The Art of Reviewing a

Semi-Auto Pistol

Reviewing guns is 38% objective, 54% subjective, and 93% opinion. Those of you who aced Trigonometry might have figured out we blew right past the 100% limit, but that just goes to show that evaluating a gun isn’t an entirely quantifiable exercise. Now that I think about it, there is a word for a perfectly objective gun review. Specifications.

You might have noticed we rarely regurgitate spec sheets around here. You’ll find few data tables or lists highlighting such obscura as the weight of a half-loaded magazine when affected by the gravitational influence of a shooting berm. Instead, we try to tell the story of a gun that fills in gaps not relatable by feature lists. How does it feel? Is it easy to shoot accurately? Does it work with a random collection of ammo recovered from the floorboards of your truck? But more than anything, our writers aim to convey the experience of their time spent with a given handgun. That’s the stuff you don’t get in factory brochures.

Here are just a few items from my mental checklist. Heck, some of these are things you can evaluate right in the gun store.

Fit And Finish

There’s an old saying that exposes some harsh reality in our character. “You are what you do when no one is looking.” A similar concept applies to examining a handgun.

Consider those non-contact areas in a pistol or revolver and take a look at the level of fit, finish, and, sometimes, polish. Do you see burrs, gouges or other heavy machining marks? To be fair, there’s little need for detail perfection in non-critical or visible areas. However, it’s a pleasant surprise (and bonus points) when a gun manufacturer makes the effort to finish those areas where no one is looking.

Of course, overall fit and finish is always story worthy and rarely are reflected properly on the specifications page. How does wood meet metal? Are moving parts flush when in their resting positions?

I always inspect the muzzle crown carefully for burrs or machining imperfections, as that can impact accuracy.

Does the slide shake laterally or front to back? With springs removed, will the barrel move back and forth when locked to the slide?

After shooting, it’s a good idea to check the firing pin and extractor for nicks or dings.

Triggernometry

Specifications will almost always tell you the pull weight, but that’s just part of the story. Trigger quality means everything. A superlative 7-lb. trigger can shoot better than a subpar 4.5-lb. one.

How does the “pull” feel? Any grit detectable through the finger? Some have a warm butter on warm butter take-up while others are brick on brick. How about the pressure stage? Overtravel? Does the trigger keep moving backward after the break? If so, is there an adjustment to minimize it? Next, very carefully maintaining strict muzzle discipline, I’ll listen to the trigger as it goes through the press and reset. Yep, with the muzzle pointed in a safe direction, I hold the gun right next to my ear and listen. What’s going on in there? Any grating? Some of our folks will don electronic ears to hear this better. Our significant others are accustomed to the weirdness.

And the break. Is it mushy or crisp or somewhere in between? I’ll try to describe that in words as best I can, along with distances for pre-travel, take-up to the break, and to the reset. Don’t tell anyone, but I measure these (approximately) with a wooden ruler. Hey, it works.

Shooting

Step one is to verify any safeties or decockers. Too many variations to go through here, so for starters, check the Jan/Feb 23 Insider to learn the process for 1911s. Also, verify the magazine safety if present.

Limp wristing malfunctions are (largely) preventable. Chalk them up to operator error. While I wouldn’t criticize a gun requiring a firm and solid grip, I do award extra points for those defensive handguns capable of forgiving function. Beretta 92s (and many others) can fire reliably when held loosely with a thumb and middle finger. If I’m ever shooting from a less-than-ideal position (off-hand, while fighting, injured, or whatever), I know the pistol is going to work sans a perfect grip.

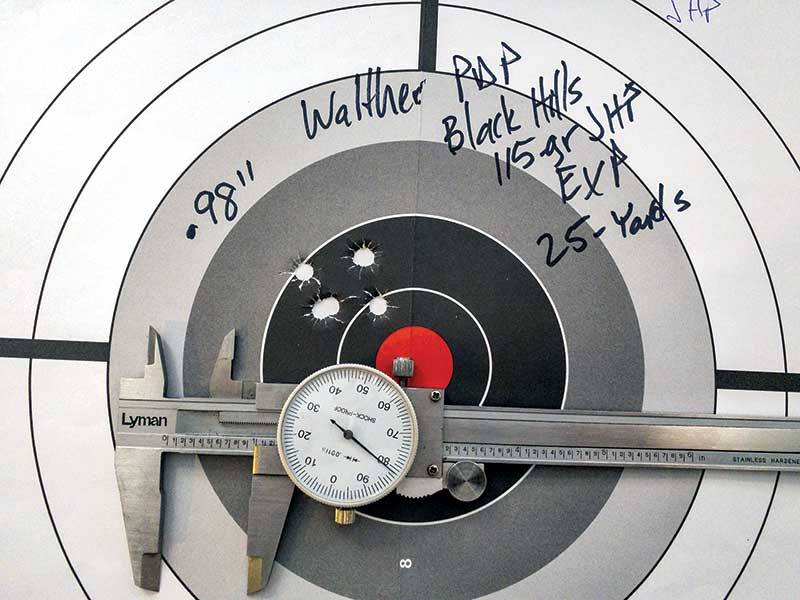

I prefer to shoot a new gun with a variety of ammo weights and bullet profiles, and I always test accuracy with every load available using 5-shot groups at 25 yards. FMJ, hollow points, lead when applicable and synthetic coated bullets offer insights into a gun’s feeding capability.

Checking the ejection pattern can indicate problems if it’s erratic or weak. I’ll also inspect ejected brass for unusual damage. Be sure to look at the primers too.

For carry or defense guns, I check how easily magazines drop, whether full or empty. I’m not interested in tugging out empties or bad ones.

While at the range, I’ll shoot a lot with topped-off “plus one in the chamber” configurations to see if the extra mag spring pressure impacts function.

It’s also a good idea to shoot normally and with the gun tilted left and right to make sure function isn’t impacted.

Accuracy

I have a pet peeve about gun ’riters claiming the “accuracy” of a pistol while shooting unsupported and peeping over the iron sights. That tells me how easy the gun is to shoot, how much coffee the shooter had, and how good their eyesight is. It doesn’t tell me jack about the mechanical accuracy of the gun.

For a true “what will this gun really do in perfect conditions” measurement, I’m going to a Ransom Multi-Caliber rest and eliminating all possible sighting imprecision from the scenario. Footnote: A machine rest would be better, but it gets impractical. That means using a handgun scope or at least a red dot. Sorry, but many modern guns are more accurate than our eyeballs at 25 yards. If said gun won’t take either, I stole a tip from Special Projects Editor Roy and use Mountain Plain Victory targets (PrecisionTargets.com).

While we’re testing accuracy, I like to observe point of impact relative to the sights, especially if the sights have limited adjustability like windage only.

There’s clearly much more to do, but this quick and dirty list covers most of the basics.