Safe Carry Modes

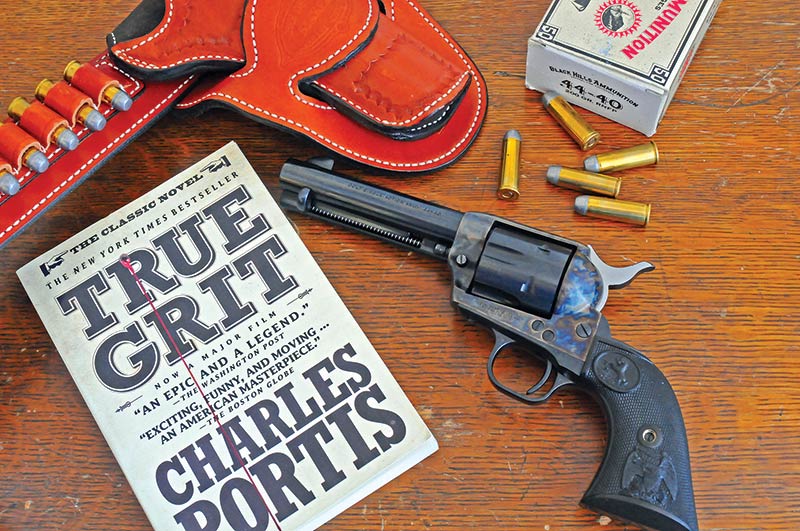

The Colt Single Action Army was introduced in 1873 and with only occasional breaks has been in production to the present day. Throughout the nearly 150 years of its existence, it’s been common knowledge to keep an empty chamber under the hammer whenever the revolver is loaded.

The firing pin of the Colt SAA attaches to the hammer. If there’s a live cartridge in the chamber under the hammer, the firing pin is pressing on the primer. A blow to the hammer spur can cause the cartridge to fire. And no, keeping the hammer in the “safety notch” is not an option. The purpose of the safety notch is (we hope!) to catch the hammer should it slip while being cocked. The interface between the notch and the thin tip of the sear is not very robust. A brisk blow to the hammer spur will almost certainly cause the revolver to fire.

This is hardly breaking news. The rule “five beans in the wheel” is as old as the revolver. When loading a traditional single action Colt or similar revolver, open the loading gate and bring the hammer to the third (loading) notch, which frees the cylinder to rotate. Load one chamber, skip one, load four, bring the hammer to full cock and carefully lower it on the empty chamber.

The 1911

The popular 1911 has two ready modes. Most shooters who carry one use the cocked-and-locked mode — full magazine, cartridge in the chamber, hammer at full cock and manual safety engaged. With most modern 1911 designs the beavertail grip safety curls around the hammer to protect it from impact. Even the original short tang grip safety did a fairly good job of shielding the hammer.

Some shooters simply cannot feel comfortable carrying a 1911 cocked, even if firing it requires releasing two safeties and pressing the trigger. One solution is a holster with a thumb break or safety strap blocking the hammer. If the shooter still doesn’t feel comfortable carrying cocked and locked, a single-action semi auto may not be the right choice, and these days there are many options.

The second acceptable mode of carry is magazine loaded, chamber empty. With no round in the chamber the gun cannot shoot, no matter if it’s dropped, struck, or tossed into a fire. Magazine loaded/chamber empty is how I carry a hunting firearm in the field. The small amount of time taken to chamber a round has never cost me a shot yet, and if it does and the game gets away, no big deal.

Personal defense is a different issue. We carry a firearm to defend our lives against a sudden and unexpected lethal attack. Maybe there will be time to get the gun out and a round chambered — but maybe not. I won’t say this mode is really a bad idea. With practice, racking the slide to chamber a round can be done very quickly. At best it’s not as fast as cocked and locked; it takes two hands; and there’s the chance of a misfeed. Some very qualified people prefer to carry chamber-empty, and although it’s not my choice I won’t criticize.

A Bad Choice

Athird mode I used to see recommended for the 1911 is one I disapprove of thoroughly — magazine loaded, round in the chamber, hammer down or in the half-cock notch. Don’t do it. It’s only marginally faster than carrying with a chamber empty, while it greatly increases the risk of a negligent discharge. The lowered hammer is much more exposed to impact than when it’s fully cocked. In some models, a brisk blow to the hammer (like being dropped), combined with a weak firing pin spring and/or sensitive primer can result in the pistol firing.

Lowering and cocking the hammer manually carries the risk of having the hammer slip from under the thumb. We all think it will never happen to us. Well, it only has to happen once. As the saying goes any vessel carried to the well often enough is bound to get broken.

Lowering the hammer on a live round means both safeties are disengaged and the trigger is pressed — which are the things we do to fire the pistol. When thumb cocking, odds are the pistol will fire if the thumb should slip with the hammer just short of the half-cock notch (or if the notch fails to hold).

Hammer down on a live cartridge introduces a substantial degree of risk while giving very little in return. With cocked and locked, or empty chamber carry, there’s never a need to lower or cock the hammer over a live round. In fact there’s hardly any need to touch the hammer at all. Keep in mind these same ideas apply to the Browning Hi Power too.