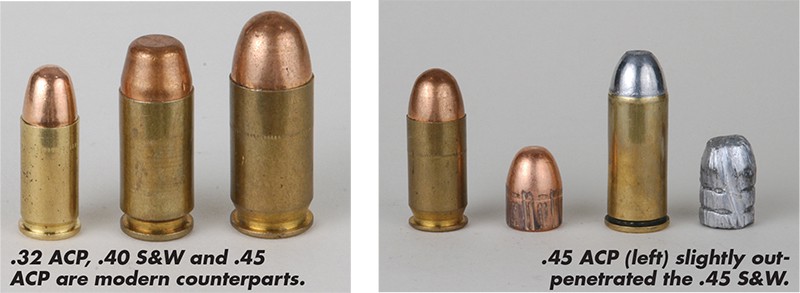

Old Vs. New

Wondering just how smug we should be with our modern technology, we shot some “new” cartridges too. A 71 grain FMJ .32 Auto bullet from a Walther PP severely dented the seventh board. A 180 grain FMJ from a Kimber 1911 Pro Carry lodged in board number eight, as did a 230 grain FMJ from a Colt 1911A1. They beat most of the old timers by a bit — but only a bit. And they can’t hold a candle to those .44-40 and .45 Colt beasts!

So here’s another old movie scenario: The bad guy gets the drop on the town sheriff, but his life is saved because a bullet imbedded in his tin star. If the bad guy had any sort of sixgun at all … I DON’T THINK SO!

If you’re wondering about the specifics of the handguns we used, wait no more. The three cap & ball revolvers are 2nd Generation Colts, dropped from the Colt line circa 1982. The conversions are based on the same 2nd Generation Colts with the work done by modern gunsmiths. For a .44 Russian revolver Navy Arms 3rd Model was used, but an original .44 American was pulled from my collection for that cartridge. The .44-40, .45 S&W, and .45 Colt loads were fired from Colt 1873/1973 Peacemaker Centennial commemoratives, which exactly duplicate 1870s SAAs.

The process of loading all those obsolete cartridges is too detailed to include in these pages. For specifics I’d like to refer you to my books Shooting Colt Single Actions and Shooting Sixugns Of The Old West.

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: