Cylinder Savvy

I’ve always been confounded by shooters who chase velocity, pressure and “power” in handgun calibers. If you’re developing a new cartridge, then indeed there are experiments to be made. Just ask Elmer Keith as he blew up old Colt single actions working toward the .44 Magnum. But for established cartridges like the .38 Special, .357, .44 Magnum, etc., virtually any standard velocity factory load will do whatever job needing doing. I’ve shot completely through deer, front to back, with a standard velocity hard cast .44 Magnum load. Why do we need more?

I hear comments like, “Well, that additional 65 FPS may make all the difference!” Difference in what? And what price tag does that additional velocity come attached to? I see people pushing their .38 loads into .357 territory, and their .357s into who-knows-where territory. Ditto for .44 Magnums, .45 Colts and even smaller calibers like the .32-20 or .32 H&R Magnum. They’re always chasing some ultimate happy place for them where they finally think “Oh, I’ve arrived.” Arrived where? Revolver cylinders are only “so” strong and are built to accommodate pressures as specified for the calibers they’re chambered in. It’s not good to play with Mother Nature.

A .500 S&W Magnum can handle 50,000 PSI, for instance. A .357 Magnum can safely handle 35,000 PSI, while the friendly .38 Special peaks at 18,000 PSI. The list goes on, of course. But what happens if you push that boundary? We’ve all seen photos of — or have experienced — a revolver cylinder letting go. What’s behind that and why does it happen? While there are a few good reasons you can get a “blowed-up” gun, let’s tell a short story first.

A Pressure Saga

I’m friends with a gent who spent some 25-odd years working for a big gun company who mostly made revolvers when he was there. He was hands-on, designing, building, doing quality control — the works. I brought up the concerns I have with people loading their revolvers too hot in pursuit of some velocity nirvana. He laughed and said, “If only they would think about those pesky cylinder bolt notches in their cylinders. In most guns, that cut is made right where a chamber rests, effectively cutting the chamber wall thickness there in half.”

In half?

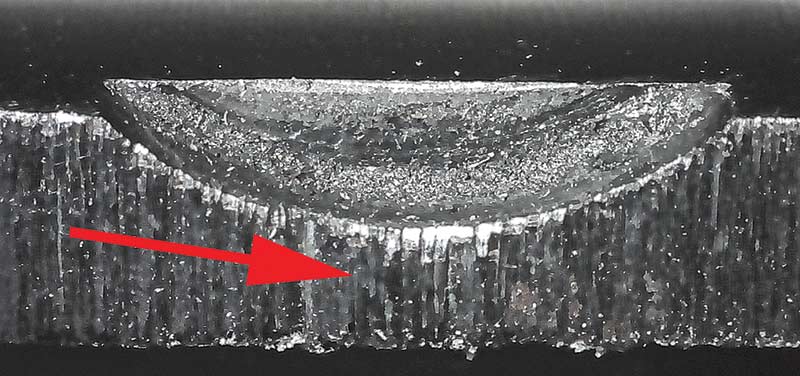

“I’ve seen revolvers where that bit of steel at the bottom of the bolt cut-out is pushed out, convex, due to pressure from a proof round. And the amazing thing is that means it met specs for that gun.”

It’s a fine line we stride between “safe” and “scary” when it comes to revolvers, and astute regard for load data is critical.

