Hi-Power Hi-Jinks:

Is It Like A 1911?

When Springfield Armory introduced their SR-35 late in 2020 you’d have thought it was the second coming of something. Well, I guess it was actually. Browning had nixed the design some years before, and shooters were hungry for a high quality example of the same ever since. Smart marketers they are, Springfield delivered the goods and promptly sold out — and I’ll assume they are pretty much still selling out.

But why do we care so much about this 80-odd-year-old design? One reason is because John Browning did the basic design work on it. I do wonder had he not been involved at all would the Hi-Power just be yet another in a long series of now defunct military pistols? Who knows? Nonetheless, if you peer at the design under a microscope and try to remain honestly objective, it does have a couple of interesting points.

First off, it’s pretty much not like a 1911 at all. It’s single action, has some of those barrel locking lug things, a thumb safety and loads with a magazine, but things pretty much stop there. Besides, hundreds of other designs have all those bits too. While people dearly love the Hi-Power, I think many (most?) of those who also shoot 1911-style guns just sort of leave their minds blank when it comes to honestly understanding how a Hi-Power functions. You load it, aim it, pull the trigger, “then a miracle occurs” and the gun fires and loads another. Repeat as needed.

But what’s really occurring as you pull that trigger?

Right off the bat, the trigger system is entirely different from a 1911. The 1911 uses a trigger connected to a stirrup wrapping around the magazine. That stirrup then bears on the sear, ultimately. When the trigger is pressed, it moves this stirrup to the rear, tripping the sear. There’s lots else going on too, but that’s the gist.

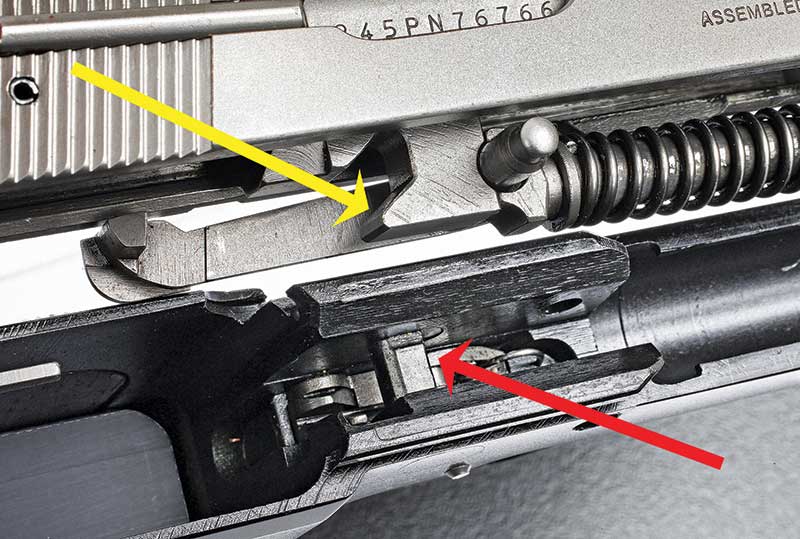

In the Hi-Power’s case, it gets more complicated. Put your thinking cap on and stare at the photos while we talk.

We’re looking at the frame (top) and the underside of the slide. To fire, you press the trigger,

moving the trigger lever (red arrow) up, pressing against the end of the sear lever (yellow)

in the underside of the slide. The lever pivots pushing the opposite end (blue) against the

nub on the sear (green) pushing it out of engagement with the hammer — firing the gun. Lots going on there!

The Hi-Power’s Action

There’s no grip safety on an HP, so there’s no way a trigger stirrup can slide out the rear. Nix that idea. So when you press the trigger (which, by the way, pivots on a pin at the top, also different from a 1911), that action raises a small bar (trigger lever) up, eventually pushing against the sear lever (which is in the underside of the slide). The sear lever pivots upward, causing the other end (toward the rear of the slide) to push down back toward the frame. A little nub on the lever presses against a corresponding spot on the sear (holding the hammer back), and if you keep pressing the trigger, it will eventually push the sear “off” allowing the gun to fire. It’s all a bit like a “knee bone is connected to the thigh bone” situation. I warned you this was going to hurt some to understand.