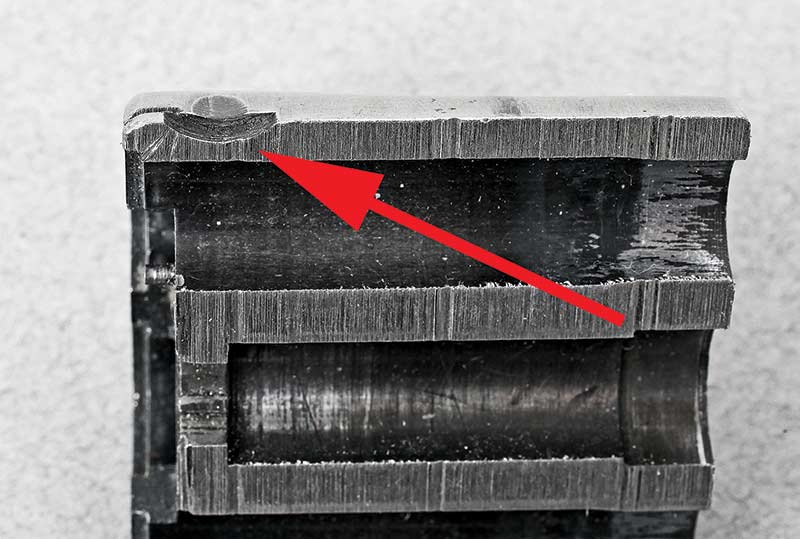

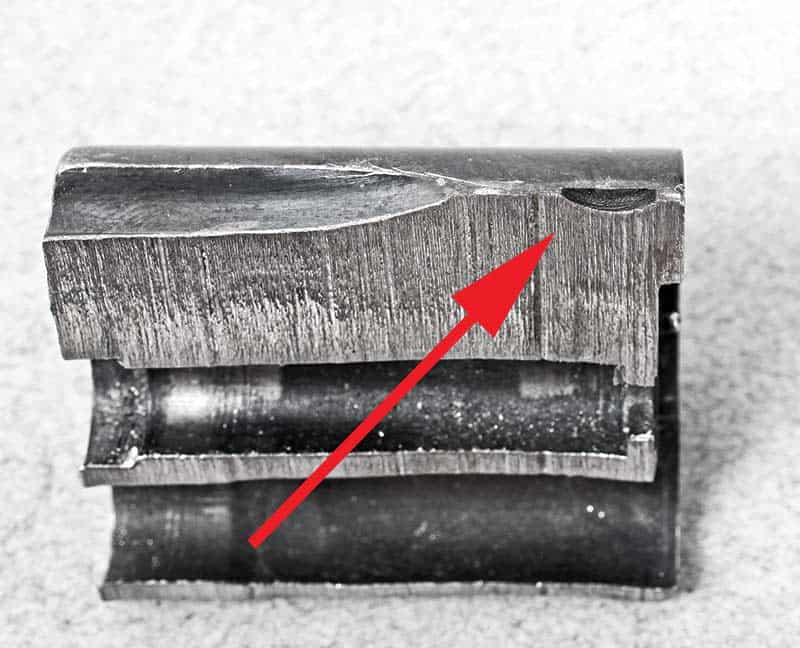

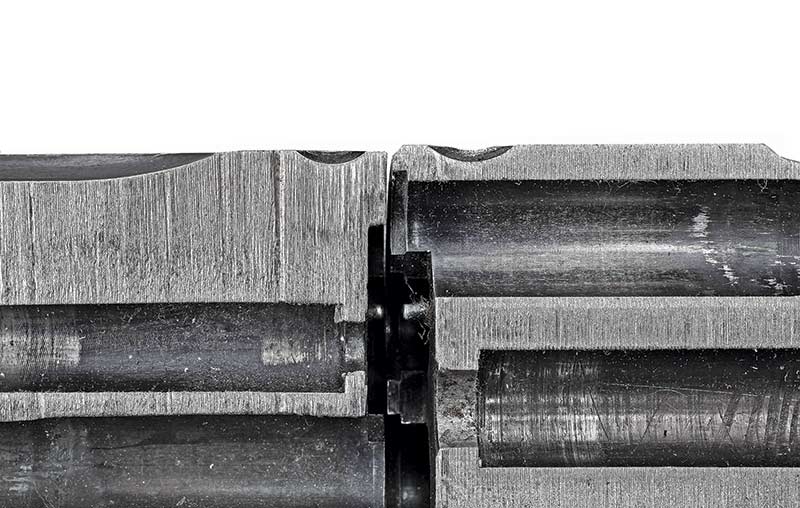

So, to prove this point, I took an old J-Frame cylinder and an N-Frame cylinder I had I normally use to set up fixtures or tooling, and simply sawed them in two, right at the cylinder bolt cut-out points. Keep in mind the 6-shot N-Frame’s bolt cuts were right at the chamber points, while the 5-shot J-Frame enabled the bolt cuts to be in the steel between the chambers. Check out the photos.

Note the normal cylinder wall thickness on the N-Frame and the thinner section at the bolt cut. Thickness runs from 0.120″ next to the bolt cut (full cylinder wall thickness) to 0.055″ at the cut — essentially half the thickness, right where the pressure happens. The J-Frame is unaffected by the bolt cut, but you still have to behave when it comes to pressure since the cylinder walls at the chamber are still at factory specs and able to handle factory specified pressures.

Some Back Story

In 1917 the Model 1917 S&W .45 ACP revolver was the first to have a heat-treated cylinder. By 1920, heat treating was introduced on all the current models of the time. By 1945 new steels were developed, enabling S&W to stop having to heat-treat the cylinders. You can shoot standard velocity .38 Special loads, for instance, in all the old .38 special guns, but stay away from +P and high-performance modern ammo. The heat-treating allowed guns like the 38/44 to be introduced, leading to the .357, which had a heat-treated cylinder.

Here’s a bit from a letter by D.B. Wesson (his great grandson, not the original DB), dated 1934, when responding to a customer letter asking about revolver cylinder strength:

“As a matter of fact, even in our larger calibers the steel as it comes from the mill shows a tensile strength in the neighborhood of 80,000 pounds, which does not make the additional strength gained by heat treating a necessity.”

Before everyone started using stainless steel alloys today, most “gun steel” was and still is 4140 series. Interestingly enough, most guns aren’t hardened the way people think they are. For instance, I’ve heard Ruger tends toward Rockwell 35 (RC35) for their barrels and cylinders. For comparison, a good knife blade might be in the high 50s. Most other makers tend toward the 20 to 25RC range. I have also heard from techs that many (most) revolver frames won’t even rate on the Rockwell “C” scale but will show up on the B-scale.

It’s complicated to harden, then treat steel so it’s not just hard (which means it’s brittle) but also “tough” to withstand pressure. Most modern steels used in gun-making come from the supplier already hard and tough enough to do the job without additional treating needed. There are exceptions of course, but generally, the steel is plenty able to handle the pressures the cartridges are rated at.

I hope as you look at those thin cylinder walls under the bolt cuts it makes you think hard before you increase the next load “just a tad” to chase another 100 FPS. I honestly can’t think of a time when an additional 50 or 100 FPS would make a significant difference in a bullet fired from a handgun, unless it was so slow as to be ineffective to begin with.

I always enjoy getting my hands dirty learning about stuff like this and I hope you learned a thing or two — just like I did.