To top things off, there’s an additional small spring and plunger arrangement behind the trigger working with the magazine to allow the gun to fire if the mag is inserted, but not if it’s out. Oh, and there’s also a firing pin block tied into the top side of the sear lever on some models. When you press the trigger, moving the sear lever down, that moves the block allowing the firing pin to move forward when struck by the hammer. All of these bits rub and move against each other and any tiny glitch in fit, finish, polish, etc. causes a scratchy, gritty and heavy trigger pull. This is why Hi-Powers have always been known to have triggers more akin to dragging your boot across a gravel driveway than the “clean break” of a sear.

Springfield’s SA-35 does away with the magazine safety and the firing pin block, helping to smooth things out right off the bat. They also take care, assuring the bearing surfaces are well attended to. In my tests with a stock SA-35, I found the trigger press to be about like those in my custom Hi-Powers — which are good. No gravel driveways present.

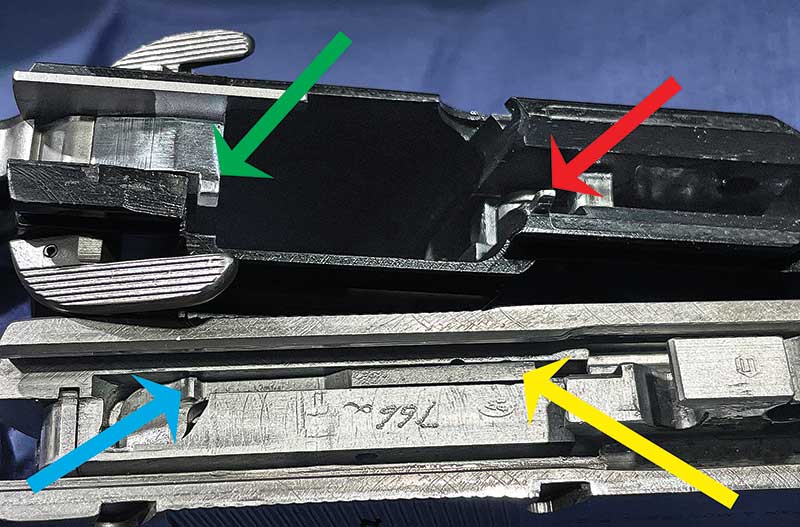

A 1911 frame (lower) and barrel showing the swinging link (red arrow). The slide release

cross pin (yellow) goes through the hole in the link, pulling (camming) the barrel out of the

slide locking lugs after firing. It also forces the barrel back into those lugs as the slide returns

to battery. Browning got rid of the swinging link and the link pin on the Hi-Power. Smart fellow.

Barrel Locking

Another key difference is the 1911 uses the famous “swinging link” held by the slide release cross-pin. After firing, as the slide moves back the barrel remains locked for a short distance, allowing pressure to lower. Then the link “pulls” the barrel down and out of the locking recesses in the slide. The slide continues back ejecting the empty, then slams forward due to the recoil spring, picking up the next round. As the slide goes home, that same link forces the barrel up and back into the locking lug recesses.

On the Hi-Power, the swinging link is gone. There’s a metal camming surface built into the frame just above the trigger location. Note in the photo, there’s a cam on the bottom of the barrel but the slide release cross-pin isn’t involved with it. After firing, the slide moves back with the barrel captured as in the 1911; however, at meeting the camming surface in the frame, the barrel is pulled down out of the locking lug recesses. The slide does the eject-and-load thing, and as the slide moves forward, the barrel is cammed back up into the lugs. A touch of Browning here is the fact he got rid of two moving parts (the 1911 swinging link and link pin).

If you’re having trouble getting a feel for this, jump onto YouTube and find one of those slow-motion animated videos of the innards of a 1911 and a Hi-Power. It’ll really help put things in perspective. In the meantime, keep staring at the pics and holding imaginary guns up in the air in front of you while you talk to yourself and ponder on it all. You might also do it when you’re alone in the garage so people don’t point and stare.

Feel free to drop us a note at [email protected] if you have questions or would like to see something specific in this series on understanding how things work.

For info: Springfield-Armory.com; Cylinder-Slide.com